Have questions about solar flares? Find answers here!

What is a solar flare?

A solar flare is an intense burst of radiation, or light, on the Sun. Flares are our solar system’s most powerful explosive events – the most powerful flares have the energy equivalent of a billion hydrogen bombs, enough energy to power the whole world for 20,000 years.

Light only takes about 8 minutes to travel from the Sun to Earth, so that’s how long it would take the energy from a flare to reach our planet.

How do solar flares affect Earth?

Solar flares only affect Earth when they occur on the side of the Sun facing Earth. Solar flares are rated into different classes based on their strength, or energy output, and the effect a flare will have on Earth depends on what class it is (B, C, M, and X classes, with X being the most intense). Learn more about flare classes here:

Earth’s atmosphere absorbs most of the Sun’s intense radiation, so flares are not directly harmful to humans on the ground. However, the radiation from a flare can be harmful to astronauts outside of Earth’s atmosphere, and they can affect the technology we rely on.

Stronger solar flares – those rated class M5 or above – can have impacts on technology that depends on Earth’s ionosphere, our electrically charged upper atmosphere, like high-frequency radio used for navigation and GPS. When the burst of light from a flare reaches Earth, it can cause surges of electricity and scintillation, or flashes of light, in the ionosphere, leading to radio signal blackouts that can last for minutes or, in the worst cases, hours at a time. One risk of a radio blackout is that radios are often used for emergency communications, for instance, to direct people amid an earthquake or hurricane.

What is the difference between a solar flare and a coronal mass ejection (CME)?

Solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) both involve gigantic explosions of energy, but are otherwise quite different. Solar flares are bright flashes of light, whereas CMEs are giant clouds of plasma and magnetic field. The two phenomena do sometimes occur at the same time – indeed the strongest flares are almost always correlated with coronal mass ejections – but they emit different things, they look and travel differently, and they have different effects near planets.

Here’s more on the difference between a solar flare and a CME:

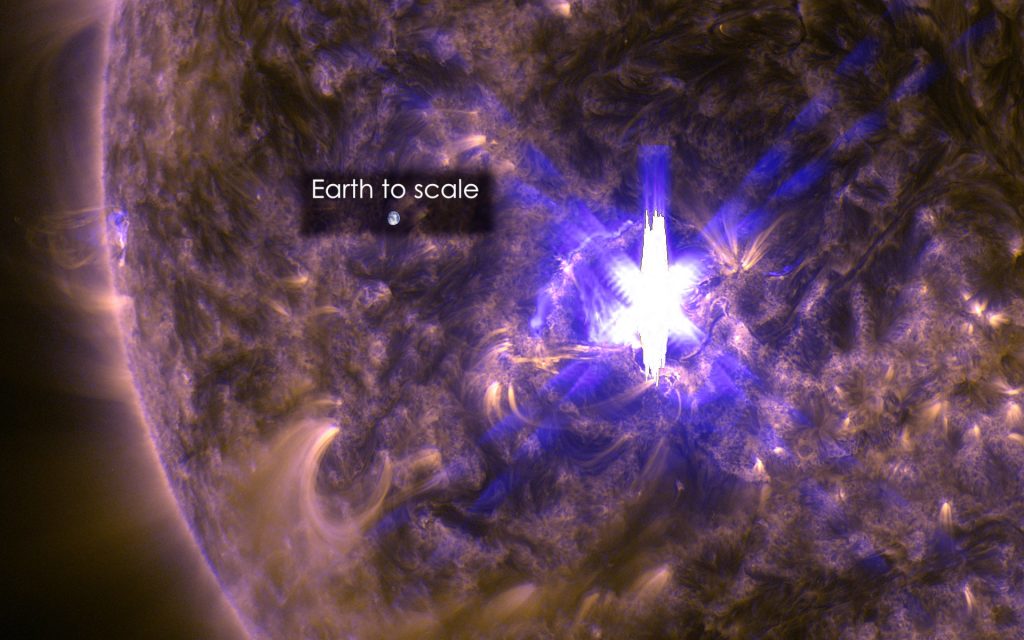

How big are solar flares?

Flares tend to come from active regions on the Sun several times the size of Earth or more.

Credits: NASA/SDO

How long do solar flares last?

Solar flares can last from minutes to hours. Sometimes the same active region on the Sun can give rise to several flares in succession, erupting over the course of days or even weeks.

What causes solar flares?

