From: Haley Smith Kingsland, Stanford University

Brian Seegers, Greg Mitchell, Elliot Weiss, and Brian Schieber (Photo by Brian Seegers)

The world-class waves of Black’s Beach in La Jolla, California, inspired Greg Mitchell to become a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. At age thirteen in the late 1960s, Greg read an article in Surfer magazine that featured Black’s Beach and the Scripps scientists pioneering the surf. Having spent his childhood summers crabbing, fishing, sailing, and surfing in Galveston, Texas, Greg immediately envisioned himself at Scripps with a career that would combine his fascination for the marine environment and passion for surfing.

As an undergraduate, a life-changing Biological Oceanography class with professor Daniel Kamykowski, then at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute, brought Greg even closer to Scripps. Kamykowski introduced the technical feasibility of using satellites to map phytoplankton distribution across the world’s oceans — today a robust operation — that set Greg’s graduate work at the University of Southern California in motion. Now a Research Biologist at Scripps, Greg’s ICESCAPE work focuses on improving current satellite algorithms so he can better understand how light supports the Arctic ecosystem through photosynthesis.

Satellites measure ocean color, data with which scientists can create detailed maps that illustrate regions of high chlorophyll, the green pigment phytoplankton use during photosynthesis. But interpreting satellite data is tricky because satellites measure the ocean’s color without distinguishing between chlorophyll and other materials in the water that all scatter and absorb light differently. “Satellites detect the color of the ocean,” Greg explains, “but you also need to understand what’s in the water. If we want the most accurate chlorophyll algorithm, we need to take into consideration these other things that are not chlorophyll and quantify how they affect the ocean color.”

Together with colleagues Rick Reynolds, Dariusz Stramski, and Stan Hooker, Greg’s team is investigating how particles within the open ocean both scatter and absorb light. “We know that particles like phytoplankton absorb light for photosynthesis,” Greg says, “but we’re also looking at all these other different constituents— bacteria, decomposing algae, other particles— to see how collectively they affect the absorption and scattering of light.” One aspect of Greg’s work explores colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM) — or photosynthetic biomass that’s decomposed by bacteria or other organisms — and how it absorbs light to affect ocean color. “If CDOM absorbs the light, that light’s not available for algae,” Greg says. “The Arctic Ocean contains more CDOM than other regions of the global ocean, but how much more, and how exactly that’s affecting the chlorophyll algorithms, are important to address.”

“We need to get the details of the Arctic ecosystem well-studied so that the algorithms and models are accurate,” Greg continues. To that end, his group is also collaborating with chief scientist Kevin Arrigo’s team to conduct lab experiments that will quantify algae’s absorption of light and determine the rates of photosynthesis. “There are certain things you can only do with a ship, and certain things you can only do with a satellite,” Greg explains. “We’re developing the mathematical equations that relate what we see on the ship to what the satellite can actually observe.” In conjunction with satellite data, their process models will not only allow scientists to better understand future scenarios related to climate change, but also reprocess historic data and start looking at an integrated picture of the Arctic Ocean over time. “I enjoy asking questions we don’t know the answers to,” Greg says. “Science is all about questioning the status quo and not just accepting prevailing paradigms.”

But this surfer’s life isn’t all about science. Greg has been writing a play — a modern-day Romeo and Juliet — with lyricist Brian Yorkey, Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize winner for the Broadway hit Next to Normal. And he’s spearheading cultural and biological conservation of South Pacific Islands as founder of the Pacific Blue Foundation. Known for his vivacity on the Healy, he and a few other researchers represent the science party on the ship’s Morale Committee. Even in the main science lab, Greg keeps spirits high with jokes and Cheshire cat sightings within graphs of data on computer screens. And back home, Greg doesn’t book his calendar before 10 a.m. “I may be in the lab at eight,” he says, “But if the waves are good, I’m surfing.”

Greg mentors Elliot Weiss (left), who graduated from UCSD this spring. “Working with young people is very important to me,” Greg says. “They share the same dreams, motivations, and excitement, and I love seeing them grow in their careers.” (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)

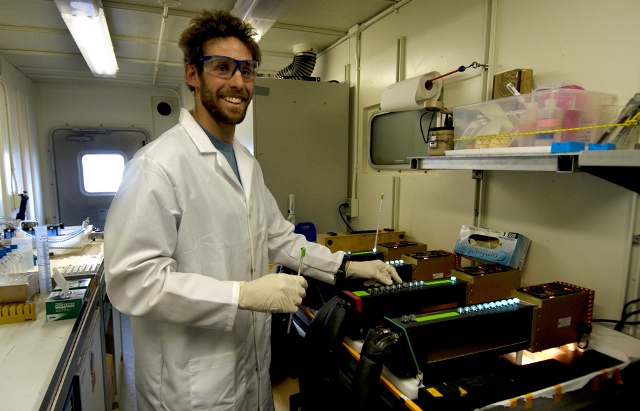

Brian Seegers works in a radioisotope experiment isolation van, where he measures how quickly algae in water samples take up radioactive carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)

Brian Schieber and Rick Reynolds deploy the optical package from the fantail. The package includes a fast repetition rate fluorometer (FRR) that measures photosynthetic physiology of algae, as well as an AC-9 that measures absorption and scattering of light within nine different wavelengths. (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)

Rick Reynolds, Kuba Tatarkiewicz, and Greg Mitchell rinse the optical package upon its return to the fantail. (Photo by Kathryn Hansen)