July 6, 2011

Don Perovich, a sea ice geophysicist at Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory in Hanover, N.H., is co-chief scientist for ICESCAPE. Perovich has studied sea ice for more than three decades, and more than two years of that time has been spent in the Arctic conducting field experiments. For ICESCAPE, Perovich directs the on-ice work. He is particularly interested in understanding how sunlight interacts with sea ice cover.

We talked with Perovich today after completing ICESCAPE’s third straight ice station. Here’s a look into what it’s like to be the “vice of ice.”

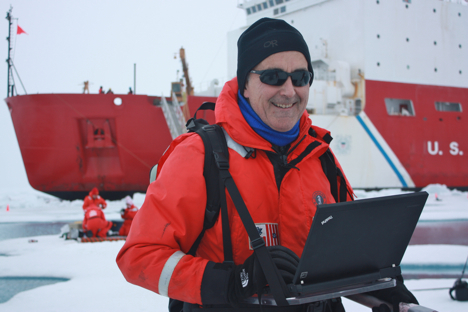

On July 6, 2011, Perovich prepared to take optical measurements during the field campaign’s third sea ice station. Credit: NASA/Kathryn Hansen

ICESCAPE: What’s the role of ICESCAPE’s co-chief scientist?

Perovich: If you look at it like a government, Kevin [Arrigo] is the president of ICESCAPE and I’m the vice president in charge of ice operations. So, in a way I’m the vice of ice.

My responsibilities have to do mainly with the ice stations. I help to select the ice floe, help to coordinate all of the ice activities, interface with the crew in terms of what we want to do on the ice, when we want to do it, how many people are going, and how long it’s going to take.

On the ice I have my own science to do and that is what’s really fun. Then, just to get a sense of what’s going on I go around on the ice and share treats — today it was chocolate chip cookies.

ICESCAPE: As the “vice of ice,” can you walk us through a typical ice station day?

Perovich: An ice station day really starts the day before when we’re in our 6:15 p.m. meeting and we decide that tomorrow is going to be an ice day. We found from our experiences last year that it works best if we pick a floe early, and so usually sometimes between 4 a.m. and 6 a.m. we select a floe that’s suitable for everybody and we park the ship.

Then, after breakfast it usually takes an hour or two to get ready for the ice station in terms of making sure all the batteries are charged, the generator is gassed up, all the gear is ready to go and prepositioned on the bow, so when its time to start we’re ready to go. At 10:30 a.m. we typically have a meeting on the bridge to discuss what we’re going to do, what the operation is going to be. That involves everybody who’s going on the ice and everybody supporting them. It can be a pretty big crowd.

Once that’s over it’s time for lunch. If we’re going to go on the ice for a few hours its nice to start off with a full stomach — that was easy to do today because we had macaroni and cheese. The macaroni and cheese is really good. And if that wasn’t enough we had peanut butter cookies to top it off. After all that eating and planning we actually go out on the ice and do some work!

Today we hit the ice around 12:30 p.m., broke into subgroups and spent three and a half hours on the ice making all sorts of measurements. At its best it’s an orchestrated ballroom dance with people swirling around doing different things. Some days it’s a little bit more like a mosh pit where everybody’s stomping around. Finally it’s time to wrap things up, leave the wonderful icescape and get back on board — just in time for dinner.

ICESCAPE: How does this year compare to last year?

Perovich: In a lot of ways, this year has been easier than last year. We’ve only done three stations [out of about ten planned] and my guess is that by the end the ice will be pretty sketchy. So far this year the three ice stations were all nice floes. We were heading north into an area covered by more than 90 percent ice that was about 3-4 feet thick, so there were lots of possibilities. Last year we were in some areas closer to the edge where sometimes it was hard to find the floe, or it was too thick and difficult to reach.

ICESCAPE: What makes a good floe?

Perovich: When we pick a floe, it’s good to step back and say ok, why are we here? The reason we’re here, what ICESCAPE is all about, is to understand how the changes in the physical environment and how changes in the sea ice cover are affecting the biology, the chemistry, and the ecology of the Chukchi and Beaufort seas. So we want to get ice that’s representative of this area and representative of changes. We’re looking for first-year ice — ice that formed this past winter. We want that kind of ice but not ice that’s deformed, not ice that has been pounded together and crunched into big fields of broken pieces of ice or piled up into large ridges. We want ice that’s nice and flat and representative of the area.

And then we want to have something that we can work on. That means we want to have some melt ponds — features where the meltwater collects on the surface that are anywhere from just a couple inches deep to a couple inches deeper than your boots are tall. Melt ponds are a very important feature and they affect sunlight, but we don’t want to have so many that it’s hard to go from point A to point B, because we want to be able to move around on the ice, at least in a limited way.

ICESCAPE: What, so far, are we seeing in the sea ice?

