Today’s blog is from Henry Throop, a New Horizons science team member and senior research scientist with the Planetary Science Institute in Mumbai, India.

In a previous blog post, I wrote about software the New Horizons team used to image Pluto. Here, I’m going to talk about my work photographing the team itself.

We knew that New Horizons would be a historic mission scientifically. But we also knew it was important to document the human side of the encounter—the successes as well as frustrations. Just as we remember Neil Armstrong’s words and the shaky video from the surface of the moon, we knew that our team members’ activities would also form their own historical record.

APL, home of New Horizons mission operations in Laurel, Maryland, arranged for me and five other members of the science team to carry cameras as we worked. We were allowed access to the science working areas and public and press zones (though not mission operations, where flight controllers actually command the spacecraft).

While I’ve spent years photographing around the world, there was nothing more exciting than to point my camera at my friends and colleagues on this epic journey to the frontier of the solar system. Below are some of my favorite images.

Although New Horizons had been in flight for over nine years, it was only two weeks before the Pluto encounter that we first detected Pluto with LEISA, the spacecraft’s near-infrared spectrometer. In the image above, members of the Composition team compare their three independent analyses of the spectrum, which showed the very first detection of water ice. Why three different models of the same thing? Just like an airplane has multiple altimeters, we wanted to be sure that we weren’t deceived by errors in any one model.

In the Payload Engineering room, shown above, Maarten Versteeg and Tommy Greathouse work with data from the Alice ultraviolet spectrometer. This was taken 36 hours before Pluto close approach, and the instrument had sent back its very first spectrum of Pluto. Up until now, this instrument had been too far from Pluto to detect it.

In addition to the snacks keeping the team going, there are two New Horizons models here. At right is the detailed scale replica. But the more frequently used one is the small yellow model on the speakerphone, marked with the rotational axes we use to point it. A typical observation might be “Point +X toward Pluto, roll -Y to north, and then do a 30-degree scan around -Z.” We used models like this frequently when planning observations.

On the morning of closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, the New Horizons team woke up earlier than normal so we could get our eyes on the highest-resolution “global” images that had been taken about 14 hours earlier. Two members of the team worked overnight to process them in time for our team meeting at 5 a.m.

In the above photo, members of the science team see the young and un-cratered “heart” of the informally named Sputnik Planum close-up for the first time.

On the day of encounter, New Horizons was busy observing Pluto, except for one short break to transmit a status update to the nervous team on Earth. This “phone home” signal was to be received around 8:52 p.m. EDT and was the emotional highlight of the encounter.

Setting up a few shots of the signal’s arrival, I was focused on my colleagues (in the black shirts above the railing), and I didn’t pay much attention to the man in the suit below them. But that is NASA’s Senior Public Affairs Officer Dwayne Brown, and it was his reaction that really made this shot!

A day after flyby, we received new images of Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. Charon was discovered in 1978 by Jim Christy. Christy suggested the name “Charon” – but he pronounces it with a soft “Sh” instead of a hard “K,” in reference to his wife, Charlene.

Jim and Charlene were at the front of the APL auditorium as the images were revealed. While Jim watched quietly, Charlene was taking photos of it all – she told me she was e-mailing them to her family as fast as she could.

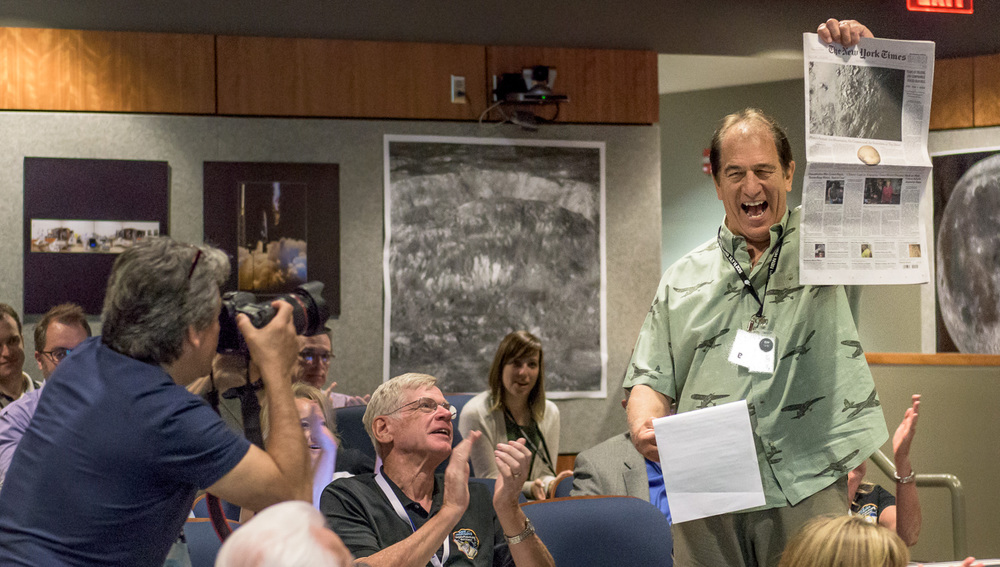

Our daily 8 a.m. science results meetings would often include an update on media coverage from David Aguilar, who led the team of writers assisting the science and public affairs teams with news and image releases. Here he reacts to our front-page New York Times coverage on July 16, 2015.

Over the course of seven weeks, I took close to 10,000 photos. I’m grateful to APL and the mission for allowing us to document our extraordinary time exploring Pluto—both from afar, and here on Earth.

Credit: Michael Soluri