Author: Karen Fox

Webb Team Tensions Fifth Layer, Sunshield Fully Deployed

At approximately 11:59 am EST, the fifth and final layer of Webb’s sunshield was fully tensioned, marking the completion of sunshield deployment. Read more about this key milestone in preparing Webb for science operations.

Tensioning Begins for Two Layers of Webb’s Sunshield

With three layers of Webb’s sunshield fully deployed, the team commenced tensioning – that is, pulling each layer fully taut – of the final two layers this morning.

We will have live coverage of the fifth layer tensioning at nasa.gov/live beginning at about 9:30 am EST.

First Layer of Webb’s Sunshield Tightened

Today, at 3:48 pm EST, the Webb team finished tensioning the first layer of the observatory’s sunshield– that is, tightening it into its final, completely taut position. This is the first of five layers that will each be tightened in turn over the next two to three days, until the observatory’s sunshield is fully deployed. The process began around 10 am EST.

This layer is the largest of the five, and the one that will experience the brunt of the heat from the Sun. The tennis-court-sized sunshield helps keep the telescope cold enough to detect the infrared light it was built to observe.

The team has now begun tensioning the second layer.

NASA Says Webb’s Excess Fuel Likely to Extend its Lifetime Expectations

After a successful launch of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope Dec. 25, and completion of two mid-course correction maneuvers, the Webb team has analyzed its initial trajectory and determined the observatory should have enough propellant to allow support of science operations in orbit for significantly more than a 10-year science lifetime. (The minimum baseline for the mission is five years.)

The analysis shows that less propellant than originally planned for is needed to correct Webb’s trajectory toward its final orbit around the second Lagrange point known as L2, a point of gravitational balance on the far side of Earth away from the Sun. Consequently, Webb will have much more than the baseline estimate of propellant – though many factors could ultimately affect Webb’s duration of operation.

Webb has rocket propellant onboard not only for midcourse correction and insertion into orbit around L2, but also for necessary functions during the life of the mission, including “station keeping” maneuvers – small thruster burns to adjust Webb’s orbit — as well as what’s known as momentum management, which maintains Webb’s orientation in space.

The extra propellant is largely due to the precision of the Arianespace Ariane 5 launch, which exceeded the requirements needed to put Webb on the right path, as well as the precision of the first mid-course correction maneuver – a relatively small, 65-minute burn after launch that added approximately 45 mph (20 meters/sec) to the observatory’s speed. A second correction maneuver occurred on Dec. 27, adding around 6.3 mph (2.8 meters/sec) to the speed.

The accuracy of the launch trajectory had another result: the timing of the solar array deployment. That deployment was executed automatically after separation from the Ariane 5 based on a stored command to deploy either when Webb reached a certain attitude toward the Sun ideal for capturing sunlight to power the observatory – or automatically at 33 minutes after launch. Because Webb was already in the correct attitude after separation from the Ariane 5 second stage, the solar array was able to deploy about a minute and a half after separation, approximately 29 minutes after launch.

From here on, all deployments are human-controlled so deployment timing – or even their order — may change. Explore what’s planned here.

Webb’s Second Mid-Course Correction Burn

At 7:20 pm EST – 60 hours after liftoff — Webb’s second mid-course correction burn began. It lasted 9 minutes and 27 seconds and is now complete. This burn is one of three planned course corrections to put the telescope precisely in orbit around the second Lagrange point, commonly known as L2.

More Details on Webb’s Launch

While the team continues to work on unfolding Webb, we take a moment to learn more about the launch from two European Space Agency (ESA) representatives, Daniel de Chambure, Acting Head Ariane 5 Adaptation & Future Missions for ESA and Maurice Te Plate, JWST NIRSpec Systems and AIV Engineer for ESA. They provide details about the launch trajectory, which is the first phase of Webb’s journey before additional planned course corrections:

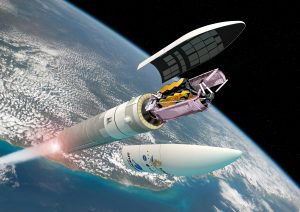

Europe’s Ariane 5 delivered Webb, with a launch mass of about 13,700 lbs (6200 kg), into the first phase of its planned trajectory toward its final position orbiting the L2 Lagrange point. As we all held our collective breath, lift-off was on December 25, 2021 at 7:20 am EST from Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, for a flight lasting about 27 minutes before spacecraft separation.

About seven seconds after start of the ignition of the main stage cryogenic engine, the two solid propellant boosters were ignited, enabling liftoff. The launcher first climbed vertically for about 13 seconds, and then rotated towards the East. The solid boosters were jettisoned 2 mins and 14 sec after liftoff.

The fairing that protected Webb from the acoustic, thermal and aerodynamic stresses during the ascent, was jettisoned 3 minutes and 19 sec after liftoff. In order to protect the delicate thermal sunshield blankets of Webb, the fairing had been modified to minimize the shock of depressurization at separation. Updated venting ports allowed the pressure inside the fairing to properly equalize prior to opening. The recorded residual pressure was successfully below the required allowed maximum.

Once the atmospheric part of the flight was completed, Ariane’s onboard computers optimized the trajectory in real time, and brought the launcher to the intermediate orbit targeted at the end of the main stage propulsion phase, at 8 minutes and 35 seconds after launch. Ten seconds later, the HM7B engine of the cryogenic upper stage, with Webb still on top, was ignited and operated for a duration of 16 minutes. After engine shut-down, the upper stage underwent a number of positioning maneuvers with its attitude control system in order to separate Webb at the required attitude.

