Could the lack of one thing make this Hubble repair mission impossible? Kaput, never to be? All that would remain for us is a deep sigh and a heartfelt wish to see more beautiful, yet unattainable, pictures of stellar nurseries and sudden, cataclysmic stellar deaths, extra-solar planetary atmospheres, and an exploration of dark energy, the mysterious force pulling our universe apart. Discoveries that would forever change how we see ourselves and our universe now wouldn’t be made. What intense problem would bring work on this last repair mission to a standstill? Politics? Inter-NASA Space Flight Center squabbling? A sudden need for swollen bags of money in a time of national crisis? Additional visits from FBI agents intent on reviewing minutiae while frightening young interns?

None of these answers even come close. Instead of rounding up the usual suspects, we humans must first come to grips with the reality of outer space. We want to conquer new worlds, to expand our sphere of influence and accomplishment, moving ever wider into our environment as victors in our solar system. Yet this homocentric universe view doesn’t even succeed in our nearest neighborhood, low-earth orbit, where we have placed Hubble. We humans are incapable of executing the intricate surgical repair plan for Hubble without serious outside help – robotic help.

Humans have visited Hubble four other times. During these visits to our on-orbit patient, internal surgery was only timidly attempted once. That’s when astronauts John Grunsfeld and Richard Linnehan successfully replaced the power switching station and its rat’s nest of cabling and connectors on Hubble in March 2002.

Major surgery is now required on patient Hubble. For the first time ever, we need to probe the guts inside in order to improve our patient’s remaining, productive days. One of those early surgeons, John Grunsfeld, will be returning to Hubble to perform this more invasive surgery.

The two instruments being cracked open on repair mission 4 are not designed for on-orbit repair. Back in the 1970’s and 80’s, we just couldn’t conceive of astronauts performing even minor internal surgery, so we didn’t build in the capability. In the relentless and unforgiving vacuum of space, human beings alone are just not up to the task, so it didn’t seem possible.

|

|

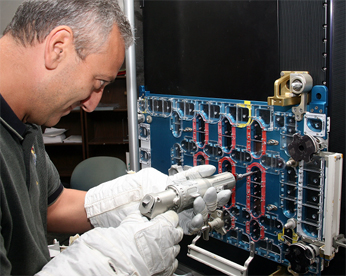

A technician tests the new mini-tool with the new

capture plate on the screws in the mock-up of the

Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS).

|

But we can do it with a partner, a marriage of convenience perhaps, but one which comes to the rescue. Robotic tools, fifty new ones to be exact. Although we’ve used tools before, advances in these fifty new tools are akin to advances from an 18th century barber-butcher-surgeon to our 21st century neurosurgeon.

The human being-robotic relationship (or being-roBots – – BBots for short) we are entering is akin to the beneficial symbiotic relationships commonly found among species on our Earth. Beneficial symbiotic relationships are ones in which plants or animals of different species depend on one another for survival. For instance, snapping shrimp and gobies live together in the same burrow on the ocean floor. The blind shrimp rely on the goby’s intruder warning alert to keep them safe, while the shrimp keep the burrow clean of parasites. There are thousands of other examples to be found on Earth.

|

|

The Yellow Clown Gobi and shrimp help each other

in their shared burrow.

|

In the case of Hubble, let’s see why the on-orbit repairs require a similar symbiotic relationship between the astronauts and the robotic tools. Let’s say you have a spectrograph on your lab bench. It is used to split light into all the colors of the rainbow for you, revealing information about its origin, temperature, and chemical makeup.

Now, you’re technically savvy, so you’ve discovered that one printed circuit board within your spectrometer contains a faulty power supply unit, making your beautiful spectrometer dead as a door nail. To add to your task, you have a second instrument on your bench, a camera, and it, too, has a failed power supply unit on one PCB. What would you do? Well, you’d just fix it, right? You’d simply open up the instruments, pull out the faulty boards, replace them with good boards, and put the instrument back together. Easy.

But now things get hairy. Your two instruments are placed in the deep end of a pool. And for the first time ever, these instruments are not designed for you to easily open them and get to the faulty cards while you and they are submersed in water.

So, you’re suited up in scuba gear and dumped into the deep end of the pool in order to perform these tasks under variable lighting, going from adequate to hazy. Oh, and of course you don’t want any of the 143 screws you’ve removed from these two instruments to float away. And you wouldn’t really want to put all those screws back in as you closed the two instruments up. As a diver, I know what would happen to me. With all these obstacles and things to think about, I might suck down all the air in my scuba tank!

Now would be the perfect time to reject the folly of a human being-robot competition and embrace the need for a cooperative marriage, if not from love, then from convenience.

Next week I’ll talk to the tool-master at Goddard, Justin Cassidy. He’ll reveal his favorite tools of all time for the Hubble repair mission.

What next? As Mr. Mordecai Albert says on his August 3rd comment, we all thirst for additional information on Hubble’s contributions to our knowledge of the cosmos.

So my follow-on column will focus on the amazing scientific discoveries – -those “Aha” moments — brought to us by Hubble. I’ll visit the Space Telescope Science Institute and bring you directly to the scientists themselves. I’ll also continue the saga of the young intern and the FBI agents.

Keep those comment coming! It’s a pleasure to have the opportunity to talk to people this way.

Colleen