by Anashe Bandari

In 2020, researchers using the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) announced they had discovered water on the sunlit surface of the Moon. Now, they’ve confirmed it – and found even more.

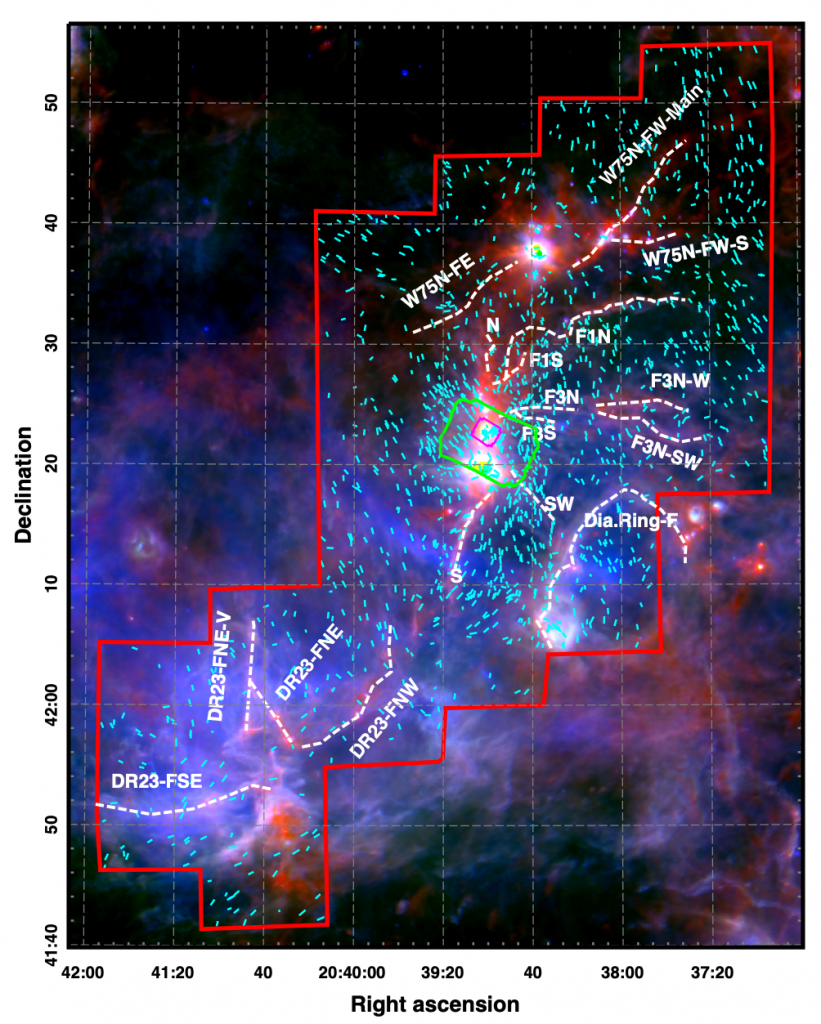

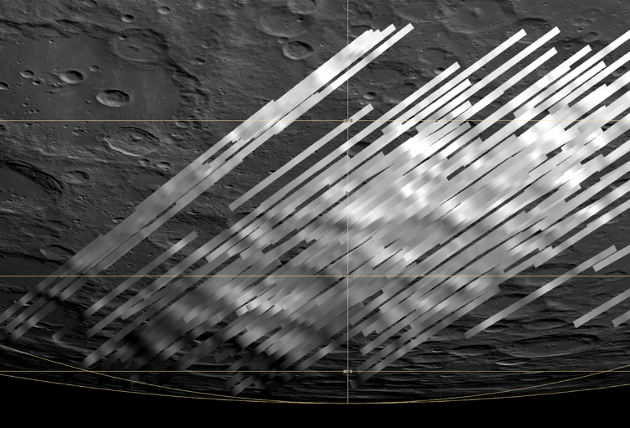

The team of researchers led by Casey Honniball, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, found molecular water in the Moretus Crater region, located near the Moon’s Clavius Crater, where the original finding took place. This confirmation that water is indeed present outside of Permanently Shadowed Regions on the Moon’s southern hemisphere allowed the researchers to begin decoding where this water comes from. Additionally, with the new observations, the researchers were able to create a map of the water abundances in the crater, which they could not do for the Clavius Crater due to insufficient data. Because the Moretus study included a much larger number of observations, the map helped determine that the abundance of water on the Moon varies with both temperature and latitude – in particular, there is more water at the poles and at lower temperatures.

“Water on the Moon is exciting because it allows us to study the processes that occur not only on the Moon, but also on other airless bodies. It is of extreme importance as a resource for human exploration,” said Honniball. “If you can find [sufficiently] large concentrations of water on the surface of the Moon – and learn how it’s being stored and what form it’s in – you can learn how to extract it and use it for breathable oxygen or rocket fuel for a more sustainable presence.”

When looking at the Moon, it is, in general, difficult to differentiate between water and hydroxyl – a molecule composed of oxygen bound to a single hydrogen atom (OH), as opposed to water’s two hydrogen atoms (H2O). With its Faint Object infraRed CAmera for the SOFIA Telescope (FORCAST), SOFIA can look at 6.1-micron emission features from the Moon, a wavelength of emission unique to water. And by flying above 99% of the water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere, SOFIA can see what ground-based telescopes cannot.

Because SOFIA is capable of distinguishing water from hydroxyl, the astronomers found evidence for a theory about how water came to be on the Moon in the first place, ruling out several previous hypotheses.

“The Moon is constantly being bombarded by solar wind, which is delivering hydrogen to the lunar surface,” Honniball said. “This hydrogen interacts with oxygen on the lunar surface to create hydroxyl.”

Then, when the Moon is hit by micrometeorites – which happens surprisingly often – the high temperature of the impact causes two hydroxyl molecules to combine, leaving behind a water molecule and an extra oxygen atom. A lot of this water is likely lost to space, while some is trapped within glass formed on the Moon’s surface by the impact.

More SOFIA data about lunar water is forthcoming: The group made additional observations to understand how water varies with the Moon’s latitude, composition, and temperature to corroborate the strong indications of increased water toward the poles in the current work.

NASA’s Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) will arrive on the South Pole of the Moon in late 2024 to map water in different forms and other volatiles. The SOFIA observations provide an idea of how one form of water is distributed in sunlit regions, helping to place VIPER’s future measurements into a broader context.

SOFIA is a joint project of NASA and the German Space Agency at DLR. DLR provides the telescope, scheduled aircraft maintenance, and other support for the mission. NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley manages the SOFIA program, science, and mission operations in cooperation with the Universities Space Research Association, headquartered in Columbia, Maryland, and the German SOFIA Institute at the University of Stuttgart. The aircraft is maintained and operated by NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center Building 703, in Palmdale, California. SOFIA achieved full operational capability in 2014, and the mission will conclude no later than Sept. 30, 2022. SOFIA will continue its regular operations until then.