If Murphy’s Law were actually true, things would arguably be much easier.

The old adage that “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong” has a reputation of being the apogee of pessimism, but think about how much simpler it would make things if it were true. Spaceflight is full of unknown possibilities, and if Murphy’s Law were really true, you’d only have to prepare for the worst of them.

It’s true for a college exam and it’s true in life or in engineering – it’s not the hard questions that will get you, it’s the ones you never imagined you’d be asked.

There’s a movie out now that captures the spirit of that. “The Martian” tells the story of Mark Watney, an astronaut on Mars who, to put it lightly, gets the opportunity to learn about what can go wrong in space exploration, and his survival depends on working with the NASA team back on Earth to answer questions none of them had ever imagined.

In many ways, “The Martian” is a spiritual successor to “Apollo 13,” both the 1995 movie and the 1970 NASA mission on which it was based. On that mission, a failure in an Apollo service module put the lives of the crew in jeopardy, and only through quick thinking, hard work and a lot of endurance was the crew able to survive.

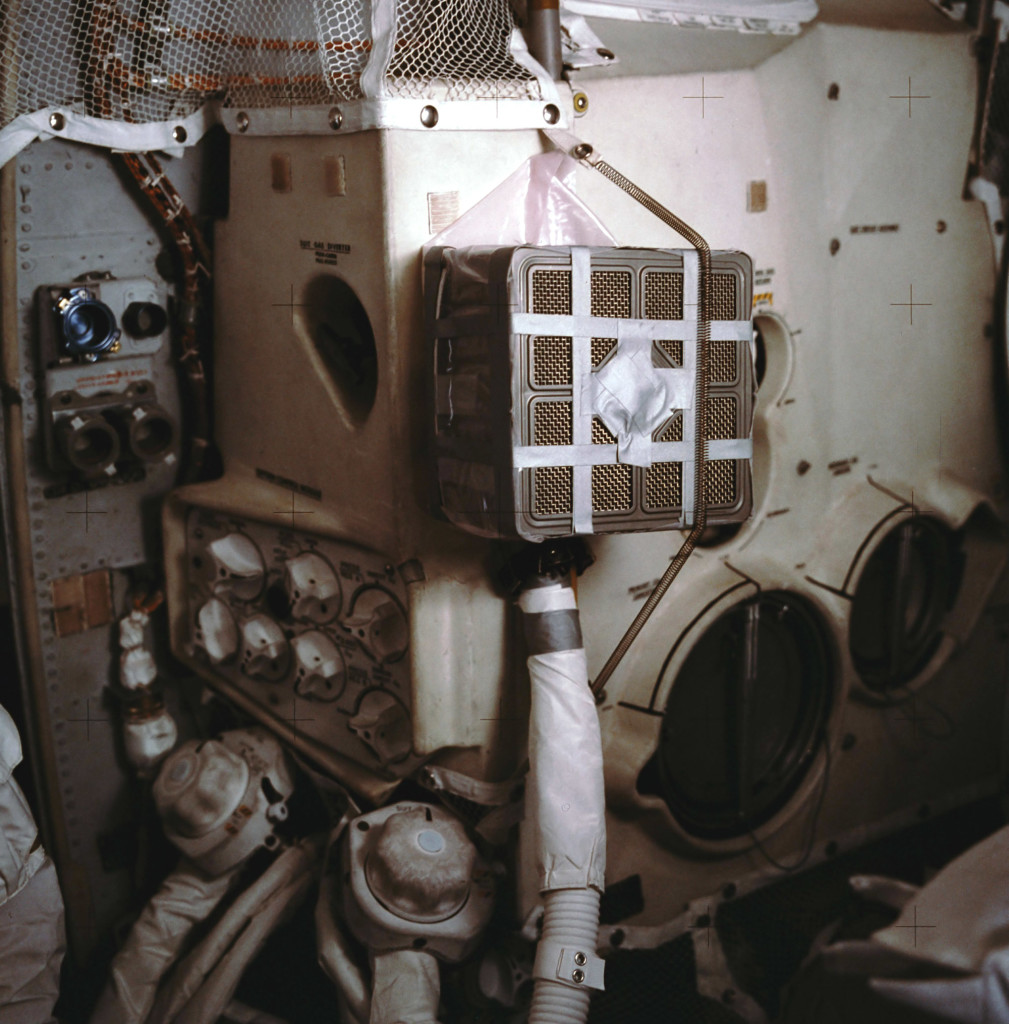

Both movies are edge-of-your-seat stories about the risks of spaceflight and the merits of duct tape, but while one is fiction and the other is based on a true story, they both are ultimately, in a very real way, stories about NASA — about who we are, and about how we rise to the challenge of answering those unexpected questions.

I’ve talked to engineers who have cited Apollo 13, both the mission and the movie, as something that inspired them to pursue engineering. There’s a scene in the movie where a collection of the items aboard the spacecraft are dumped on a table on Earth, and the engineering team is challenged to use them to figure out how to put a square peg in a round hole. More than one person has told me they saw that scene and said, “THAT’S what I want to do!”

The Apollo 13 mission has been described as being perhaps “NASA’s greatest moment.” I talked once with an astronaut who said this title should really go to a 10-day span in May 1973. When the Skylab space station launched on May 14, its first crew was supposed to follow it on the next day. An anomaly during launch caused the heat shield to be lost and the solar power system to be crippled, endangering the space station. In 10 days, NASA figured out multiple ways to save Skylab, designed and built two different solutions, and was able to launch the first crew on May 25. Apollo 13 was primarily a story of a crew and mission control, but the Skylab rescue was a nationwide effort.

You may never see a movie about the Skylab rescue. The world may pay more attention when lives – real or fictional – are in danger, but answering the unknown is something we do every day. When we do it successfully, it means that we prevent those lives from being endangered in the first place.

It made me happy that one of the first conversations I had with a coworker about “The Martian” wasn’t about what was right or wrong with the movie, but what could have been done differently to make sure the situation it depicts never happened in the first place. On a program developing a new vehicle, our job right now isn’t solving Apollo 13- or The Martian-style problems, it’s preventing them.

Which doesn’t mean we don’t have challenges on the Space Launch System program. We prepare for the worst and we prepare for the best and sometimes we get the unknown. A material doesn’t function in reality the way it does on paper. A proven system behaves differently in a new environment. And when that happens, just like in those movies, we roll up our sleeves and we find an answer to the unexpected question.

And the moments when we do, the moments you never see in movies when we make sure the next Apollo 13 never happens or the next Mark Watney is never stranded on Mars – THOSE are NASA’s greatest moments.

(For more about the Apollo 13 and Skylab rescues, along with other great “NASA Hacks,” check out this feature.)

Next Time: Who’s The Boss?

Join in the conversation: Visit our Facebook page to comment on the post about this blog. We’d love to hear your feedback!

David Hitt works in the strategic communications office of NASA’s Space Launch System Program. He began working in NASA Education at Marshall Space Flight Center in 2002, and is the author of two books on spaceflight history.