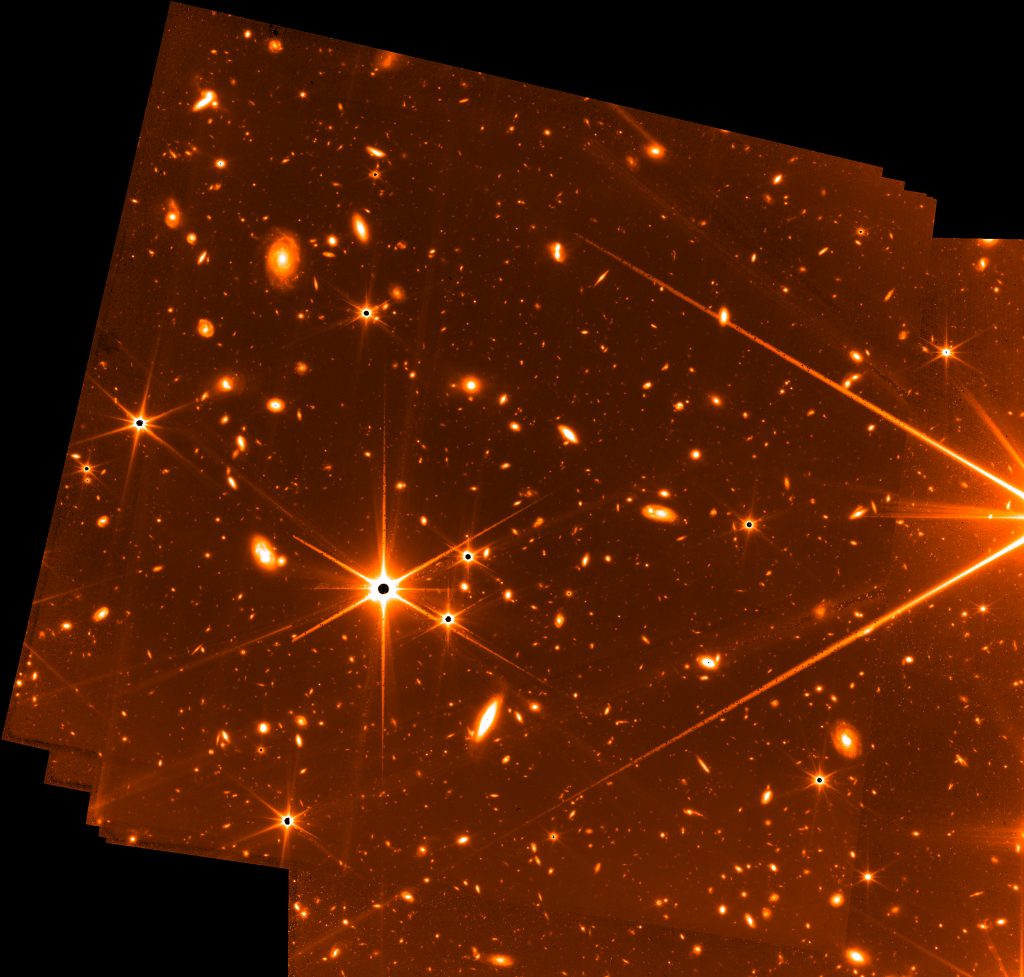

People around the world joined together in excitement as the first color scientific images and spectra from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope were revealed this week. Webb is fully commissioned and already embarked on its first year of peer-reviewed science programs. We asked Webb senior project scientist John Mather to reflect on reaching this moment after 25 years, taking Webb from an initial spark of an idea to the world’s premier space observatory.

“It was worth the wait! Our immense golden telescope is seeing where none have seen before, discovering what we never knew before, and we are proud of what we have done. It’s our day to thank the people who made it possible, from the scientific visionaries in 1989 and 1995, to the 20,000 engineers, technicians, computer programmers, and scientists who did the work, and to the representatives of the people in the U.S., Europe, and Canada, who had faith in us and supported us. And special thanks to Senator Barbara Mikulski, who saved not one but two telescopes, with her inspiration and determination that setbacks are never the end. And special thanks to Goddard Project Manager Bill Ochs and Northrop Grumman Project Manager Scott Willoughby, who together pulled us all through every challenge to complete success.