After separation, the upper stage underwent a delicate series of contamination and collision avoidance maneuvers, making sure that its thruster plumes did not impinge on Webb and its precious optics.

Finally, an end-of-life maneuver was performed to avoid potential long term collision risks with Webb.

Webb had started its journey to explore the Universe. Webb is on its way!

-Daniel de Chambure, Acting Head Ariane 5 Adaptation & Future Missions, ESA

-Maurice Te Plate, JWST NIRSpec Systems and AIV Engineer, ESA

More Than You Wanted to Know About Webb’s Mid-Course Corrections!

On Dec. 25, the Webb team successfully executed the first of three planned orbit corrections to get Webb into its halo orbit around the second Lagrange point, L2. To hear more about these important maneuvers, here is Randy Kimble, the Webb Integration, Test, and Commissioning Project Scientist, at NASA Goddard:

In sending the Webb Observatory into its orbit around the Sun-Earth L2 point, the vast majority of the energy required was provided by the Ariane 5 rocket. After release of the observatory from the rocket, several small tweaks to the trajectory are planned, to ease the observatory into its operating orbit about one month after launch.

The largest and most important mid-course correction (MCC), designated MCC-1a, has already been successfully executed as planned, beginning 12.5 hours after launch. This time was chosen because the earlier the course correction is made, the less propellant it requires. This leaves as much remaining fuel as possible for Webb’s ordinary operations over its lifetime: station-keeping (small adjustments to keep Webb in its desired orbit) and momentum unloading (to counteract the effects of solar radiation pressure on the huge sunshield).

The burn wasn’t scheduled immediately after launch to give time for the flight dynamics team to receive tracking data from three ground stations, widely separated over the surface of the Earth, thus providing high accuracy for their determination of Webb’s position and velocity, necessary to determine the precise parameters for the correction burn. Ground stations in Malindi Kenya, Canberra Australia, and Madrid Spain provided the necessary ranging data. There was also time to do a test firing of the required thruster before executing the actual burn. We are currently doing the analysis to determine just how much more correction of Webb’s trajectory will be needed, and how much fuel will be left, but we already know that the Ariane 5’s placement of Webb was better than requirements.

One interesting aspect of the Webb launch and the Mid-Course Corrections is that we always “aim a little bit low.” The L2 point and Webb’s loose orbit around it are only semi-stable. In the radial direction (along the Sun-Earth line), there is an equilibrium point where in principle it would take no thrust to remain in position; however, that point is not stable. If Webb drifted a little bit toward Earth, it would continue (in the absence of corrective thrust) to drift ever closer; if it drifted a little bit away from Earth, it would continue to drift farther away. Webb has thrusters only on the warm, Sun-facing side of the observatory. We would not want the hot thrusters to contaminate the cold side of the observatory with unwanted heat or with rocket exhaust that could condense on the cold optics. This means the thrusters can only push Webb away from the Sun, not back toward the Sun (and Earth). We thus design the launch insertion and the MCCs to always keep us on the uphill side of the gravitational potential, we never want to go over the crest – and drift away downhill on the other side, with no ability to come back.

Therefore, the Ariane 5 launch insertion was intentionally designed to leave some velocity in the anti-Sun direction to be provided by the payload. MCC-1a similarly was executed to take out most, but not all, of the total required correction (to be sure that this burn also would not overshoot). In the same way, MCC-1b, scheduled for 2.5 days after launch, and MCC-2, scheduled for about 29 days after launch (but neither time-critical), and the station-keeping burns throughout the mission lifetime will always thrust just enough to leave us a little bit shy of the crest. We want Sisyphus to keep rolling this rock up the gentle slope near the top of the hill – we never want it to roll over the crest and get away from him. The Webb team’s job, guided by the Flight Dynamics Facility at NASA Goddard, is to make sure it doesn’t.

-Randy Kimble, JWST Integration, Test, and Commissioning Project Scientist, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Webb Antenna Released and Tested

Shortly after 10 am EST on Dec. 26, the Webb team began the process of releasing the gimbaled antenna assembly, or GAA, which includes Webb’s high-data-rate dish antenna. This antenna will be used to send at least 28.6 Gbytes of science data down from the observatory, twice a day. The team has now released and tested the motion of the antenna assembly — the entire process took about one hour.

Separately, overnight, the temperature sensors and strain gauges on the telescope were activated for the first time. Temperature and strain data are now available to engineers monitoring Webb’s thermal and structural systems.

The First Mid-Course Correction Burn

At 7:50 pm EST, Webb’s first mid-course correction burn began. It lasted 65 minutes and is now complete. This burn is one of two milestones that are time critical — the first was the solar array deployment, which happened shortly after launch.

This burn adjusts Webb’s trajectory toward the second Lagrange point, commonly known as L2. After launch, Webb needs to make its own mid-course thrust correction maneuvers to get to its orbit. This is by design: Webb received an intentional slight under-burn from the Ariane-5 that launched it into space, because it’s not possible to correct for overthrust. If Webb gets too much thrust, it can’t turn around to move back toward Earth because that would directly expose its telescope optics and structure to the Sun, overheating them and aborting the science mission before it can even begin.

Therefore, we ease up to the correct velocity in three stages, being careful never to deliver too much thrust — there will be three mid-course correction maneuvers in total.

After this burn, no key milestones are time critical, so the order, location, timing, and duration of deployments may change.

You can track where Webb is in the process and read about upcoming deployments. NASA has a detailed plan to deploy the Webb Space Telescope over a roughly two-week period.The deployment process is not an automatic hands-off sequence; it is human-controlled. The team monitors Webb in real-time and may pause the nominal deployment at any time. This means that the deployments may not occur exactly in the order or at the times originally planned.