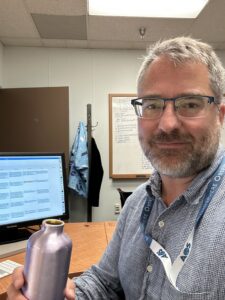

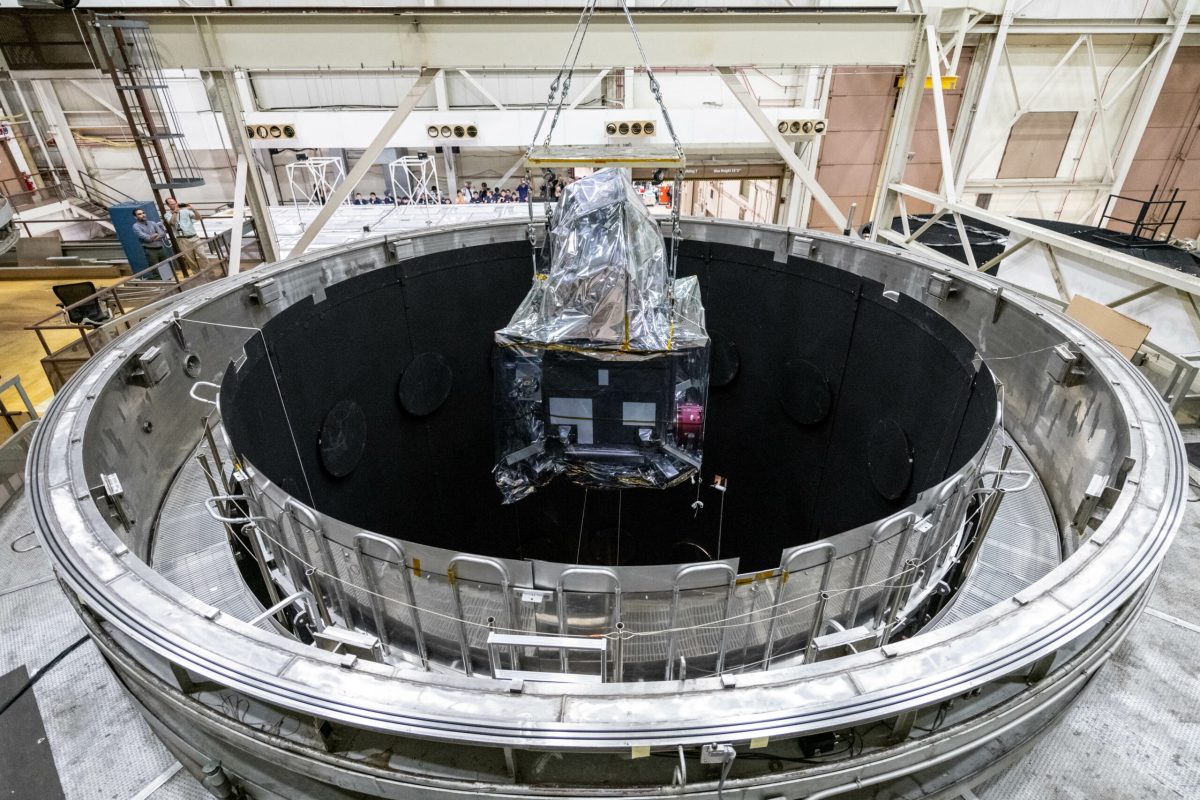

Joaquim Goes, a professor of remote sensing research at Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University Climate School, is a member of the PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem) Northern Indian Ocean Validation group. The group is one of many in a campaign set out to gather data around the world to validate the information that the PACE satellite is collecting up in orbit. In June, Goes, along with team members from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland; Space Applications Center (SAC); ISRO (Indian Space Research Organization); and the Indian National Center Ocean Information Systems, embarked on a research vessel to the Bay of Bengal. They gathered data on phytoplankton communities and ocean color pigments.

Why did you choose that location for your research campaign?

The Bay of Bengal is connected to the Indian Ocean, but it’s strongly influenced by freshwater, which makes it a little different than many other bays and seas. We wanted to go somewhere that could show us the effects of this freshwater influence, and plus there isn’t a lot of historical data from that region. It presented us with the opportunity to investigate riverine influence on phytoplankton community structure, biogeochemistry, and ocean optical properties.

How did you gather your data?

We had several bio-optical instruments on board the research ship, some of which operated continuously as the ship moved along a pre-determined cruise track while others were deployed when the ship stopped, usually at mid-day when PACE and Oceansat-3 were passing over our study area.

