Once upon a time, not that long ago, people used to communicate by what were known as “letters.” These were written documents. Yes, actual hardcopy, paper items. And they were often transcribed by hand or, sometimes, generated on what was known as a “typewriter,” which was basically a manual, analog printer with no I/O port beyond direct keypad entry. These “letters” were sent to their intended recipients using a small denomination currency with an adhesive backing that is recognized for exchange by only one quasi-governmental agency.

I know that some of you may have doubts that people communicated with each other in primitive ways prior to email and text messages, but witness the cultural clues from the 1961 song illustrated above.

It was always believed that the toughest letter to receive was the dreaded “Dear John” letter (as in, “Dear John, I’ve fallen in love with someone else…”). However, I think t’at the hardest letter to write is the “it’s been awhile” letter. This one starts, “Well, it’s been awhile since I’ve written. Sorry.” This blog article is just like one of those letters. It’s been awhile since I’ve written one of these articles and I’m sorry about that. I could give you a big long list of all the really, really serious stuff that I’ve been doing instead, but that’s just a bunch of feeble excuses so I’ll keep them to myself. Instead, I’ll just get down to business and give you a status report on the J-2X development effort.

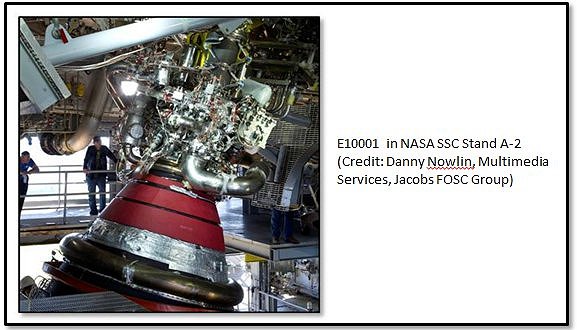

Engine #1 (E10001) Testing is Complete!

Over fourteen months and across the span of twenty-one tests, more than 2,700 seconds of engine run time was accumulated and recorded, including nearly 1,700 seconds of hot fire with an instrumented nozzle extension. With this engine we achieved stable 100% power level operation by the fourth test and full mission duration by the eighth test. While we don’t have any official statistics on the issue, most folks around here believe that we accomplished those milestones faster than has ever been done on a newly developed engine. We learned how to calibrate the engine and the sensitivities that the engine has to different calibration settings, i.e., orifice sizes and valve positions. We were able to estimate performance parameters for the full-configuration of the engine at vacuum conditions and the calculations suggest strongly that all requirements are met by this design and met with substantial margin. This is significant considering that we’ve long considered our performance goals to be pretty aggressive. Well, our little-engine-that-could showed us that it did just fine with those goals, thank you very much.

One of the truly unique and successful aspects of the E10001 testing was the testing of a nozzle extension. This component is a key feature that allows J-2X performance to far exceed that of the J-2 engine from the Apollo Program era. While it is true that we cannot test the full-length nozzle extension without a test stand that actively simulates altitude conditions, we did test a highly instrumented “stub” version that allowed us to characterize the thermal environments to which the nozzle is exposed during engine hot fire and it demonstrated the effectiveness and durability of the emissivity coating that was used. This stub-nozzle configuration is actually the current baseline for the in-development Space Launch System vehicle upper stage.

Another key success for E10001 was the demonstration of both primary and secondary power levels with starts and shutdowns from each power level and with smooth in-run transitions back and forth between them. That smoothness was thanks, in part, to demonstrating our understanding of the control of the engine. From the very first test it was clear that we understood pretty well how to control the engine in terms of proper control orifices for the various operating conditions. What we did not entirely understand — in other words the fine-tuning details — we successfully learned via trial-and-error throughout the E10001 test series. All of this learning has been fed back into further anchoring our analytical tools and models so that we can move forward with J-2X development with a great deal of confidence.

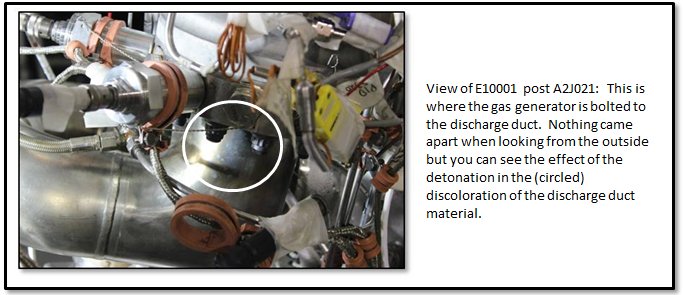

Okay, so that’s a brief description of just some of the good stuff. We had lots and lots of good stuff with the E10001 testing, far more than just that I’ve discussed here (see previous blog articles). The somewhat unfortunate part was the way in which the E10001 test series came to an end. On test A2J021, we had a disconnection between the intent for test and the detailed planning that led to the actual hardware configuration we ran for the test. That disconnection led to an ill-fated situation. Let me explain…

The J-2X gas generator has ports into which solid propellant igniters are installed. These igniters are like really high-powered Estes® rocket motors that light off when supplied with a high-energy electrical pulse. The flame from the igniter lights the fire of the hydrogen-oxygen mixture during the engine start sequence. It’s essentially the kindling for the fire of mainstage operation. The igniters perform this function at a very specific time during this sequence. If you try to light the fire too early, then you may not have enough propellant available in a combustible mixture so you get a sputtering fire. If you try to light too late, then you may have too much propellant built up such that rather than getting a good fire, you get an explosion instead. But here’s a key fact: You have to plug them in or they don’t work.

