As you all probably know, this week we celebrated the 50th anniversary of NASA and it is also the 51st anniversary of Sputnik and the start of the space age. Last year on “Columbus Day”, I wrote a note to my shuttle troops on these anniversaries. It may be cheating to recycle that letter, but I think it still applies. Here it is:

————————————————————————————————————–

Calendars are funny things. We count time as very important and try to keep track of special days. But the calendars and the seasons don’t always match up. For example, every school child knows that

Well, not exactly.

It was October 12 on the Julian calendar which was already out of sync with the universe by 9 days in 1492. So we should really celebrate the discovery of

And who really sighted land first? In the wee hours of October 12 (old style), it was Juan Rodriguez Bermeja de Triana aboard Their Most Catholic Majesty’s ship Pinta that called out “land ho” (Tierra!).

So Bermeja discovered

So much for the history books.

Fifty years is a long time.

We have just celebrated 50 years of space exploration. How do our accomplishments rack up next to those of the age of discovery?

The first permanent settlement in what came to be the

How about exploration? One of the greatest expeditions came 48 years after

And if you study their own words, you might just come to the conclusion that the search for gold was their biggest motivation. No gold, no glory, few converts, and

Not that those early explorers lacked courage. Courage was in abundance. Hernando Cortes took on the mightiest empire in the new world, the Aztecs. Against an empire that on a regular basis could put upwards of 150,000 warriors on the battlefield against their enemies, Cortes marched in with about 400 soldiers of fortune. Mostly by bravado and trickery the Castilians defeated their vastly more powerful adversaries. Well, the captain from

One of Cortes’ officers, Bernal Diaz, wrote the definitive eyewitness account of those days in 1521. He could hardly believe his own story:

“Those readers who are interested by this history must wonder at the great deeds we did in those days: first in destroying our ships; then in daring to enter that strong city [Mexico City] despite many warnings that they would kill us once they had us inside; then in having the temerity to seize the great Montezuma, king of that country, in his own city and inside his very palace, and to throw him in chains. . . . Now that I am old, I often pause to consider the heroic actions of that time. I seem to see them present before my eyes. . . . For what soldiers in the world, numbering only four hundred – and we were even fewer – would have dared to enter a city as strong as

It is not surprising that Bernal Diaz did not title his memoir The Exploration of New Spain, but gave the book the more accurate title: The Conquest of New Spain.

As explorers, the early Castilians did not know what they were doing. They left no accounts of the wonders of the land or its people, merely the dreary endless stories of fighting, treachery, deception, and blood.

By comparison, peacefully landing a dozen expeditions on our nearest celestial neighbor and building a great international laboratory with the cooperation of the leading nations of the world doesn’t stack up too badly. Comparing the first 50 years, that is with their first 50 years.

What else can we learn about this comparison of explorations?

Here is a short list: Sometimes exploration goes slower than you would expect. Don’t expect the history books to get it right. Don’t expect to be remembered. Doing the right thing for the wrong reason really can be OK. Explore for the glory of doing it, for the experience of being part of something bigger than yourself. Explore for the difference it will make in the lives of people, perhaps your great great great grandchildren in five hundred years. Even if they won’t realize how much they owe you

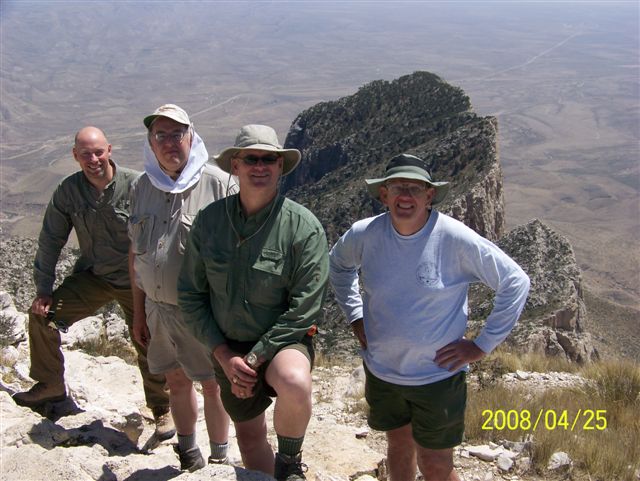

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to camp on a high shelf in the

There is a lot of exploring to do. It is just beginning. We should do it together with our friends. In peace. And if we do find somebody out there, we ought to treat them right.

And someday, when future generations read our memoirs, they will wonder what it was like to be among the very first to start on the voyage of discovery.

You old Conquistadors, they will envy you.

You see, in exploration you need to take the long view.