Some of the optical instruments measured the color of water using above water instruments, while others were deployed in the water allowing us to make ocean color measurements at different depths. The color of the water is the result of the interaction of sunlight with seawater and its constituents which include phytoplankton, minerals and other non-algal particles and colored dissolved organic matter. For example, if there are more phytoplankton in the water their photosynthetic pigments strongly absorb blue and green light, while scattering back green light, making the water green. The types of pigments phytoplankton contain vary, and the color they render the water can be used to deduce different phytoplankton types.

Instruments like the FlowCam helped us image the kinds of phytoplankton in the water, while others allowed us to study their ability to photosynthesize and fix atmospheric carbon dioxide. We also filtered water samples so that we could measure the types of phytoplankton pigments as well as the absorption of light by phytoplankton and non-phytoplankton particles and colored dissolved organic matter.

How are you planning on using PACE data?

We are really interested in looking at outbreaks of harmful algal blooms, which are becoming a water quality issue in the Northern Indian Ocean. These blooms are so widespread that they cannot be adequately sampled by ships alone. To address this, we need data to develop algorithms that will help us identify these blooms from space. PACE data and other satellite products can be implemented into early warning systems for harmful algal blooms which are causing havoc worldwide.

What do you enjoy most about field work?

You get to meet new people. The feeling of comradeship and building networks is so exciting to me. I’m at a point in my career where I feel that it’s important for young people, especially from developing countries, to learn how to use the latest instrumentation and connect with others to support their research endeavors. On this campaign we had a diverse group of ocean and atmospheric scientists from NASA, the University of Washington, Notre Dame, and UMass Dartmouth, as well as two institutions from India, with many young people involved. We worked very closely with them to perfect some of the data collection methods and analyses protocols. Overall, the opportunity to meet new people and explore new places is what makes field work so enjoyable.

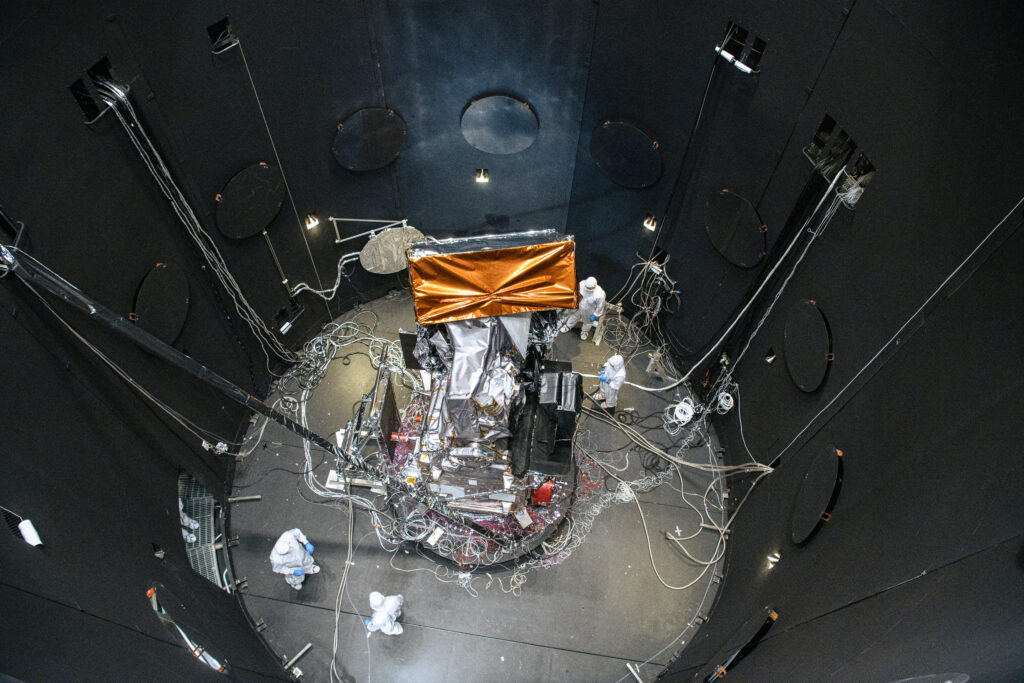

Header image caption: NASA PACE and ISRO Oceansat-3 calibration and validation teams from Space Applications Center, ISRO, Indian National Center for Ocean Information Services, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University along with Chief Scientist Dr. Craig Lee. Courtesy of Joaquim Goes

By Erica McNamee, Science writer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center