Perovich: We’ve gone 72 miles into the ice. That’s like going from a little bit south of Washington, D.C., to a little bit north of Baltimore, Md., so it’s not a huge distance. If you got in the car you could drive it in an hour. Over that distance the ice has gone from being just under 3 feet thick to 3.5 feet thick to now just over 4 feet thick. So the question is why? Of course we have theories that we have to confirm, but one possibility is the influence of the ocean melting the ice. As you get closer to the edge there’s more heat available to melt ice from the bottom and as you go further into the pack some of that heat’s already been used up.

Another thing we have seen, particularly at the first station where the ice was thinner, a lot of sunlight made it through the ice. About 40 percent of the sunlight coming down from the sky makes it through those melt ponds into the ocean where its available to either heat the ocean or provide energy for marine biota. So that’s not bad for just three days on the ice.

On July 6, 2011, Perovich used a spectroradiometer to measure the amount of sunlight reflected from the surface of the ice. Credit: NASA/Kathryn Hansen

ICESCAPE: You’ve been doing this sort of work for more than three decades … what inspires you to come back?

Perovich: When you go down the gangway onto the ice, even though you’ve done it at least hundreds maybe even a thousand times before, there’s still something special about it. As you can see from some of the pictures on this site, it’s a wonderland. It’s an area of incredible colors. Not many different colors, but blues and whites and some blacks. The ocean is as black as you can imagine, the ice is white and you see melt ponds in every shade of blue imaginable. Blocks that are upturned, some of those are white, some are grey, and some are incredible shades of blue. You go out and see new things all of the time.

When you’re in the working pack, it’s like real-time plate tectonics. You learn in school about how the earth has these giant plates that collide and over millions of years to form mountain ranges. In the ice, you can see it happen in 10 minutes; ice blocks that weigh as much as a car just get popped up into the air and fall back onto the ice.

ICESCAPE: What happens when the ICESCAPE fieldwork is over?

Perovich: Thanks to NASA for providing this wonderful opportunity to go on a mission to planet Earth, to the northernmost part. We’re lucky because ICESCAPE had two field seasons, we had a big field season last year and another one this year, but this is the last field season of the program and we have two years to make sense of the data. We’ll probably spend the first year working by ourselves figuring out our own data sets then the second year bring all the different components together to figure out how the system works.

One of the things we’ve learned is that the Arctic is a system. It’s not just ice over here, biology over there, chemistry someplace else; it’s really an intertwined system. So when the ship gets back to Seward I’ll be getting off and that will be the end of the ICESCAPE field experiments. But you can’t really stop doing these field experiments, there’s so much to learn. Even while we were here I submitted a proposal to come back a bit more north of where we are now, again to explore the changes that are going on in the Arctic. We want to be able to observe and understand those changes, in order to respond to those changes.

Ship Position at 2011/07/07 04:47:40

Long: 168 21.212 W Lat: 73 43.164 N

Terrific and informative post. Interviews of scientists are really interesting.

Approximately how fast is the ice melting in the area where you are? For example does it melt one inch in a week, 6 inches or a foot in a week? How fast does it melt in the center of the pack compared to near the edge? How thin can the floes get before they start to break up into small pieces?

Thanks for this post. I’d been wondering why some of the water in the Aloft Conn images was black and some was blue.

Don Perovich @ Michael Sweet: Great question. How fast the ice melts does depend on where you are. Today we at the ice edge and melting is fast due to the heat of the ocean. Lets look at some estimates for a few cases. Remember that ice melts both on the top and on the bottom.

Near the ice edge (was 5 feet thick in the beginning, melt season is 14 weeks long)

Top: 3 inches a week

Bottom: 15 inches a week

100 miles further north from the ice edge (was 5 feet thick before melt, melt season is 14 weeks long)

Top: 3 inches a week

Bottom: 3 inches a week

At the North Pole: (was 6 feet thick, melt season is 8 weeks long)

Top: 1 inch a week

Bottom: 1.5 inches per week

For more information of sea ice melting check out this web site:

http://imb.crrel.usace.army.mil/newdata.htm

And here is a question for you. Will the ice at these 3 locations survive the summer?

Don:

At the edge it will last 3 1/2 weeks so it will melt through and then you can go swimming 10 weeks later after it warms up. Too bad for the polar bears!!

At 100 miles in the thickness equals 60 inches and the rate is 6 inches per week so 10 weeks at that rate. It all melts. However, since the edge melted after 4 weeks, this becomes the edge and it would melt sooner than the estimated 10 weeks.

At the pole the rate is 2.5 inches per week for 8 weeks equals only 20 inches. This ice survives. But I note that the North Pole web cam shows extensive leads this year at the pole so bottom melt might increase- very unlikely to be enough to melt this ice in only 8 weeks. How long until the cam falls over?

Will the currents be enough to waft the North Pole ice into the Beaufort sea after the edge melts? (Or out the Fram strait) Can the multi-year ice in the Beaufort sea hold back the melt again this year?

Thanks for the answer. Good luck with your research.