I love dictionaries (yes, I know, you’re shocked; shocked!). I have several at home and at work including a two-volume abridged Oxford English Dictionary (OED) that was a wonderful gift from my mother several years ago.

The definitions and word origin above comes from the OED on-line site. Embedded within our language is so much condensed history and accumulated knowledge that it’s amazing. While I have no doubt that this is true of every language, I only know my own to any significant degree. Indeed, I’ve been babbling my own language for a long time now — forty-some years — but I can always pick up a dictionary and learn something new with just the flick of a page or two. You really can’t say that about too many other things.

As the title for the article and the definitions above suggest, for this article we’re going to talk about “adaptation,” specifically about adaptation of the RS-25 engine. As part of the Space Launch System Program, we are undertaking something a bit unusual for the world of rocket engines. We are taking engines designed for one vehicle and finding a way to use them on another vehicle. Now, this is not a completely unique circumstance. The Soviets/Russians really were/are masters of this kind of thing. But for us, it is not something that we do very often. In terms of the big NASA program rocket engines, I can only think of the RL10 that was originally part of the Saturn I vehicle as an engine design that has had a long second and even third career on other vehicle systems. The truth is that engines and vehicles are, for us, generally a matched set and the reason is that we just don’t frequently enough build that many of either. Note that, technically speaking, we are also adapting the J-2X from a previous program, Constellation/Ares, but that’s obviously a bit different in scope and scale given where we are in the development cycle.

The name “RS-25” is, as I’ve mentioned in past articles, the generic name for the engine that everyone has known for years as the “SSME,” i.e., the Space Shuttle Main Engine. There is much to talk about the RS-25. Lots and lots of stuff. More stuff that I could possibly fit into a single article. Here are just some of the RS-25 topics that we’ll have to defer to future articles:

The name “RS-25” is, as I’ve mentioned in past articles, the generic name for the engine that everyone has known for years as the “SSME,” i.e., the Space Shuttle Main Engine. There is much to talk about the RS-25. Lots and lots of stuff. More stuff that I could possibly fit into a single article. Here are just some of the RS-25 topics that we’ll have to defer to future articles:

• History and evolution

• A tour of the schematic

• Engine control, performance, and capabilities

For this article, I want to just talk about the scope of work that will be necessary to adapt RS-25 to suit the Space Launch System Program.

Clear Communication

The most significant thing that has to be done to the RS-25 to make suitable for the new program is that it has to be able to respond to and talk to vehicle. Remember, the Space Shuttle was developed in the 1970s and first flown in the 1980s. Yes, many things were updated over the years, but given the lightning-fast speed of computer evolution and development, it is not surprising that what RS-25 is carrying around a controller basically can’t communicate with the system being developed today for the SLS vehicle. The SLS vehicle would say, “Commence purge sequence three,” and the engine would respond, “Like, hey dude, no duh, take a chill pill” and then do nothing (my lame imitation of 1980s slang as best I remember it).

