Photo by Luke Trusel

From: Haley Smith Kingsland, Stanford University

66° 44’ 11 N, 163° 42’ 18 W, June 19 — Saturday night, fog obscured the sun and bathed members of the sea ice team in haze as they disembarked from the Healy to work on an ice floe off the port side. The group took multiple ice cores and water samples to learn about the biological activity and optical properties of ice. “It’s always nice to get to the first ice station,” said Don Perovich.

But choosing the right ice floe was tricky. The sea ice team spent the entire afternoon high up in the bridge — the observation deck where the captain navigates the Healy’s course — scouting ice floes in Kotzebue Sound with binoculars. “Because the area was mainly first-year ice undergoing quite a bit of melting, it was fairly fragile and would have been difficult to walk on,” said Don.

Keeping potential pieces straight posed a challenge for the team as well. “We kept saying, ‘It’s the white one! It’s the white one with a line!’” joked Chris Polashenski of Dartmouth. The group finally chose an ice floe that was different than the others: a thick piece of rafted ice, or two slabs on top of each other.

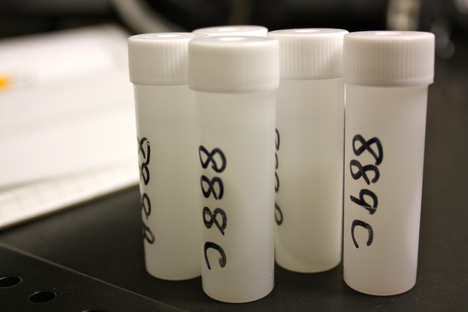

Later that night, the Coast Guard lowered a gangway from the Healy and the sea ice team spent nearly two hours on the ice. They used an ice core to drill through its entire thickness (seven feet!) while leaving intact an ice cylinder ten centimeters in diameter. They took four of these cores— one for Kevin Arrigo who will examine the biological activity in its different layers, two for Karen Frey who will conduct chemical analyses to measure the origin of the water, and one for Don who will study how light propagates through the ice as well as the thin microstructure of individual ice crystals. “The ice floe was shaking as we drilled through it,” said Luke Trusel of Clark University. “It was a little disconcerting.”

Next, the sea ice team deployed instruments down the holes left from the coring to take water samples. A layer of fresher water lies directly beneath sea ice, so these samples will allow scientists to measure how conditions under sea ice differ from those in the open ocean.

Studying sea ice at different stations by ship, rather than researching the same piece of sea ice throughout a melt season, will also allow scientists to consider variations between regions. Furthermore, they will be able to use sea ice data collected in the field during this ICESCAPE research cruise to check against data from satellites. “We want to relate what we see here with our own eyes to what the satellites are telling us,” Don said.

In early July, the sea ice team will have ten days of dedicated ice time in the Beaufort Sea. Soon a small group of scientists in orange jackets and red hard hats working on sea ice at twilight will become a common sight.

A gangway, or brow, brought the scientists down to the sea ice. (Photo by Parisa Nahavandi)

Photo by Parisa Nahavandi

Four members of the sea ice team and two Coast Guardsmen ventured out onto the sea ice. (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)

Don Perovich and Chris Polashenski start taking an ice core. (Photo by Haley Smith Kingsland)

Luke Trusel bags a section of ice core, which was cut into 10-centimeter layers before it melted. The chefs were cooking snacks just as the team came back aboard the Healy. “How unusual it was to be in the Arctic on an ice floe with the smell of brownies baking in the night!” Luke remembers. (Photo by Chris Polashenski)

The faint fog bow on the right is similar to a rainbow in terms of basic physics. “Raindrops are large enough to make colored rainbows, whereas fog droplets are too small and they make colors that smear together into white,” explains Bonnie Light of the University of Washington. (Photo by Luke Trusel)

Our icebreaker! “The crew did an impressive job parking a big ship on a small floe,” Don said. (Photo by Luke Trusel)