by Ellen Gray / WALVIS BAY, NAMIBIA /

The ORACLES science team is in southern Africa to fly.

The bulk of their work is done in the narrow confines of the stocky P-3 aircraft amid racks of customized instruments. In the coming weeks these instruments will be complemented by remote sensors on the high-altitude ER-2 aircraft. But while the ER-2 team waits for the arrival of their specialized fuel, the science flight on September 2 is all P-3.

For this 8:00 a.m. flight, wake up time is early but you wouldn’t know it for the palpable sense of excitement the scientists have as they board the plane. This is the first “flight of opportunity;” the theme: It’s Positively Radiant Research. The flight will focus on the energy balance of the clouds over the ocean: how much light are clouds reflecting or absorbing as they interact with the smoke aerosols that travel from agricultural fires in central Africa.

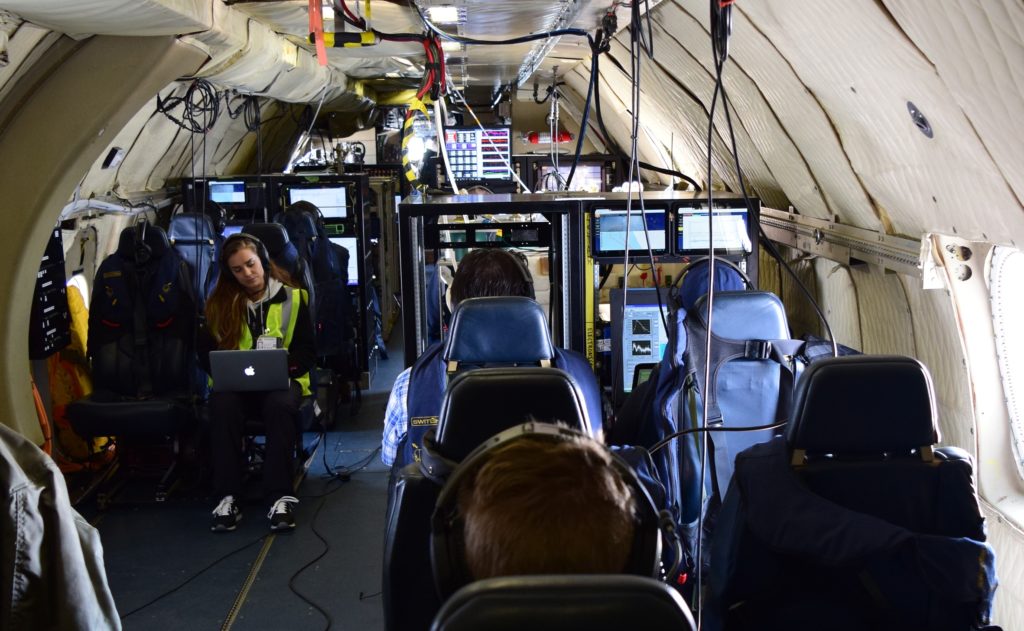

The inside of the P-3 looks like a laboratory with big boxy instruments in front of airline seats. Twenty-four scientists can fly at a time with more than a dozen instruments. Once everyone’s aboard, ears safely covered by noise-cancelling headphones, the turboprop engines fire up. The P-3 taxis down the runway and takes off.

This is a LOUD plane – deafening, in fact. The headsets have the dual role of hearing protection and allowing everyone on board to communicate, reporting real-time observations. Sebastian Schmidt of the University of Colorado, Boulder is the flight scientist today. Sitting up front, his is the single voice speaking to the pilots, relaying any requests for adjustments in the flight path that come from the instrument teams.

The pilots, Mike Singer and Mark Russell of NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility, have final say on the flight path. They are responsible for the safety of the plane and its occupants. With hundreds of science flight hours under their belts, they’re very familiar with how scientists like to fly. Today it’s in tight spirals from the top of the smoke layer and clouds to near the ocean surface to see what the air is doing along a vertical column.

On this eight-hour flight, though, the science team channel isn’t all business. “Who still needs a nickname?” Sam LeBlanc of NASA’s Ames Research Center in charge of the 4STAR instrument asked at one point.

A number of the flying scientists apparently still do. Among them, Sabrina Cochrane, a second-year grad student at the University of Colorado, Boulder, manning the Solar Spectral Flux Radiometer. This is her first research flight.

“I was really nervous,” she said after the flight. “I thought I was going to feel sick the whole time with all the spirals, but I didn’t. It was really smooth. It was a lot more fun than I expected.”

Flying between the spiral locations, the Airborne Precipitation Radar team was on the look-out for another high-flyer: the CloudSat satellite in space, which was scheduled to make a pass over the same region the P-3 was flying. This radar measures cloud droplet sizes and numbers, validating the same measurements taken from space by CloudSat’s radar.

The satellite overpass was not exactly over the flight path, but close enough, said Steve Durden of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Even if they’re not perfectly aligned you’ll see the same structures in the clouds,” he said.

The final maneuvers of the day occur during the last hour of flight on the way back to Walvis Bay Airport. David Noone of Oregon State University explained that these maneuvers are for the instruments, to find out how different orientations of the aircraft affect the measurements.

“My measurements, the water vapor and the water vapor isotope measurements, are a good example of this. We’re bringing in air from outside through an inlet that must be pointing directly forward into the flow. If it’s slightly off, the number of cloud droplets that enter the inlet might vary,” he said.

To test out the orientations the pilots will wiggle the tail of the aircraft, roll side to side, and go up and down like they’re going over a hill.

“Now some of these are good fun,” said Noone, “but we’re sitting here in the back of the aircraft. We’re way out in the tail so we’re going to get a good ride.”