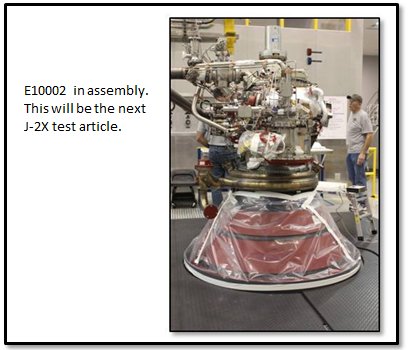

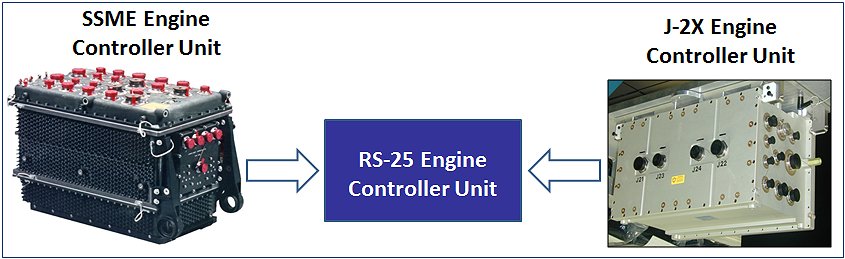

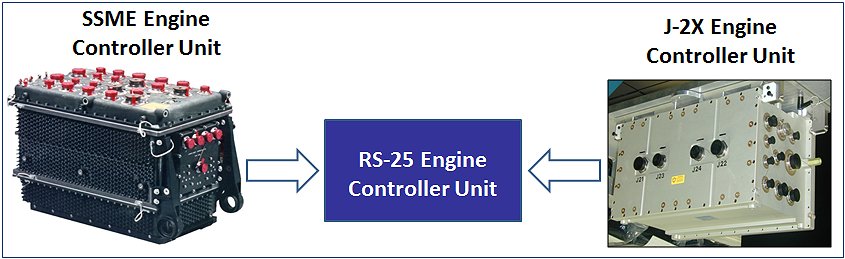

But here are the neato things that we’ll be able to do: We can use almost all of the work now completed on the J-2X engine controller hardware to inform the new RS-25 controller and we can use the exact same basic software algorithms from the SSME. Because the RS-25 has a different control scheme from the J-2X, we cannot use the exact controller unit design from J-2X, but we can use a lot of what we’ve learned over the past few years. And, because we can directly port over the basic control algorithms, we don’t have to re-validate these vital pieces from the ground up. We just have to validate their operation within the new controller. That’s a huge savings.

This is work that is happening right now, as I’m typing. Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne, the RS-25 developer and manufacturer, is working together with Honeywell International, the electronic controller developer, on this activity. Within the next couple of months, they will have progressed beyond the point of the critical design review for both the hardware and software.

In the long term, it is our hope that we will evolve to the utopian plain of having one universal engine controller, a “common engine controller,” that can be easily fitted to any engine, past, present, or future. Such a vision has in mind a standardization of methods and architecture such that we could largely minimize controller development efforts in the future to the accommodation of obsolescence issues. The simple truth is that development work is always expensive. It would be nice to avoid as much as that cost as possible. With the new RS-25 controller, we’re getting pretty close to that kind of situation.

Under Pressure

Have you ever spent much time thinking about water towers? As in, for instance, why are they towers in the first place? As you might have guessed, this is something that I wondered about many years ago as a pre-engineering spud. They seemed to be an awfully silly thing to build when you could just turn on the faucet and have water spurt out whenever you want. Ah, the wonderful simplicity of childhood logic: Things work just because they do and every day is Saturday.

have guessed, this is something that I wondered about many years ago as a pre-engineering spud. They seemed to be an awfully silly thing to build when you could just turn on the faucet and have water spurt out whenever you want. Ah, the wonderful simplicity of childhood logic: Things work just because they do and every day is Saturday.

The reason that you go to the trouble of sticking water way up in a tower is so that you have a reliable source of water pressure that can absorb the varying demands on the overall system. In the background, you can have a little pump going “chug, chug, chug” twenty-four hours per day pushing water all of the way up there, but by having this large, reserve quantity always in the tower, the system can respond with sufficient pressure when, at six in the morning, everyone in town happens to turn on the shower at the same time to start their day. The pressure comes from the elevation of tower, the height of the column of water from top to bottom.

On the Space Launch System vehicle we have something of a water tower situation except that, in this case, we’re dealing with liquid oxygen. In the picture below, you can see roughly scaled images of the Space Shuttle and the Block 2 Space Launch System vehicle. On both of these vehicles, the liquid oxygen tank is above the liquid hydrogen tank. This means that for the very tall SLS vehicle, the top of oxygen tank is approximately fifty feet higher relative to the inlet to the engines (as illustrated). This additional fifty feet of elevation translates to more pressure at the bottom just as if it were a taller water tower. However, in this case liquid oxygen is heavier than water (meaning more pressure) and the SLS vehicle will be flying, sometimes, at accelerations much higher than a water tower sitting still in the Earth’s gravitational field. Greater acceleration also amplifies the pressure seen by the engines at the bottom of the rocket.

“So what?” you’re saying to yourself as you read this. After all, higher pressure is a good thing, right? If you have more pressure at the inlet to the engine, then you don’t need as much pumping power. So, life should be easier for the engines with this longer, taller configuration. There are two reasons why this is not quite the case.

First, think about when the vehicle is sitting on the pad at the point of engine start. The pumps aren’t spinning so all the pressure you’re dealing with is coming from the propellant feed system. And now, simply, for the SLS vehicle it will be different than before. One of the tricky things about a staged-combustion engine, in general, is that the start sequence (i.e., the sequence of opening valves, igniting combustion, getting turbopumps spun up) is touchy. Given that the RS-25 has two separate pre-burners — and therefore three separate combustion zones — and four separate turbopumps, the RS-25 start sequence especially touchy. You have to maintain a very careful balance of combustion mixture ratios that allow things to light robustly, but not too hot, and a careful balance of pressures throughout the system so as to keep the flow headed in the right direction and keep the slow build to full power level as smooth as possible. We have an RS-25 start sequence that works for Space Shuttle. Now, for the SLS vehicle, we will have to modify it to adapt to these new conditions.