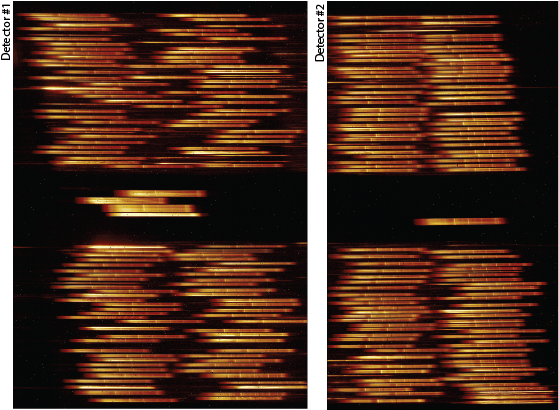

“Already we have stood on the shoulders of giants like the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes, and seen farther. We have seen distant galaxies, as they were when the universe was less than a billion years old, and we’re just beginning the search. We have seen galaxies colliding and merging, revealing their chemical secrets. We have seen one black hole close up, in the nucleus of a nearby galaxy, and measured the material escaping from it. We’ve seen the debris when a star exploded, liberating the chemical elements that will build the next generations of stars and planets. We have started a search for Earth 2.0, by watching a planet transiting in front of its star, and measuring the molecules in its atmosphere.

