When last I discussed with y’all the status of testing on the first J-2X development engine, E10001, I showed you a video of our first mainstage test, A2J003. That article was posted just over a month ago. So, what’s been happening since then? Hopefully, this brief article will catch you up to where we are.

First, we had test A2J004 in early August. This test went the full, planned duration of 7 seconds. This was our first test with any sustained duration at mainstage conditions. Lots and lots of good data. The Datadogs and the analysts were absolutely giddy for days and days afterwards.

We then had test A2J005 in mid August. This test was scheduled for 50 seconds duration but it was cut off at 32.2 seconds due to a not-totally-unexpected redline cut. This redline cut was similar to the one described for A2J003. In fact, it was the same parameter although the test conditions were different. You can stomp your foot, or kick at the air, moan, whine, whatever; it doesn’t really make any difference (…which is not to say that we did any of this … well, okay, maybe a little whining…). This is all simply part of the learning process with a new engine. It is expected, necessary, and educational. Deep breath and all is well.

Here is a video of test A2J005: J-2X Fifty Second Test

However, after test A2J005 shutdown — several seconds after shutdown — we had a “pop.” These are not uncommon when ground testing rocket engines so let me use yet another automobile analogy (since I use them so often) to explain.

Just a few years ago, I was still driving my 19-year-old pickup that I bought just before grad school. Towards the end of its long and glorious life, my little red truck developed a habit of rumbling and grumbling to a stop long after I’d turned the key to “off.” Residual gasoline fumes and air and hot metal combined into a sequence of “blurrr, blurrr, cough, cough, blurrr … POP” (and the neighbors just loved that!). In essence, a similar thing happened on A2J005.

In flight, the shutdown environments are quite different than on the ground. When you’re way, way up in the atmosphere — or even outside of the atmosphere — the surrounding environment is effectively a vacuum, which is a very useful means of sucking out any residual propellants from the engine after shutdown. On the ground, residual stuff (leftover propellants and fuel-rich combustion products) doesn’t get pulled out as efficiently. We can and do push it out with inert gas purges, but they’re not always as effective as we’d like. And so, on A2J005, we didn’t get everything pushed out as well as we’d like and we had a “pop” — or, actually, a “POP.” Technically speaking, it was a detonation in the “lox dome,” i.e., the oxidizer manifold volume feeding the main injector.

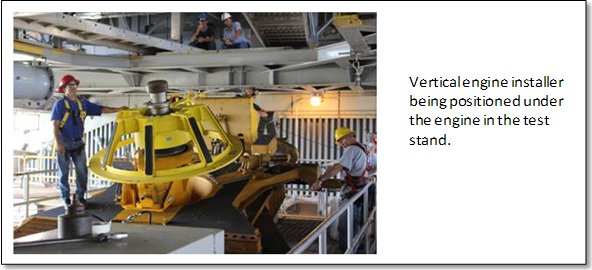

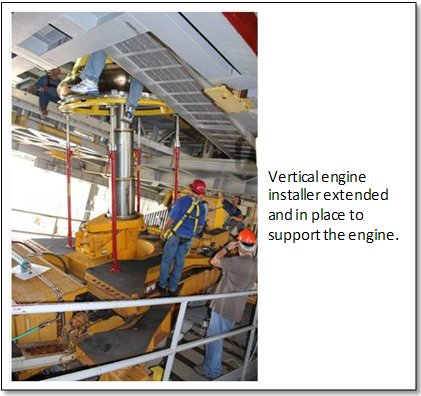

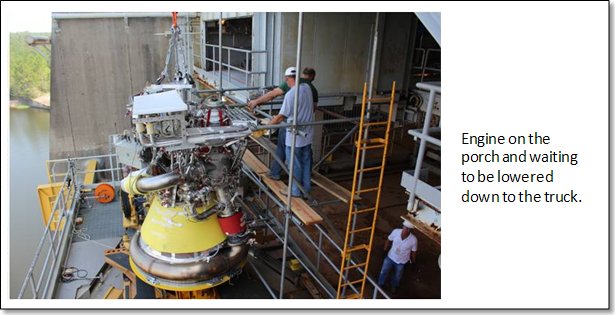

The bottom line is that we had some damage. It wasn’t anything that couldn’t be fixed and so, we’re fixing it. We didn’t bend any metal or anything like that. It’s more of breaking something that’s kind of like really tough plastic. Throughout this article you’ll see pictures of the engine being pulled out of the test stand because we couldn’t do the repair in place. After removal, we then took the engine back across the NASA Stennis Space Center to the assembly facility. In other words, we took it back to the garage for a tune up and we’ll be back in business soon. In fact, E10001 will be reinstalled by mid-September and we’ll be back into testing right around the start of October. Oh, and we’ll be doing a better job of avoiding pops based on what we’ve learned about purge rates and durations.