The second issue to overcome with regards to the longer vehicle configuration and the liquid oxygen inlet conditions is due total range of pressures that the engines have to accommodate. When sitting on the launch pad, you have the pressure generated by the acceleration of gravity. During flight, as you’re burning up and expelling propellants, the vehicle is getting lighter and lighter and you’re accelerating faster and faster, you can reach the equivalent of three or four times the acceleration of gravity. So that’s the top end pressure.

On the low end, you have the effect of when the boosters burn out and are ejected at approximately two minutes into flight. When this happens, the acceleration of the vehicle usually becomes less than the acceleration of gravity meaning that the propellant pressure at the bottom of the column of liquid oxygen can get pretty low. Momentarily, the vehicle seems to hang, almost seemingly falling, despite the fact that the RS-25 engines continue to fire. Pretty quickly, however, the process of picking up acceleration begins again. (In the movie Apollo 13, they illustrated a similar effect with the separation of the first and second stages of Saturn V. The astronauts are pushed back in their seats by the acceleration until, boom, first stage shutdown and separation happens and they’re effectively thrown forward. With the Space Shuttle and the SLS vehicle, however, the return to acceleration is not as abrupt as it was on Saturn V where they show the astronauts slammed back into their seats with the lighting of the second stage.) The point is that the RS-25 has to accommodate a very wide range of inlet pressures while maintaining a set thrust level and engine mixture ratio. While this has always been the case for the SSME/RS-25, the longer SLS vehicle configuration simply exacerbates the situation.

You’ll note that I’ve not talked about the liquid hydrogen here. That’s because, as I’ve mentioned in the past, liquid hydrogen is very, very light. Think of fat-free, artificial whipped cream. Yes, the top of the hydrogen tank is much higher, but due to the lightness of the liquid, it doesn’t make much difference at the engine inlet even when the vehicle is accelerating at several times the acceleration of gravity.

Some Like it…Insulated

Look again at the pictorial comparison of the Space Shuttle and the Space Launch System vehicles shown above. Do you see where the SSME/RS-25 engines are relative to the big boosters on the sides of the vehicles? On the Space Shuttle, the engines were on the Orbiter and they were forward of the booster nozzles. On the SLS vehicle, there is no Orbiter so the engines are right on the bottom of the tanks and their exit planes line up with the booster nozzle exit planes. In short, the engines are now closer to those great big, loud, powerful, and HOT boosters. We are in the process now of determining whether this poses any thermal environments issues for the RS-25. Thus far, based upon analyses to date, there do not appear to be any thermal issues that cannot be obviated through the judicious use of insulation.

Other environments also have to be checked such as the dynamic loads transmitted to the engine through the vehicle or the acoustic loads or whatever else is different for this vehicle. The point is not that all of these environments are necessarily worse than what they were on the Space Shuttle. It is only that they all need to be checked to make sure that our previous certification of the engine is still valid for all of these considerations.

The Tropic of Exploration

So those are the three most obvious and primary pieces of the RS-25 adaptation puzzle: a new engine controller, dealing with different propellant inlet conditions, and understanding the new vehicle and mission environments. Each of these pieces carries with it analysis and testing and the appropriate documentation so there is plenty of work scope to accomplish. We are extremely lucky to be starting with an engine of such extraordinary pedigree, performance, and flexibility.

Henry Miller once said, “Whatever there be of progress in life comes not through adaptation but through daring.” It is our intent to prove Mr. Miller wrong in this case. We will make progress by using the adaptation of RS-25 to enable the daring of our exploration mission.

