Editor’s note: This article was updated on April 4 to provide the latest target launch date information.

NASA is announcing two small CubeSats missions to launch on a commercial dedicated rideshare flight as part of the agency’s Educational Launch of Nanosatellites (ELaNa) initiative, which helps advance scientific and human exploration, as well as reduce the cost of new space missions, and expand access to space.

The CubeSat missions, which will study parts of Earth’s atmosphere and its radiation belt dynamics, are targeted for launch no earlier than April 2023 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

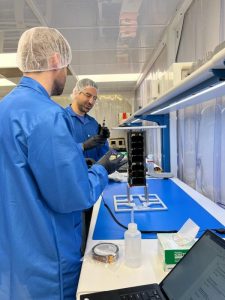

The Colorado Inner Radiation Belt Experiment (CIRBE) and Low-Latitude Ionosphere/Thermosphere Enhancements in Density (LLITED) are ELaNa missions 47 and 40, respectively.

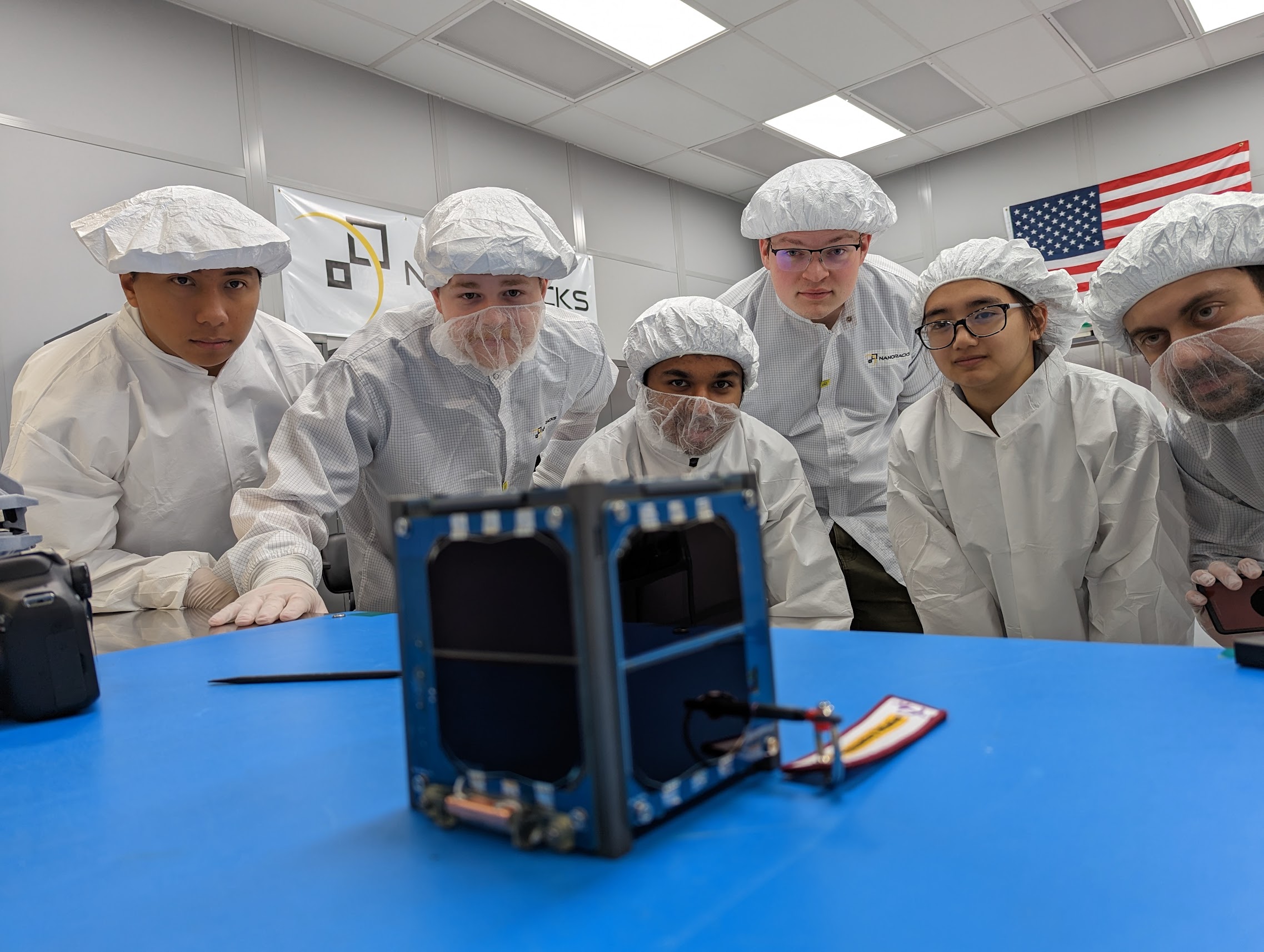

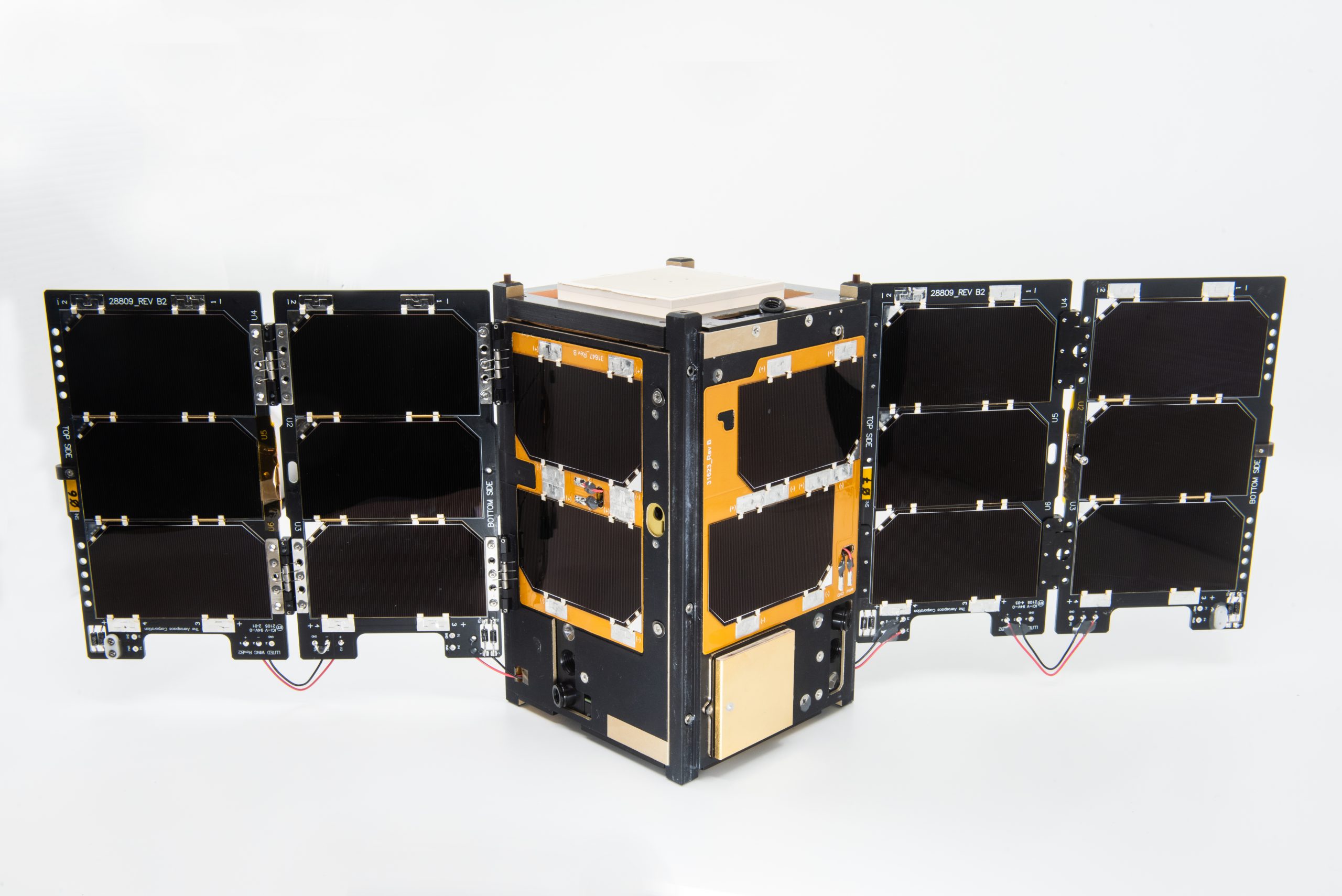

CIRBE is a 3U CubeSat (1U, or unit = 10cm x 10cm x 10cm) from the University of Colorado Boulder, designed to provide state-of-the-art measurements within Earth’s radiation belt in a highly inclined low-Earth orbit. CIRBE aims for a better understanding of radiation belt dynamics, consequently improving the forecast capability of the energetic particles known to pose a threat to orbiting satellites as well as astronauts during spacewalks.

“Despite being the first scientific discovery of the space age, there are still many unsolved puzzles regarding the dynamics of these energetic particles,” said Dr. Xinlin Li, CIRBE principal investigator and professor at the university’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics.

CIRBE’s sole instrument, Relativistic Electron Proton Telescope integrated little experiment-2 (REPTile-2), is an advanced version of an instrument previously in space from 2012 to 2014. The original REPTile could detect three energy channels, whereas REPTile-2 can distinguish 50 distinct channels, providing far greater measurement of elusive high energy particles with potential to damage satellites and penetrate spacesuits. REPTile-2 will measure the energies of incident electrons and protons, with its data downlinked to the ground via S-band radio. At mission’s end, the spacecraft’s orbit will begin degrading, eventually re-entering the atmosphere and burning up.

