Today’s post is written by Alex Parker, a research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, working on NASA’s New Horizons mission.

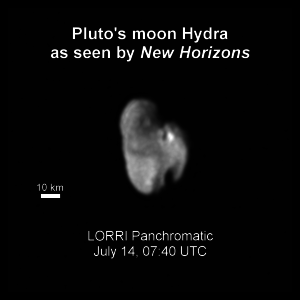

As New Horizons flew by Pluto, it recorded spectacular images of the icy world’s surface using the LORRI and MVIC cameras. It recorded the plasma and dust environments with the PEPSSI, SWAP, and SDC instruments. But one instrument, designed to measure the composition of Pluto and Charon’s surfaces, did something you might not expect: it recorded the first movies from the edge of our solar system.

Recorded with a 256 x 256 pixel camera at under two frames per second, they are not exactly HDTV. However, they are movies. And they are in color. Sort of.

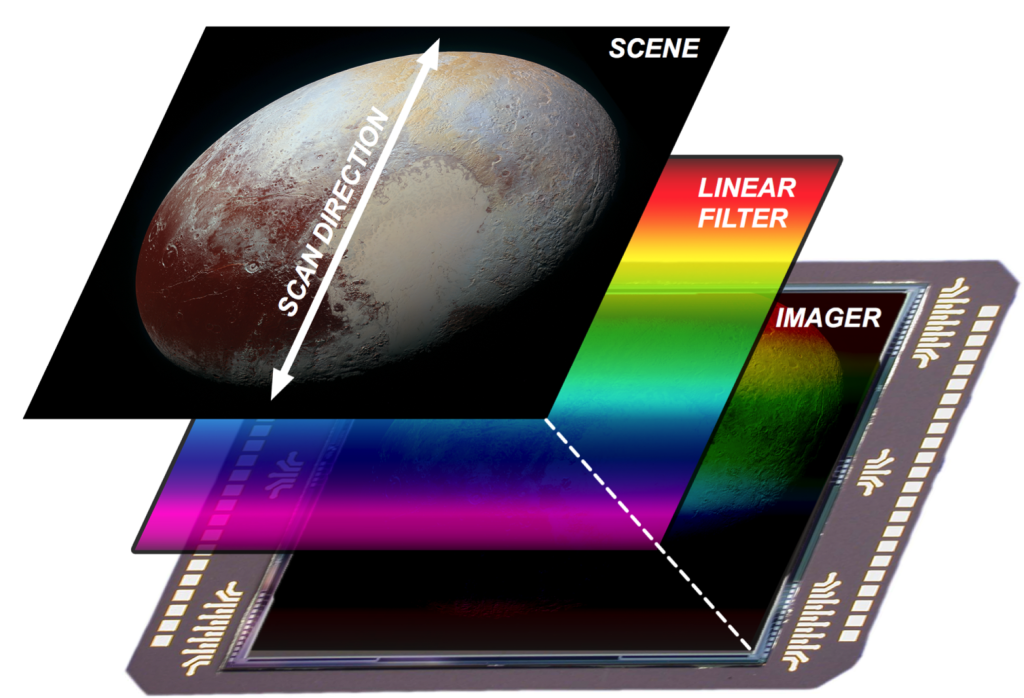

The instrument is LEISA, New Horizons’ infrared imaging spectrometer. It is an extremely clever instrument; it takes 2-D images just like a normal camera, but it takes them through a linearly-varying filter. One side of the camera can only see light of one specific wavelength of infrared light (light that has longer wavelengths than can be seen by our eyes), and each row of pixels can see a subtly different wavelength.

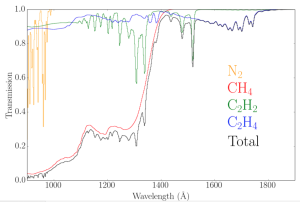

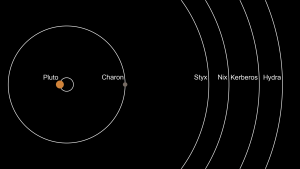

This linear filter allows light with wavelengths as short as 1.25 microns (a micron is one millionth of a meter; human eyes can perceive light with wavelengths as short as 0.39 microns to long as 0.7 microns) to fall on one side of the image sensor, and smoothly changes to allow light with wavelengths as long as 2.5 microns to fall on the far side of image sensor. This wavelength range was selected because many ices and other materials that exist on the surface of Pluto that have spectral features in this wavelength range that can uniquely identify them, like a fingerprint. We use this instrument to map the distribution of these ices and other materials across Pluto and its moons. A second linear filter to one side of the imager is designed to provide a finer measurement of the spectrum in a region of particular interest between wavelengths of 2.1 to 2.25 microns.

The effect is much like looking through a stained glass window designed for infrared eyes. By scanning this image sensor with its linear filter across a scene and quickly recording many images during the scan (like a movie), LEISA builds up a two-dimensional map of the scene in front of the camera with a measurement of the infrared spectrum (the brightness versus wavelength) at every location in the image. It makes this complex measurement with exactly zero moving parts — highly reliable for deep-space operations.

The side-effect of collecting this scientifically-important data set, capable of measuring the composition of every location on the surface of Pluto and Charon that is imaged, is that LEISA collected low frame rate infrared color movies of Pluto and Charon as seen by New Horizons during its flyby.

Pluto Through Stained Glass: A Movie from the Edge of the Solar System. This colorful movie drifting across Pluto by was recorded by New Horizons’ LEISA infrared imaging spectrometer during the July 14 closest approach. The movie has been sped up approximately 17 times from its raw frame rate, and the infrared colors that LEISA sees have been translated into visual colors. Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Alex Parker

The animation shown here is one such movie collected by New Horizons during its flyby of Pluto. Each pixel is colored to show the relative wavelength of light that each pixel was allowed to see by LEISA’s linear filter. However, since LEISA sees in infrared light, the colors LEISA can see have been re-mapped for this video onto the human visual spectrum — the rainbow. The video has been sped up from its raw frame rate to show the motion smoothly.

In this animation, Pluto drifts by outside the spacecraft as New Horizons scans LEISA across the surface. As Pluto slides beneath the camera, you can see it nod back and forth from the top of the frame to the bottom — these changes in direction are due to New Horizons thrusters firing during the recording of the movie.

This is what you would have actually seen if you were on board the New Horizons spacecraft on July 14, looking out at Pluto through a stained glass window with infrared eyes.

The composition of Pluto makes itself apparent in the animation. Dark bands top-to-bottom correspond to absorption by specific chemicals on the surface of Pluto; many of the bands visible in this view are due to absorption from solid methane ice. However, as some terrains slide by, you can see that they do not become dark under those bands like other terrains; in these areas, the chemical responsible for that absorption is absent.

The discovery of water ice on Pluto was made using the data in this movie. The discovery of ammonia ice within the informally-named Organa crater was made using data from a similar movie of Charon. The New Horizons composition team is busy analyzing these and other movies taken by the LEISA instrument in order to further understand what the surface of Pluto and Charon are made of and how they might be changing with time.

But please — just take a moment and imagine you were on board our little robotic emissary to the farthest worlds ever explored, watching Pluto come into view through a colorful window on the side of the spacecraft. Sure, it might not be in HD, but I promise that you’ve never seen anything like this before!