Have you ever stuck bread in the toaster, pushed down the plunger, gone off to make the coffee, and come back only to find that your darn toaster is broken? You curse a little because you’re already late for work and this is the last darn thing you need. You would think that somebody somewhere could make a toaster that lasts more than six months or a year or whatever. For goodness sake! We put a man on the moon and yet we can’t … oh, wait … um … ooops, it’s not plugged in. My bad.

In a nutshell, that’s what happened on test A2J021. The electronic ignition system sent the necessary pulse, but because of the uniqueness of our testing configuration as opposed to our flight configuration the wires carrying the pulse weren’t hooked up to the little solid propellant igniters in the gas generator. In the picture below you can see the external indication that something was not entirely good immediately after the test. The internal damage was more extensive to both the gas generator and the fuel turbopump turbine.

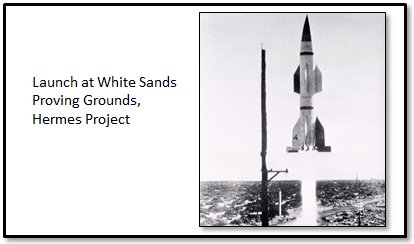

Many years ago, I met an elderly engineer who was still on the job well into his 80’s because he loved his work. His entire career had been dedicated to testing. He’d actually been there, out in the desert, in the 1940’s testing our very earliest rockets as part of the Hermes Project. One day, they had a mini disaster on the launch pad. He told me that the rocket basically just blew up where it sat. Boom and then a mess. And, it was his job to assemble the test report. Being a conscientious, ambitious, young engineer, he recorded the facts and offered a narrative abstract and extensive, annotated introduction that categorized the test as, well, a failure. Not long after submitting his report, one of the senior German engineers in the camp came into his office, put the test report down on the desk, and said that the tone of the report was entirely wrong. He said, “Every test report should begin with: ‘This test was a success because…'” The purpose of testing is to gather data and learn. If you learn something, then your test was, by definition, a success on some level. I’ve tried very hard to remember this very important bit of wisdom.

So, A2J021 was a success because we learned that we had some deficiencies in our pre-test checkout procedures. It was a success because it was an extraordinary stress test on the gas generator system. No, it didn’t recover and function properly, but neither did the engine come apart. While that might seem like a minor detail, when you’re hundred miles from the surface of the earth, you would much rather have a situation where an abort is possible than a failure that could result in collateral vehicle damage and make safe abort impossible. We have a stout design. Good. Also, this test failure was due to a unique ground test configuration. In flight, it’s not really plausible just because we would never fly in this configuration.

So, E10001 completed its test program with a bang. Kinda, sorta literally. But it was nearly the end of its design life anyway, so we didn’t lose too many test opportunities, and, as I said, even with test A2J021 the way it happened we learned a great deal. Overall, the E10001 test series was an outrageous success. Rocketdyne, the J-2X contractor, ought to be darn proud and so should the outstanding assembly and test crews at the NASA Stennis Space Center and our data analysts here at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. Bravo guys! Go J-2X!

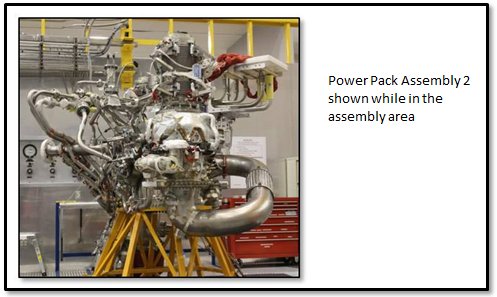

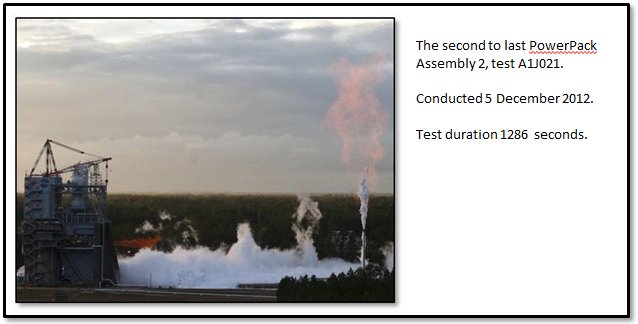

Power-Pack Assembly 2 (PPA-2) Testing is Complete!