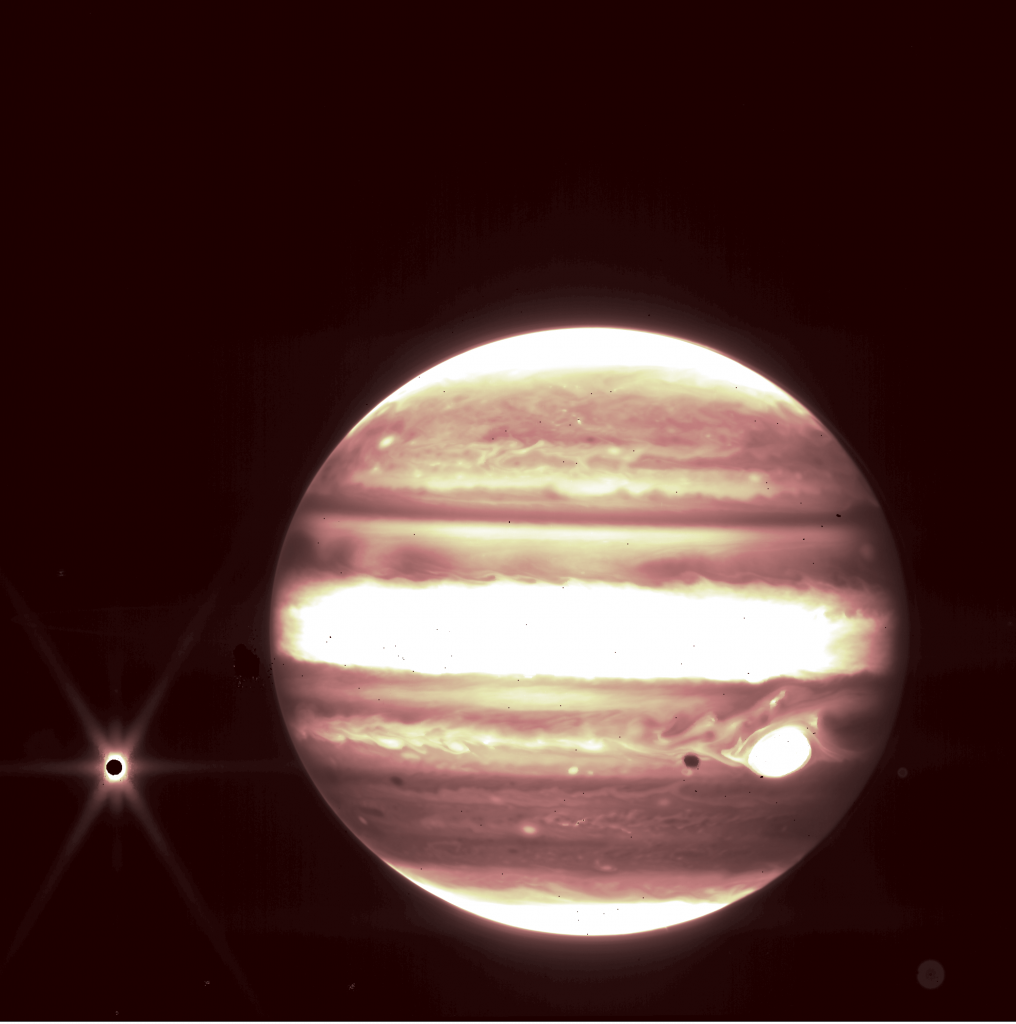

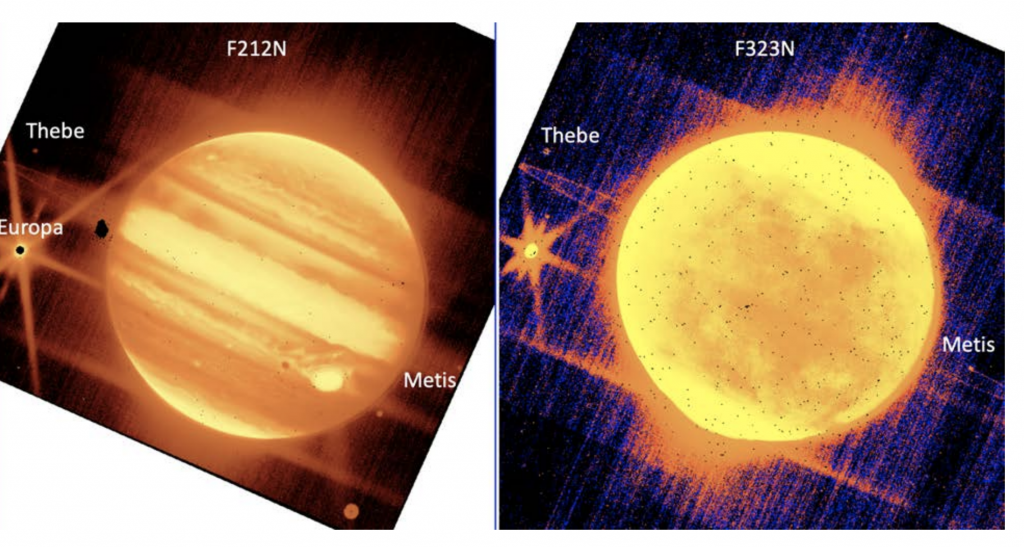

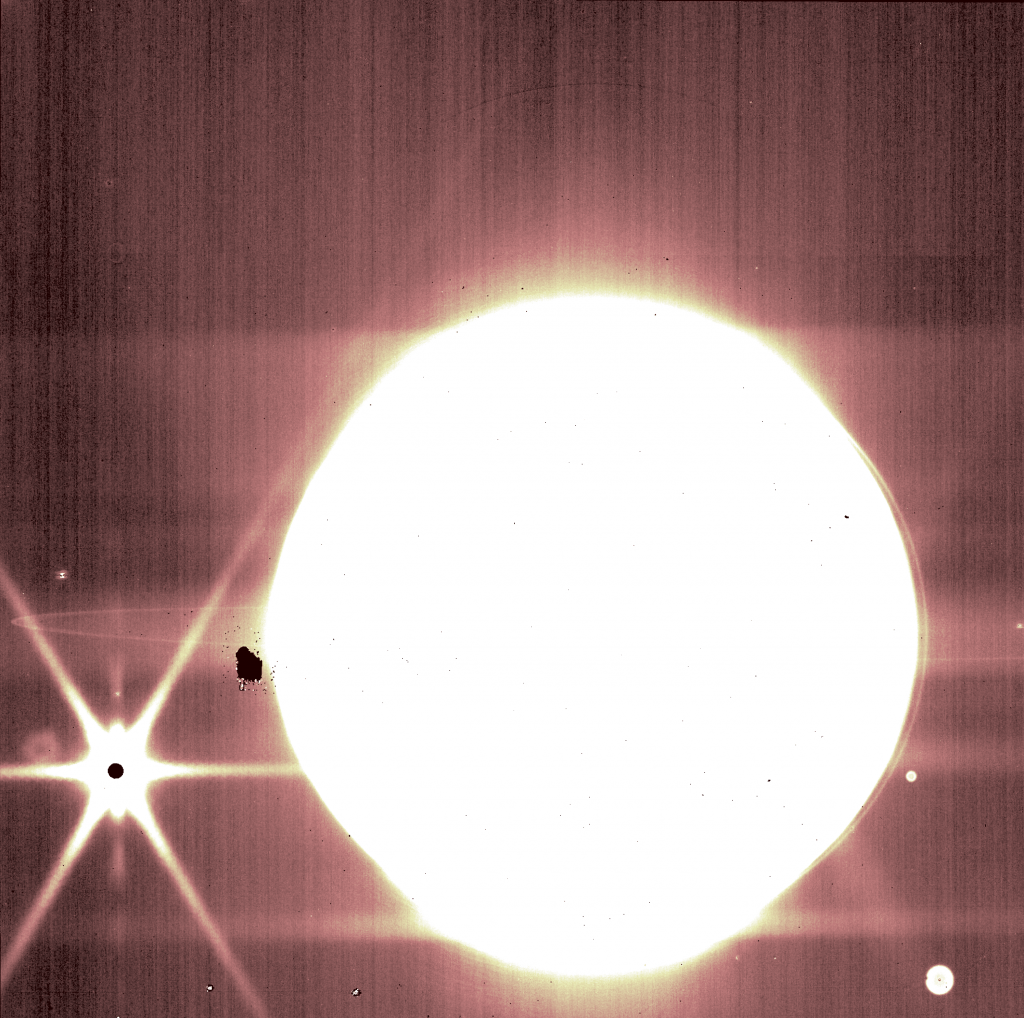

“What comes next? All the tools are working, better than we hoped and promised. Scientific observations, proposed years ago, are being made as we speak. We want to know: Where did we come from? What happened after the big bang to make galaxies and stars and black holes? We have predictions and guesses, but astronomy is an observational science, full of surprises. What are the dark matter and dark energy doing? How do stars and planets grow inside those beautiful clouds of gas and dust? Do the rocky planets we can observe with Webb have any atmosphere at all, and is there water there? Are there any planetary systems like our solar system? So far we have found exactly none. We’ll look at our own solar system with new infrared eyes, looking for chemical traces of our history, and tracking down mysteries like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, composition of the ocean under the ice of Europa, and the atmosphere of Saturn’s giant moon Titan. We’ll be ready to study the next interstellar comet.

“With the precise launch on Christmas morning 2021, we look forward to 20 years of operation before we run out of propellant. Though we suffer the pings of tiny micrometeoroids, so tiny you couldn’t feel one if you had it in your fingers, we think the telescope can meet its original performance likely long beyond its five-year design life. In 2027 we will launch the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which will scan vast areas of the sky for new fascinating targets for Webb, while also hunting for the effects of dark matter and dark energy. We know the Webb images will rewrite our textbooks, and we hope for a new discovery, something so important that our view of the universe will be overturned once again.

Webb was worth the wait!”

– John Mather, Webb senior project scientist, NASA Goddard