Completion of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s optical alignment has moved us into the final phase of commissioning the Science Instruments. During this final phase the Webb team and instrument scientists will test all the modes and operations for the four science instruments to measure their performance, calibration, and overall observatory operations.

While the mirrors are slowly cooling to their final operating temperatures, the Webb team is preparing for the thermal stability test. We asked Erin Smith, the Webb deputy observatory project scientist, to tell us about the hot and cold of this test.

“Webb’s five-layer sunshield keeps the telescope and science instruments cool and shielded from the Sun, Earth and moon. This protection allows Webb to make measurements of the infrared universe, which requires a cold telescope and cold instrument optics. However, as Webb points to different targets around the sky, the angle of the Sun on the sunshade changes, which changes the thermal profile of the observatory. These variations in temperature can induce small changes in the observatory, and affect Webb’s optical quality, pointing, observed backgrounds, and other parameters.

“The thermal stability exercise will measure these changes by moving between the extremes of Webb’s field of view, from the hot to the cold attitude, spending multiple days in the cold attitude, then slewing back to the hot attitude. During this time, the Webb team will measure the thermal stability, pointing performance and optical wavefront drift. In addition to measuring the performance of the observatory, the team will also check the thermal modeling used to predict observatory behavior.

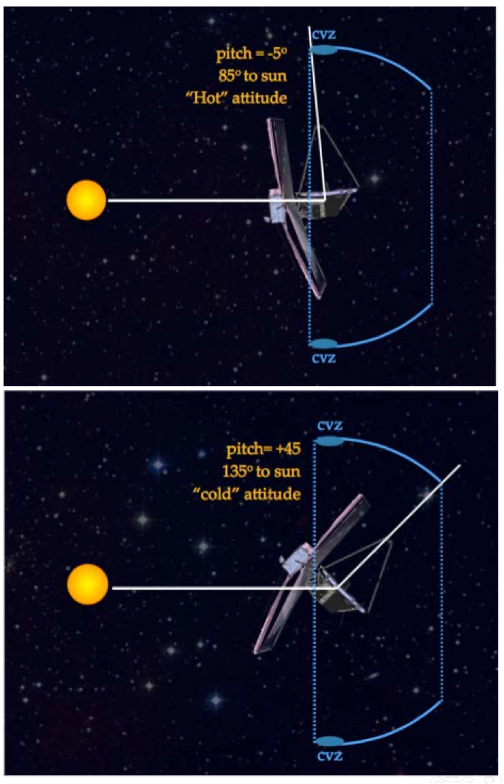

“With the telescope shielded from the Sun, Webb observes an annulus, or donut, on the sky at any given time, called the “field of regard”. Over the course of each year, this annulus sweeps out the whole sky. Pitch is the angle towards (negative) or away (positive) from the Sun. Webb points between pitches of -5 and +45 degrees. The “hot” attitude is at 0 degrees, with the Sun squarely illuminating the sunshield. The “cold” attitude is +45 degrees, with the sunlight reduced by a factor of cosine(45 degrees), about 0.7.

Top: Webb at the ‘hot’ attitude, pointed near the continuous viewing zone (CVZ); bottom: Webb at the ‘cold’ attitude.

Credit: NASA/STScI

“To begin the thermal stability test, the Webb team will point the observatory in the hot attitude at about 0 degrees pitch, and keep it there for a five days while it thermally stabilizes. The team will make baseline measurements of the pointing stability, optical wavefront error and any oscillations caused by the instrument electronics. Once this baseline has been established, the team will slew the observatory to the cold attitude, about +40 degrees pitch. Immediately after the slew, the team will use NIRCam’s suite of weak lenses for 24 hours to continuously measure any short-timescale effects on the wavefront. After this, the team will monitor the stability of the telescope every 12 hours, to measure the thermal stabilization of the telescope itself.

“The observatory will spend more than a week at the cold attitude, until the temperatures stabilize. Then Webb will slew back to the hot attitude, and the team will take high-cadence pointing stability data using both the FGS/NIRISS and NIRCam instruments. The MIRI instrument will also make observations at both attitudes, to understand how the changing thermal environment affects the mid-infrared background levels. During this long test, the Observatory will not sit idle; some instrument commissioning activities are compatible with the hot and cold pointings.

“When assembled together, the data from the thermal stability tests will allow the observatory team to better understand how the observatory behaves thermally. Although the changes are expected to be very small, Webb is so sensitive that they could make a difference as we optimize the telescope’s performance. This real-world calibration of the complicated thermal models used by Webb’s developers will help to inform future observing strategies and proposals.”

-Erin Smith, Webb deputy observatory project scientist, NASA Goddard

-Jonathan Gardner, Webb deputy senior project scientist, NASA Goddard

-Stefanie Milam, Webb deputy project scientist for planetary science, NASA Goddard