By Wayne Smith

They may not attract as much attention as last month’s daylight fireball over New York City, but stargazers can still anticipate seeing some shooting stars with the upcoming Perseid meteor shower. Caused by Earth passing through trails of debris left behind by Comet Swift-Tuttle, the shower has become famous over the centuries because of its consistent display of celestial fireworks.

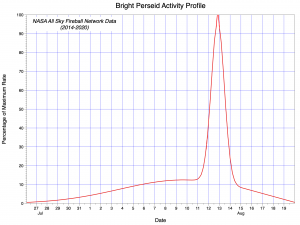

“The Perseids is the best annual meteor shower for the casual stargazer,” said Bill Cooke, who leads NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office at the agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “Not only is the shower rich in bright meteors and fireballs – No. 1 in fact – it also peaks in mid-August when the weather is still warm and comfortable. This year, the Perseid maximum will occur on the night of Aug. 11 and pre-dawn hours of Aug. 12. You’ll start seeing meteors from the shower around 11 p.m. local time and the rates will increase until dawn. If you miss the night of the 11th, you will also be able to see quite a few on the night of the 12th between those times.”

The best way to see the Perseids is to find the darkest possible sky and visit between midnight and dawn on the morning of Aug. 12. Allow about 45 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the dark. Lie on your back and look straight up. Avoid looking at cell phones or tablets because their bright screens ruin night vision and take your eyes off the sky.

Perseid meteors travel at the blistering speed of 132,000 mph – or 500 times faster than the fastest car in the world. At that speed, even a smidgen of dust makes a vivid streak of light when it collides with Earth’s atmosphere. Peak temperatures can exceed 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit as they speed across the sky. The Perseids pose no danger to people on the ground as practically all burn up 60 miles above our planet.

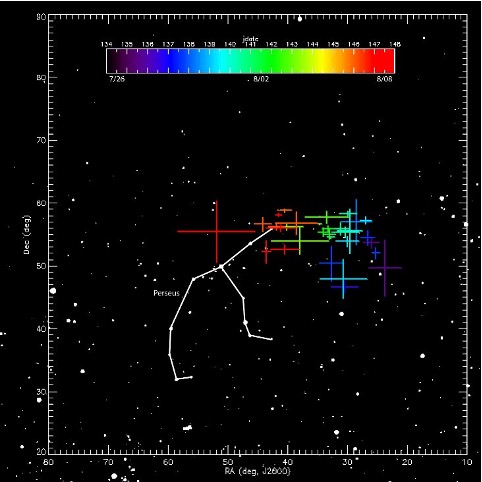

The first Perseid captured by NASA’s All Sky Meteor Camera Network was recorded at 9:48 p.m. EDT on July 23. The meteor – about as bright as the planet Jupiter, so not quite bright enough to be considered a fireball – was caused by a piece of Comet Swift-Tuttle about 5 millimeters in diameter entering the atmosphere over the Atlantic and burning up 66 miles above St. Cloud, Florida, just south of Orlando.

Rare Fireball in New York, New York Not Perseids

It wasn’t part of the Perseids, but a rare daylight fireball streaked across the sky over New York City at 11:15 a.m. EDT on Tuesday, July 16. The event gained national attention and was reported in media outlets across the U.S.

The fireball, defined as a meteor brighter than the planet Venus, is estimated to have soared over New York City before traversing a short path southwest and disintegrating about 31 miles above Mountainside, New Jersey. Cooke said the meteor was likely about 1 foot in diameter, which would have made the rock bright enough to see during the day. Seeing a meteor of this size is rarer than catching sight of the smaller particles a few millimeters in size typically seen in the night sky.

“To see one in the daytime over a populated area like New York is fairly rare,” Cooke said during an interview with ABC 7 in New York.

The Meteoroid Environments Office studies meteoroids in space so that NASA can protect our nation’s satellites, spacecraft and even astronauts aboard the International Space Station from these bits of tiny space debris.

For more skywatching highlights in April, check out Jet Propulsion Lab’s What’s Up series.

Lane Figueroa

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala.

256.544.0034

lane.e.figueroa@nasa.gov