The international team who built and operate the Large Area Telescope, one of two instruments on the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope (often known simply as Fermi), will have a meeting at CERN (the European particle accelerator facility that runs the Large Hadron Collider).

The program includes a full day of public scientific, outreach and art projects on 29 March in CERN’s Main Auditorium, designed to promote scientific and cultural collaboration with CERN users interested in learning more about the LAT.

Over the course of the day, scientists will present results from Fermi and from CERN’s experimental and theoretical groups active in dark matter searches and the study of cosmic rays.

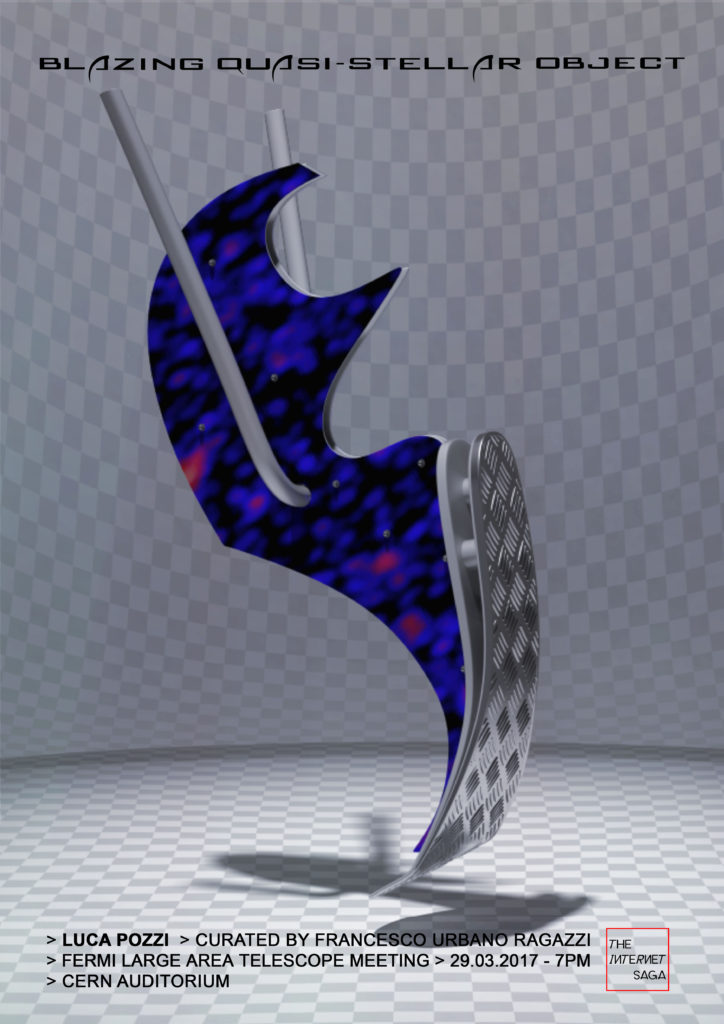

At 7 p.m., the collaboration will present the Blazing Quasi-Stellar Object, a multimedia work by Italian artist Luca Pozzi and curated by the Francesco Urbano Ragazzi duo. The work is structured as a lecture-performance featuring visual animations. Pozzi has a profound fascination for the scientific ideas underlying modern multimessenger astrophysics and feeds his inspiration through a continuous dialogue with scientists. Pozzi will deliver his lecture on Tiziano’s painting Bacco e Arianna and will guide the audience in an analysis of this late Renaissance masterpiece focusing on the complex stratifications connecting this painting to the frontiers of multimessenger astrophysics.

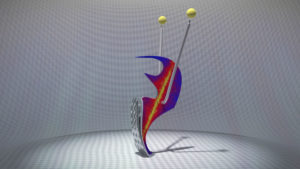

In addition, there is a 3D animated screen saver, The Big Jump Theory, designed by the artist and expressing an imaginary theory inspired by quantum gravity, gravitational waves and the gamma-ray sky as seen by Fermi.

Cake by Sylvia Zhu, David Green and Judy Racusin. Pulsar Technical Consultant was Megan DeCesar

Cake by Sylvia Zhu, David Green and Judy Racusin. Pulsar Technical Consultant was Megan DeCesar