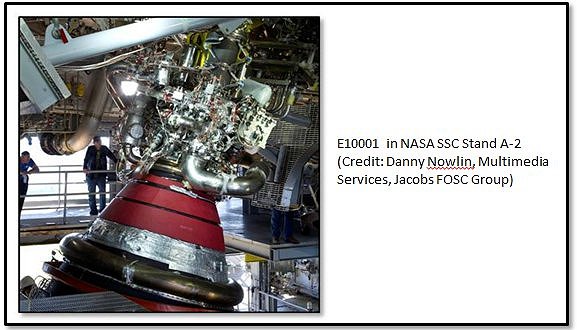

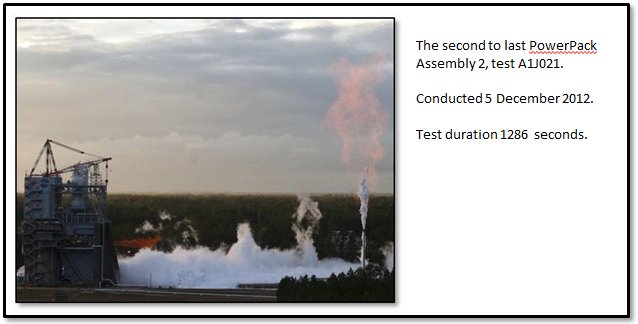

It was late in the evening and a little chilly. Though we’d arrived at the control center before dusk, test preparations had dragged on so that now darkness had enveloped the center. The test stand stood out against the blackened sky like a battleship docked in the distance. Brian, my team lead at the time with whom I’d driven down from Huntsville, and I were standing outside in the control room in the parking lot. The radiation from the hydrogen flair stack off to our left warmed one side of our face as the breeze cooled the opposite cheek. The wailing of the final warning sirens drifted off and all that could be heard was the burning torch of the flair stack and, in the distance, the low surging and gushing of water being pumped into the flame bucket. We were a just a couple of hundred yards from the stand.

It was late in the evening and a little chilly. Though we’d arrived at the control center before dusk, test preparations had dragged on so that now darkness had enveloped the center. The test stand stood out against the blackened sky like a battleship docked in the distance. Brian, my team lead at the time with whom I’d driven down from Huntsville, and I were standing outside in the control room in the parking lot. The radiation from the hydrogen flair stack off to our left warmed one side of our face as the breeze cooled the opposite cheek. The wailing of the final warning sirens drifted off and all that could be heard was the burning torch of the flair stack and, in the distance, the low surging and gushing of water being pumped into the flame bucket. We were a just a couple of hundred yards from the stand. First, there is the flash and then, quickly, the wave of noise swallows you where you stand. Unless you are there, you cannot appreciate the volume of the sound. It is not mechanical exactly. It is certainly not musical. It is not a howl or a screech. It is, rather, a rumble through your chest and a shattering roar and rattle through your head. You think instinctively to yourself that something this primal, this terrible must be tearing the night asunder; it surely must be destructive, like a savage crack of thunder that continues on and on without yielding. You are deafened to everything else, deprived of hearing because of all that you hear. Yet before your eyes there is the small yet piercing brightness of the engine nozzle exit that can just be seen on what you know to be deck 5 of the stand and, to the right, there are flashes of orange flame stabbing into the billowing exhaust clouds mounting to ten stories high, tinged rusty in the fluctuating shadows. It is like a bomb exploding continuously for eight minutes and yet the amazing thing, in incongruent fact so difficult to grasp as you are trying to absorb and appreciate the sensation is that the whole event is controlled and contained. You cannot believe that so much raw power can be expressed by what is only a distant dot within your field of vision.

First, there is the flash and then, quickly, the wave of noise swallows you where you stand. Unless you are there, you cannot appreciate the volume of the sound. It is not mechanical exactly. It is certainly not musical. It is not a howl or a screech. It is, rather, a rumble through your chest and a shattering roar and rattle through your head. You think instinctively to yourself that something this primal, this terrible must be tearing the night asunder; it surely must be destructive, like a savage crack of thunder that continues on and on without yielding. You are deafened to everything else, deprived of hearing because of all that you hear. Yet before your eyes there is the small yet piercing brightness of the engine nozzle exit that can just be seen on what you know to be deck 5 of the stand and, to the right, there are flashes of orange flame stabbing into the billowing exhaust clouds mounting to ten stories high, tinged rusty in the fluctuating shadows. It is like a bomb exploding continuously for eight minutes and yet the amazing thing, in incongruent fact so difficult to grasp as you are trying to absorb and appreciate the sensation is that the whole event is controlled and contained. You cannot believe that so much raw power can be expressed by what is only a distant dot within your field of vision.

The name “RS-25” is, as I’ve mentioned in past articles, the generic name for the engine that everyone has known for years as the “SSME,” i.e., the Space Shuttle Main Engine. There is much to talk about the RS-25. Lots and lots of stuff. More stuff that I could possibly fit into a single article. Here are just some of the RS-25 topics that we’ll have to defer to future articles:

The name “RS-25” is, as I’ve mentioned in past articles, the generic name for the engine that everyone has known for years as the “SSME,” i.e., the Space Shuttle Main Engine. There is much to talk about the RS-25. Lots and lots of stuff. More stuff that I could possibly fit into a single article. Here are just some of the RS-25 topics that we’ll have to defer to future articles:

have guessed, this is something that I wondered about many years ago as a pre-engineering spud. They seemed to be an awfully silly thing to build when you could just turn on the faucet and have water spurt out whenever you want. Ah, the wonderful simplicity of childhood logic: Things work just because they do and every day is Saturday.

have guessed, this is something that I wondered about many years ago as a pre-engineering spud. They seemed to be an awfully silly thing to build when you could just turn on the faucet and have water spurt out whenever you want. Ah, the wonderful simplicity of childhood logic: Things work just because they do and every day is Saturday.