Over ten months and across the span of thirteen tests, nearly 6,200 seconds of engine run time was accumulated and recorded on the J-2X Power Pack Assembly 2. That’s over 100 minutes of hot fire. Three of the tests were over 20 minutes long (plus one that clocked in at 19 minutes) and these represent the longest tests ever conducted at the NASA Stennis Space Center A-complex. But more than just length, it was the extraordinary complexity of the test profiles that truly sets the PPA-2 testing apart.

Because PPA-2 was not a full engine with the constraints imposed by the need to feed a stable main combustion chamber, and because we used electro-mechanical actuators on the engine-side valves and hydraulic actuators on the facility side valves, we could push the PPA-2 turbomachinery across broad ranges of operating conditions. These ranges represented extremes in boundary conditions and extremes in engine conditions and performance. On several occasions we intentionally searched out conditions that would result in a test cut just so that we could better understand our margins. As the saying goes: It’s only when you go too far do you truly learn just how far you can go. We successfully (and safely) applied that adage several times. In short, we gathered enough information to keep the turbomachinery and rotordynamics folks blissfully buried in data for months and months to come.

On an interesting and instructive side note, the PPA-2 testing also showed us that we needed to redesign a seal internal to the hydrogen turbopump. In the oxygen turbopump, you have an actively purged seal between the turbine side and the pump side. After all, during operation you have hydrogen-rich hot gas pushing through the turbine side and liquid oxygen going through the pump side. You obviously don’t want them to mix or the result could be catastrophic. That’s why we have a purged seal. But for the hydrogen turbopump you don’t have such an issue. During operation, at worst should the two sides mix you could get some leakage of hydrogen from the pump side into the turbine side that is already hydrogen rich. In order to maintain machine efficiency, you don’t want too much leakage, but a little is not catastrophic (and can be used constructively to cool the bearings). What could be dangerous at the vehicle level, however, is if you have too much hydrogen floating around prior to liftoff. This is especially true for an upper-stage engine like J-2X that’s typically sitting within an enclosed space until stage separation during the mission. You could have the engine sitting on the pad for hours chilling down and filling the cryogenic systems and you don’t want gobs and gobs of hydrogen leaking through the turbopump since any leakage ends up within the closed vehicle compartment housing the engine. That’s just asking for an explosion and a bad day.

To avoid this, within the J-2X hydrogen turbopump we have what is called a lift-off seal. And, as the name applies, it’s a seal that actively lifts off when we’re ready to run the engine. When the engine is just sitting there chilling down, not running, with liquid hydrogen filling the pump end of the hydrogen turbopump, the seal is, well, sealed. Then, when we’re ready to go, it unseals and allows the turbopump to operate nominally.

During the PPA-2 test series we found that we formed a small material failure within the actuation pieces for our lift-off seal. Then, upon analysis of the test data and a reassessment of the design, we figured out what was most likely the cause and Rocketdyne proposed a redesign to mitigate the issue. Again, going back to that important piece of wisdom: This testing was a success because, in part, we learned that we needed a slight redesign of the lift-off seal. That’s the whole purpose of development testing! Everything always looks great when it’s just in blueprints. It’s not until you hit the test stand do you truly learn what’s good and what need to be reconsidered. In the end, this sort of rigor and perseverance is what gives you a final product that you feel good about putting in a vehicle carrying humans in space. And that, truly, is what it’s all about.

As with E10001, the PPA-2 test series was simply an outrageous success. Rocketdyne should be proud and so should the outstanding assembly and test crews at the NASA Stennis Space Center and the data analysts at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. Bravo guys! Go J-2X!

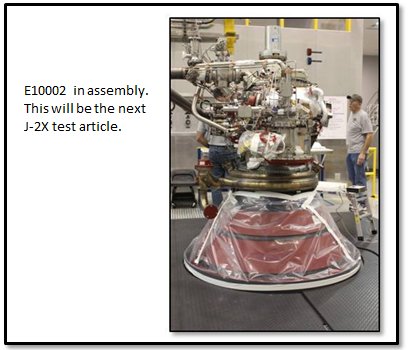

Engine #2 (E10002) Assembly is Underway

Our next star on the horizon is J-2X development Engine 10002. It is being assembled right now, as I’m typing this article. It is slated for assembly completion in January 2013 and it will be making lots of noise and very hot steam in the test stand soon after that. While our current plans are to first test E10002 in test stand A2, we will later be moving it to test stand A1. This, then, will be the first engine then to see both test stands. The more important reason for the A1 testing, however, is because that will give us the opportunity to hook up some big hydraulic actuators and gimbal the engine, i.e., make it rock and tilt as though it were being used to steer a vehicle. Now that will be some exciting video to post to the blog! I can’t wait.

Happy New Year!

So, this has been my “it’s been awhile” letter. Hopefully this will bring everyone up to speed with where we stand with J-2X development. In my next article, I will share with you some of what’s been keeping me from my J-2X article writing over the last several months. And, hopefully, it won’t be several months in the making. So, farewell for now and Happy New Year! On to 2013 and another great year full of J-2X successes. Go J-2X!