by Kate Ramsayer / THE SKIES ABOVE ANTARCTICA /

The crack that would become B-46 was first noticed in September 2018 – and the berg broke the next month.

NASA’s Operation IceBridge flew over a new iceberg that is three times the size of Manhattan on Wednesday – the first known time anyone has laid eyes on the giant berg, dubbed B-46, that broke off from Pine Island Glacier in late October.

The flight over one of the fastest-retreating glaciers in Antarctica was part of IceBridge’s campaign to collect measurements of Earth’s changing polar regions. Surveys of Pine Island are one of the highest priority missions for IceBridge, in part because of the glacier’s significant impact on sea level rise.

On Wednesday, IceBridge’s approach to the iceberg began far above the glacier’s outlet, in the upper reaches of ice that will eventually flow into the glacier’s trunk. There, as far as the eye can see, it was flat and it was white.

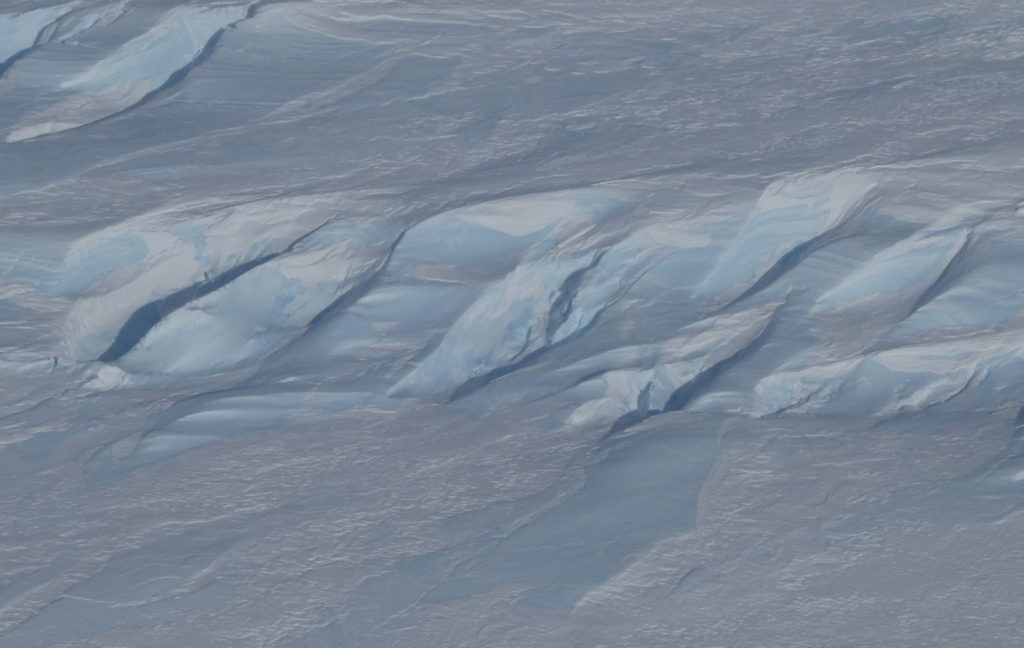

As the aircraft headed toward the glacier’s outlet in the Amundsen Sea, snow-covered crevasses became visible when sunlight struck at just the right angle. Every once in a while, a dark hole appeared in the crevasses where the snow had fallen through, providing a glimpse into the depths of the ice sheet. Then the holes got bigger.

The crevasses and dunes became a jumbled mess of ice, as Pine Island Glacier picks up speed as it flows to the sea. The crevasses got deeper and wider, swirling around each other. Striated snow layers in white and pale blue were visible down the crevasse walls, like an icy version of the slot canyons in the American West.

