|

Recently, several people asked: Why not replace the two instruments we’re repairing with new ones and why can’t we take the two science instruments inside the Shuttle and work on them there?

This is such an excellent question! The answer is truly an engineering marvel, so thank you for asking.

Hubble’s instruments were designed for easy removal and astronauts have removed radial and axial instruments on previous repair missions to Hubble. So, why aren’t we doing the same thing this time? Time is the answer.

The most valuable commodity on-orbit besides the astronauts themselves is the astronauts’ time. Every second of their time is choreographed more closely than an Olympian’s gymnastic floor exercise. Just as the gymnast’s every motion is fixed in her or his mind, the astronaut’s every motion outside the Shuttle is practiced so that a moment is not wasted.

When the spectrograph, STIS, failed, engineers led by Mike Weiss at Goddard, looked at every possible way to fix it, including the ones you’ve mentioned such as bringing it into the Shuttle Cargo Bay. But Mike found that “this approach would have taken about 2 additional hours of EVA time and would have required additional hardware to serve as a work bench. Pulling out the entire instrument would also mean overcoming potential contamination and electrostatic discharge concerns.”

I can’t resist taking this opportunity to talk about the symbiotic relationship between humans and their almost-robotic tools one more time! The NASA engineers surmounted yet another hurdle with tool design. If you’ve pulled electronics boards out of your computer, you’d think it might be pretty easy to do on-orbit. But Hubble has something called “wedgelocks” to make sure the electronic boards don’t rattle around on-orbit and so that there’s a path for heat to sneak out, keeping the boards cool. Imagine how frustrating it would be to pull out a stubborn electronics card in bulky gloves on Hubble! Resorting to swearing is usually the path we earthlings take on the ground. Somehow, it always helps, but it won’t help much on-orbit with Hubble.

So, NASA developed an extraction tool to neatly pull out a board. That tool was tested with the most stubborn test board ever made, and came out with flying colors and little debris.

Now that we know how to gain access to failed cards inside the instruments, pull them out and replace them, and put on a new simple cover, our marriage between tools and humans is complete. As Mike joked, the Hubble commercial might go like this: EVA Set-up — 3 hours. Pull and replace failed electronic cards — 15 minutes. Resurrect Science — Priceless.

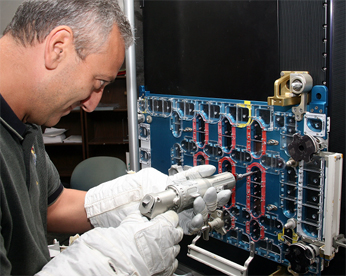

Here’s Mike Massimino practicing with the mini-power tool working on a test article.

I just love getting questions like this one that help us all think about the science and engineering marvels we’re creating today. I only wish I could start my career all over again and see what the next 30 years bring.

Colleen