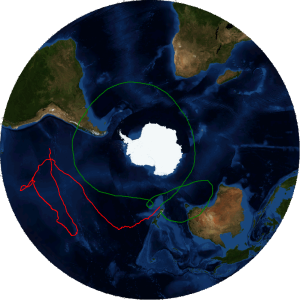

Forty days at float as of Saturday, June 25, and NASA’s super pressure balloon (SPB) is presently flying above the south Pacific as it continues on its long-duration technology test and science flight.

For the past two weeks, the balloon has etched out a whimsical groundtrack over the Pacific, slipping out of the more southerly stratospheric cyclone pattern and then floating nearly to the equator before turning west, south, and now east toward South America.

“The balloon has flown longer than its predecessor, flying through the rigors of the heating and cooling experienced in the day/night cycle,” said Debbie Fairbrother, NASA’s Balloon Program Office chief. “We continue to monitor the balloon, conducting daily analyses of the balloon’s health and trajectory.”

The balloon is designed to float at a constant pressure altitude of 7 millibars. However, the actual altitude at float is also dependent on the environmental conditions where colder weather below could lead to lower float altitudes. To date, the balloon has flown over a number of cold storms, which has resulted in the balloon losing its differential pressure and experiencing some altitude variance at night.

“The heating and cooling cycle puts a lot of stress on the balloon, but it was engineered to withstand the extra wear,” said Fairbrother. The previous record flying through the day/night cycle was 32 days, 5 hours, set in 2015 with an SPB flight that launched from Wanaka, New Zealand. The overall record for any SPB flight is 54 days, set by a 7-million-cubic-foot SPB flight over Antarctica in 2009.

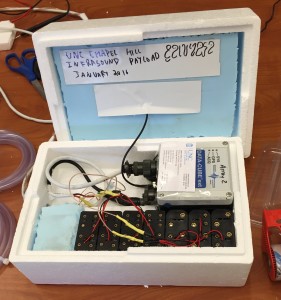

Aside from the technology test of the balloon itself, the SPB is carrying the Compton Spectrometer and Imager (COSI) gamma ray telescope. The COSI team reports that the science instrument continues to collect good data.

Balloon flight operators at NASA’s Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility in Palestine, Texas, are monitoring the mission around-the-clock. Anyone can track the progress of the flight from this website: http://www.csbf.nasa.gov/newzealand/wanaka.htm