So, that’s where we stand. Two things to look forward to in the future: first, the upcoming report on test A2J006 after it happens, and, second, a discussion of another change we made to the engine while we had it in the shop. That latter discussion is an interesting technical tidbit regarding the internals of turbomachinery. So, “Don’t touch that dial!” and keep your set tuned to this station…

(I think that my grandparents had this exact set! Ahh, the good old days of vacuum tubes and horizontal hold.)

Thank you for the detailed update and explanations. Can you provide the actual dates the A2J001 through A2J005 took place?

Forgot to ask in my last post – can you tell us the date E10001 was removed and re-installed on the test stand? Thanks again!

Cool video. Will new high altitude engine test facility be ready in time to use for your J2X project?

@Tom

Test Dates:

A2J001 (chill test) – 7 July

A2J002 (burp test) – 14 July

A2J003 – 26 July

A2J004 – 5 August

A2J005 – 17 August

The engine was physically removed from the stand during the last week of August and was returned, ahead of schedule, just this week.

@Steve

Test Stand A3, the altitude-simulation stand, could be available to support J-2X development. Whether or not its usage is the most effective and efficient path is not entirely clear at the moment. With the formal announcement this morning of the Space Launch System, we will have to reevaluate our engine requirements and development plan.

Very good! Congratulations on the testing status. I remember the early days of testing on the SSME where there were some bad days during testing!

Dave

>>>>>>>>> Am confused – https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/j2x/j2x_ignition.html has “NASA conducted a combined chill test and 1.9-second ignition test July 14 of the next-generation J-2X rocket engine” and you have them listed separately. Could you please explain.

Test Dates:

A2J001 (chill test) – 7 July

A2J002 (burp test) – 14 July

A2J003 – 26 July

A2J004 – 5 August

A2J005 – 17 August

———————————————

>>>>>>>> Do you have the date of when work started (for removal) and ended (for re-install)?

The engine was physically removed from the stand during the last week of August and was returned, ahead of schedule, just this week.

Great Job guys – Back about 1965, I was assigned to monitor a few redlines for the first J2 engineering model. A redline was crossed so I hit the kill sw during the first test of the J2 at NAA S&ID SSFL’s Coco test stand A1 (the Battleship). That was the last time they allowed me to monitor charts during testing.

@Tom:

It’s just a matter of semantics. In truth, we do a chill test before every hot-fire, we just don’t call it that since it’s just part of the process for doing a test. They tied the NASA annoucement to the burp test and said that it was a chill and ignition test. It was. That was a true statement. But the chill part was a repeat of the first chill test A2J001. The public affairs folks didn’t release anything about the first chill test since, well, metal getting cold is not especially exciting (particularly if the test goes well and there are no unforeseen leaks and such).

In terms of getting the engine out of the stand and reinstalling it, either one takes a day. But, okay, that’s both the truth and an outright lie. Physically unbolting it, easing it down on the engine installer, loading it on the truck, and driving it to the assembly area can all be done in a day. That part is true. But safing the engine, drying the engine, disconnecting everything in an orderly fashion takes about a week. So we tested on the 17th and about a week later, after doing all these things, we physically removed it.

Getting it back in and getting it all hooked back up takes about two weeks all together. Yes, the physical installation only takes a day, but all of the fluid/gas connections have to be reestablished and every single one of those connections needs to be checked for leads. Then all of the electrical connections needs to be reestablished and every one of those needs to be checked out to make sure it’s operational. Given how much instrumentation we have on this development unit, that last part can seem like a mountain of work to accomplish. So, we drove the truck out there and jacked the engine back up into the test position just this past Monday the 12th. From there it will take about two weeks to get everything hooked back up.

Hope that helps.

Just read the SLS synopsis. Having an application for the J2X must be good news.

Cool. very.