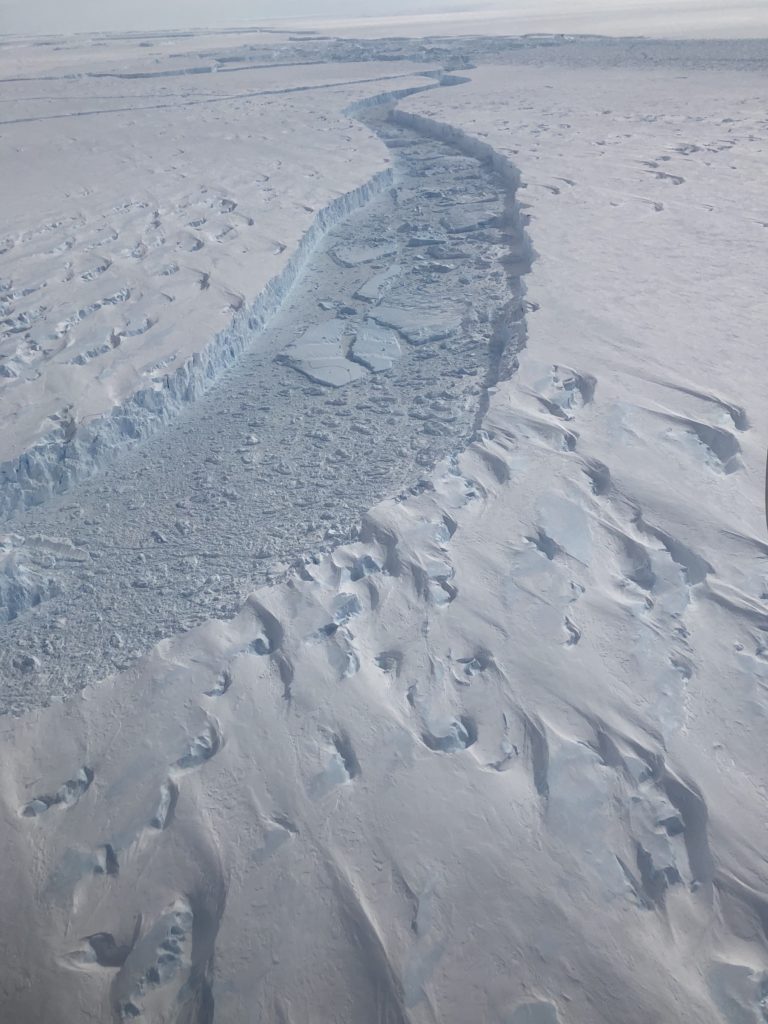

Then finally – the berg. Satellite imagery had revealed a massive calving event from Pine Island in late October, and the IceBridge crew was the first to lay eyes on the newly created iceberg.

The glacier ends in a sheer 60-meter cliff, dropping off into an ocean channel filled with a mix of bergy bits, snow, and newly forming sea ice. On the other side, a matching jagged cliff marked the beginning of B-46, as it stretched across the horizon.

“From this perspective at 1,500 feet, it’s actually really difficult to grasp the entire scale of what we just looked at,” said Brooke Medley, Operation IceBridge’s deputy project scientist who has studied Pine Island Glacier for 12 years. “It was absolutely stunning. It was spectacular and inspiring and humbling at the same time.”

Even though it had calved just over a week ago, the berg was already showing signs of wear and tear. Cracks wove through B-46, and upturned bergy bits floated in wide rifts. The iceberg will probably break down into smaller icebergs within a month or two, Medley said.

Iceberg calving is normal for glaciers – snow falls within the glacier’s catchment and slowly flows down into the main trunk, where the ice starts to flow faster. Eventually it encounters the ocean, is lifted afloat, and over time travels to the edge of the shelf. There, ice breaks off in the form of an iceberg. When the amount of snowfall and ice loss (from iceberg calving and melt) are the same, a glacier’s in balance. So it’s hard to link a particular iceberg like B-46 to the increasing ice loss from Pine Island Glacier.

But the frequency, speed, and size of the calving is something to keep an eye on, Medley said. In 2016, IceBridge saw a crack beginning across the base of Pine Island; it took a year for an actual rift to form and the iceberg to float away.

The crack that would become B-46 was first noticed in September 2018 – and the berg broke the next month.

They’re not the biggest glaciers on the planet, but Pine Island and its neighbor, Thwaites, have an oversized impact on sea level rise. Enough ice flows from each of these West Antarctic glaciers to raise sea levels by more than 1 millimeter per decade, according to a study led by Medley. And by the end of this century, that number is projected to at least triple.

“It’s deeply concerning,” Medley said. The geography of these glaciers make them highly susceptible to ice loss: relatively warm waters cut under the ice shelf, weakening it from below. This shock to the system has the capability to initiate an unstoppable retreat of these glaciers. There’s a reason Pine Island and Thwaites are dubbed the “weak underbelly” of Antarctica.

NASA has been monitoring Pine Island Glacier from aircraft since 2002, and IceBridge started taking extensive measurements of the fast-moving ice in 2009.

“Both Pine Island and Thwaites are ready to go and to take their neighboring glaciers with them,” Medley said. “Ice is getting sucked out into the ocean – and it’s hard to stop it.”