Ivona Cetinić is a biological oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

What is your favorite ocean or atmospheric related book or movie?

I’m a science fiction fan. Definitely “Abyss.” I don’t know why, but it’s been my favorite ever since I was a kid. I’m sure there are better ones, but it’s the only one that comes into my head movie wise. For a movie it was always, always, always “Abyss.”

What is your background? What do you do for PACE?

I am an oceanographer. I am interested in phytoplankton community structure and how it interacts with the environment, and also how the environment interacts with phytoplankton community structure. That’s how I ended up developing better tools to study phytoplankton.

For PACE, I am in charge of anything that has to do with biogeochemical processes in the oceans. Not just phytoplankton, but also the elements (such as carbon) and energy that phytoplankton move around, and other types of carbon, sediment, or organic material that float around the ocean. So, I take care of those algorithms and make sure that they look nice and pretty once we launch.

What are you most looking forward to during launch?

The launch itself, since I have never been to a single launch. So I’m excited for the countdown, and being surrounded by family, friends, and colleagues, and everybody enjoying that moment.

What are you most looking forward to post launch?

The first light images and the first data. I’m looking forward to getting to start playing with the data as soon as I can get my hands on it. We’ve been testing algorithms and I just want to get some real data!

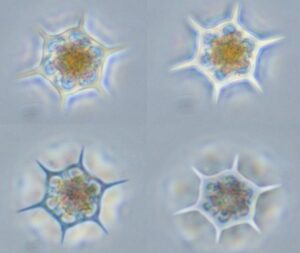

Do you have a favorite phytoplankton?

I shouldn’t have favorite children! But there is one that I really like a lot – it’s called Dictyocha speculum. It’s really cute. This “guy” looks like a little star, and to me looks a little bit like the star on top of the PACE logo.

Since PACE will be looking at all these different colors of the ocean, do you have a favorite color and why is it your favorite color?

I think you’ll see me in black all the time, which isn’t a color. It’s really hard to define color because the color is dependent on the thing as well as the light that is bouncing off that thing. And when something is black, that means that eats up everything, all the light. There’s nothing coming back towards your eyes, that’s what black is. I think it just kind of goes back to my teenage years everyone was comfortable person in black. But when it comes to real colors, probably purple, lilac, bluish.

What advice would you have for aspiring oceanographers who are interested in working for NASA?

Never give up. Never surrender. Really jump at any opportunity that opens up to you, just because you will never know where it’s going to lead. And it might not lead right to where you want to go, but it’s much better than sitting in one spot and thinking “Oh, what would be happening, where would I be if I didn’t take that opportunity?” Just try to jump on any opportunities out there. I was lucky to have the doors open every time and I was just jumping in everything that was available to me. I think that’s the route that got me to NASA.

What is a fun fact about yourself? Something that people might not know about you?

I like music a lot, and I play many instruments. Currently, I play drums in an all-women, Afro-Brazilian band.

What is one-catch all statement describing the importance of PACE?

PACE will give us a view of the ocean and atmosphere that we have never had before. It opens up so many possibilities that we don’t even know about. I think PACE is going to give us so much more insight than we expect about the ocean and the atmosphere and interactions between them.

Header image caption: Ivona happily posing with the PACE observatory. Image Credit: Dennis Henry

By Erica McNamee, Science Writer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center