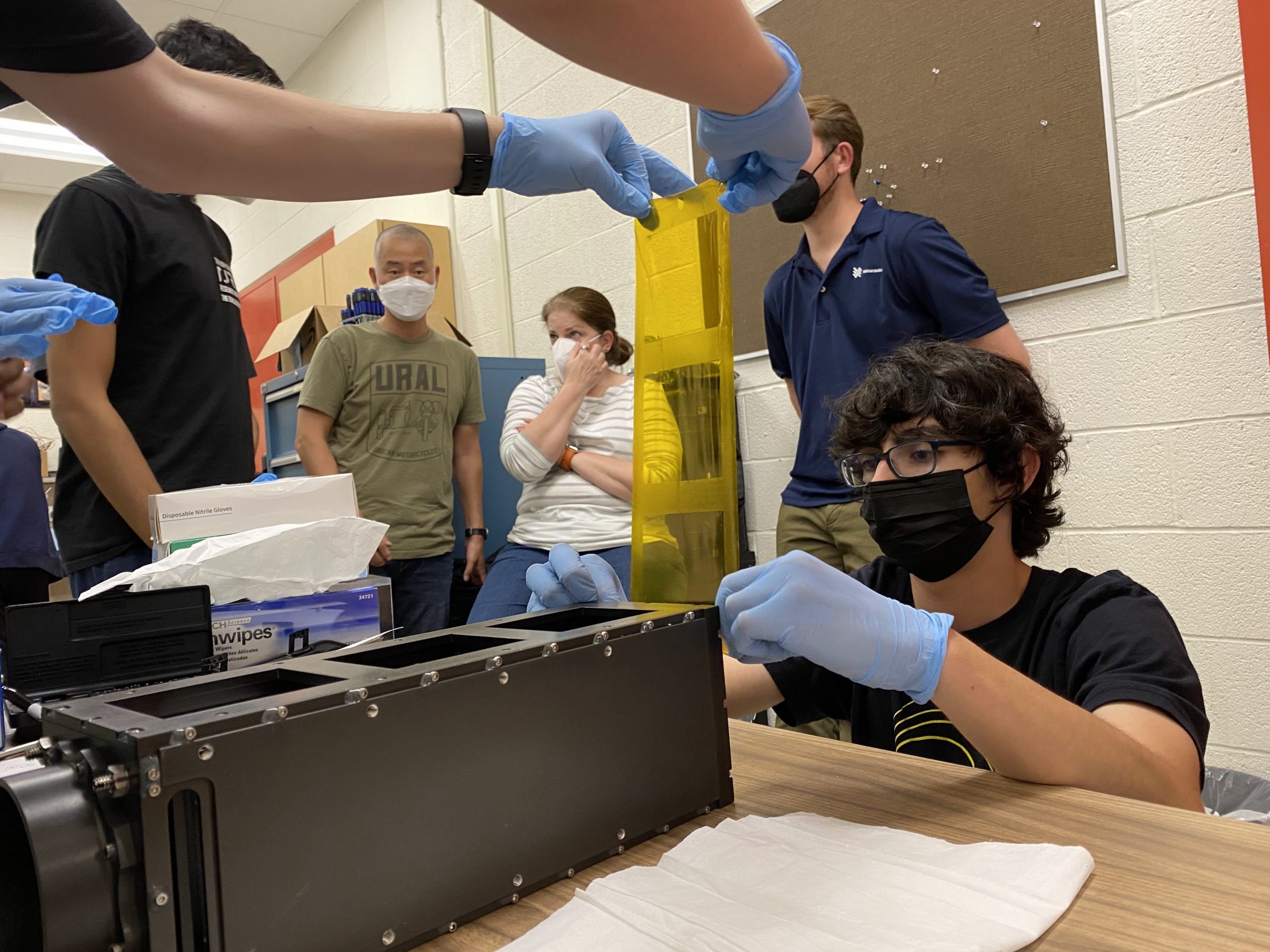

NASA’s LLITED consists of two 1.5U CubeSats developed by The Aerospace Corporation, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida, and the University of New Hampshire (UNH). LLITED will study two late-day features of Earth’s atmosphere between 217 to 310 miles, with the aim of gaining a greater understanding of the interactions between the neutral and electrically charged parts of the atmosphere, consequently improving upper-atmosphere modeling capabilities and predictions for orbital proximity and re-entry.

“For the first time, we will be able to make simultaneous and co-located measurements of two phenomena in lower thermosphere/ionosphere – Equatorial Ionization Anomaly (EIA) and Equatorial Temperature Wind Anomaly (ETWA) – from a CubeSat platform,” said Dr. Rebecca Bishop, principal investigator for LLITED. “The two LLITED CubeSats will be able to observe changes in time and space of the two features.”

Both LLITED CubeSats carry three science instruments – a GPS radio-occultation sensor provided by Aerospace, an ionization gauge from UNH, and a planar ion probe provided by Embry-Riddle. Working together, the instruments will show how these atmospheric regions of enhanced density form, evolve, and then interact with each other after sunset.

“Because CubeSats can weigh 100 times less than larger satellites, missions such as LLITED demonstrate the potential of these small and cost-effective spacecraft to perform cutting-edge, comprehensive science experiments that previously were not feasible within traditional program resources,” said Bishop.

NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative (CSLI) supporting the agency’s Launch Services Program at Kennedy Space Center in Florida provides launch opportunities for small satellite payloads built by U.S. universities, high schools, NASA Centers, and non-profit organizations. To date, NASA has selected more than 225 CubeSat missions, representing participants from 42 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and over 115 unique organizations.