Solar flares erupt from active regions on the Sun – places where the Sun’s magnetic field is especially strong and turbulent. Active regions are formed by the motion of the Sun’s interior, which contorts its own magnetic fields. Eventually, these magnetic fields build up tension and explosively realign, like the sudden release of a twisted rubber band, in a process known as magnetic reconnection. This rapid energy transfer creates solar flares as well as other kinds of solar eruptions like coronal mass ejections and solar energetic particle events.

Do flares occur on other stars?

Yes! Flares occur on most if not all types of stars (although in that case they’re called “stellar” rather than “solar” flares). In fact, flares from other stars are frequently more severe – both stronger and more frequent – than those produced by the Sun.

How often do solar flares occur?

Like earthquakes, the frequency of solar flares depends on their size, with small ones erupting more often than big ones. The number of flares also increases as the Sun nears solar maximum, and decreases as the Sun nears solar minimum. So, throughout the 11-year solar cycle, flares may occur several times a day or only a few times per month.

How do we study solar flares?

We study flares by detecting the light they emit. Flares emit visible light but they also emit at almost every wavelength of the electromagnetic spectrum. Flares also shoot out particles (electrons, protons, and heavier particles) that spacecraft can detect.

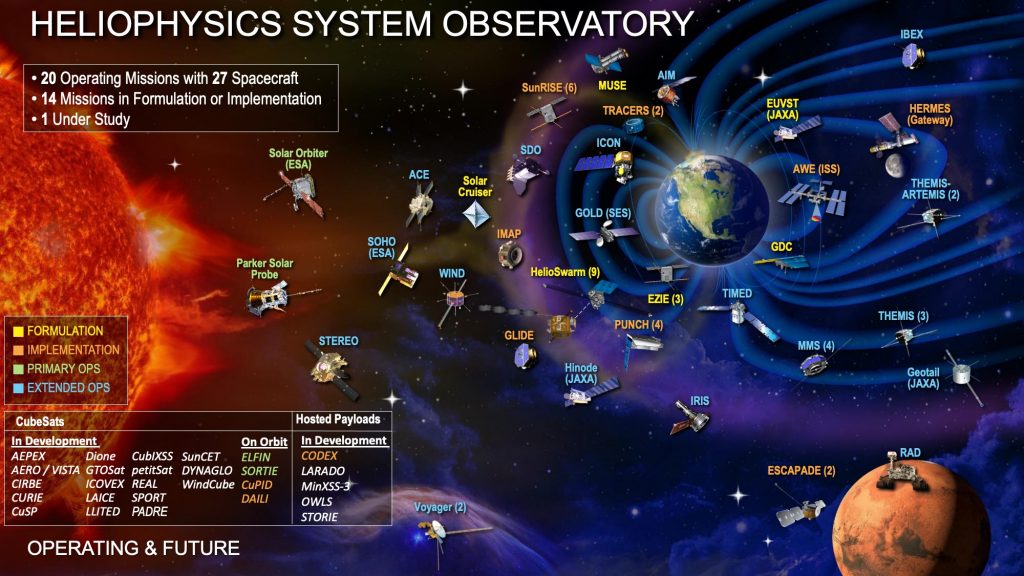

Scientists used ground- and space-based sensors and imaging systems to study flares. NASA operates a suite of Heliophysics missions, utilizing its entire fleet of solar, heliospheric, and geospace spacecraft to discover the processes at work throughout the space environment.

NASA also works with other agencies to study and coordinate space weather activities. The Committee on Space Weather, which is hosted by the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology, is a multiagency organization co-chaired by representatives from NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the United States Department of Defense, and the National Science Foundation and functions as a steering group responsible for tracking the progress of the National Space Weather Program.

Can we predict when a solar flare will occur?

We cannot yet predict when a specific solar flare will occur, but we can measure several factors that make a flare more likely to occur. Flares erupt from active regions, where the Sun’s magnetic field becomes especially intense, so we monitor the Sun’s magnetic activity and when an active region forms, we know a flare is more likely. On longer timescales, the Sun goes through periodic variations or cycles of high and low activity that repeat approximately every 11 years, known as the solar cycle. Solar minimum refers to the period when the number of sunspots is lowest and solar activity, including flares, is lower; solar maximum occurs in the years when sunspots are most numerous and flares are more common.

Who is responsible for tracking and sending alerts when there is solar activity

NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) is the nation’s official source of space weather alerts, watches, and warnings. It provides real-time monitoring and forecasting of solar and geophysical events. SWPC is part of the National Weather Service and is one of the nine National Centers for Environmental Prediction.

By Miles Hatfield

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.