From: Kevin Arrigo, Stanford University

Newly initiated “polar bears” Gert van Dijken, Kevin Arrigo, Matt Mills, Kate Lowry, Molly Palmer, Zach Brown, and Haley Kingsland on the fantail. (Photo by Gert van Dijken)

“The changes going on in the Arctic Ocean are frightening,” I tell the scientists and crew members in the audience.

I had just finished a lecture about some of my Arctic research and someone asked me what I thought about the future of this fragile environment. Melting of Arctic sea ice is pretty familiar to most people by now, but there are other, equally worrisome things going on. Biological productivity has ratcheted up and the timing of many key events is shifting. The sea ice is melting earlier in the spring and advancing later in the autumn. Phytoplankton are beginning their growth spurt earlier than ever before. Why is this a problem? Many animals key their migration to be in the Arctic when it is at its most productive. Arctic terns and gray whales are two prime examples. What will happen to them as the timing of that production changes? There is an enormous experiment going on in the Arctic and we can’t control it and we don’t really understand it.

That’s why I got involved in ICESCAPE. There are fundamental questions to which I want to know the answers. Is the biological productivity of the Arctic Ocean really increasing, and if so, why? Why is the timing of this production changing? To answer these questions, we need to know what controls the growth of these miniscule plants that manufacture the food for an entire ecosystem. Is it light? Is it a nutrient like nitrogen, the fertilizer of the sea?

To answer these questions, we need to make measurements. Lots of measurements. And we need to do experiments. On ICESCAPE, my research group does both – with the help of the rest of the ICESCAPE team, of course.

It begins with either Matt Mills or Gert van Dijken (depending what time of day it is) telling the operators of our water sampler what depths to grab water from. They always want surface water, but sometimes the bugs are more numerous deeper down, so they may ask for water from there, too. Then Zach Brown and Kate Lowry swoop in, grab the water and bring it into the lab. Most of the water gets collected on little filters to see what’s in it, and Haley Kingsland measures their chlorophyll concentration. Gert injects some of the water with radioactive carbon and it sits either in the sun for a day or in a “photosynthetron” for an hour – that’s how we measure algal growth. In the meantime, Molly Palmer takes some of the water and tracks the algae’s behavior when zapped with lots of light. Finally, Matt and Zach use some of the water to measure how quickly the algae can gobble up different flavors of nutrients. And we do this day, after day, after day.

In the end, we hope to have a better picture of what Arctic algae like and dislike. What makes them thrive and what makes them crash. Why they are so much more productive now than they used to be. Why they are starting to grow earlier in the season.

Armed with this information, we will be in a much better position to interpret the changes we are observing today, and more importantly, to begin to understand what the future is likely to bring.

Gert van Dijken accepted an award on behalf of the science party for 21 days of service

above the Arctic Circle. (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)

Zach Brown, Matt Mills, and Kate Lowry before an ice station.

(Photo by Gert van Dijken)

Elliot Weiss and Zach Brown filter water samples for examination. (Photo by Gert van Dijken)

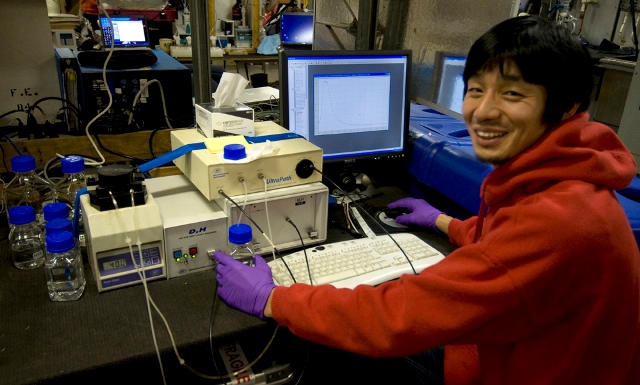

Haley Kingsland measures the chlorophyll concentration of water samples with a fluorometer.

(Photo by Luke Trusel)

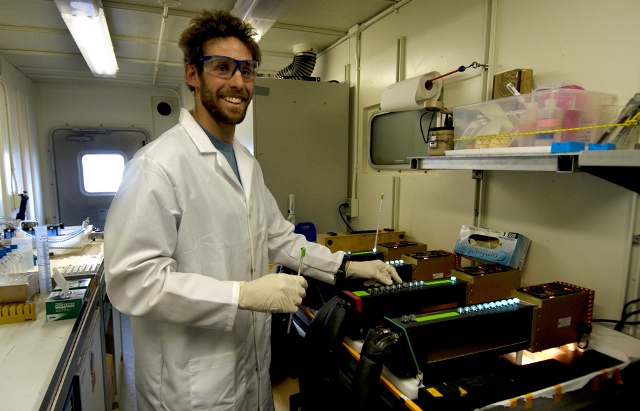

Molly Palmer records algae’s behavior under high light conditions using the Fast Repetition

Rate Fluorometer. (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)