Our Soyuz spacesuit is named after the Russian word for falcon: сокол(sokol). It serves only one purpose, to keep us alive in the event of acockpit depressurization. We venture into a place that is devoid ofnearly all matter–a vacuum. This vacuum is as vast as space itself, andin a flash will remove our life-sustaining vapors with no moreperturbation than an 18-wheeler smashing a jackrabbit on Route 66. Andthe effect on your body would be about the same.

Our Soyuz spacesuit is named after the Russian word for falcon: сокол(sokol). It serves only one purpose, to keep us alive in the event of acockpit depressurization. We venture into a place that is devoid ofnearly all matter–a vacuum. This vacuum is as vast as space itself, andin a flash will remove our life-sustaining vapors with no moreperturbation than an 18-wheeler smashing a jackrabbit on Route 66. Andthe effect on your body would be about the same.

I have a symbiotic relationship with my spacesuit. I take care of it,and it takes care of me in return. Almost like a living exoskeleton, itcan take on its own cantankerous personality, and will bite, pinch, andtorque my flesh, leaving red pockmarks, bruises, pulled muscles, achingbacks, screaming knees, and occasionally a bleeding scratch or a blackfingernail (that slowly sloughs off like flesh in a sci-fi movie). Liketaming a wild animal, I’m aware of its nature, and I put up with anoccasional bite for the sheer pleasure of its company.

By design a space suit is hermetically sealed, so it creates amicroclimate that rapidly reaches 100% humidity at body temperatures. Wedo have cooling—a rather slow flow of air at tepid temperatures thatsweeps out some of the steamy vapor. If you just sit there, this coolingis adequate. We do have periods, particularly during emergencies, wherewe become quite active. During our training for fires (simulated withstage smoke), cockpit depressurization (simulated by inflating oursuits), and ocean landings (we practice the real thing in the BlackSea), the cooling system is deactivated and temperatures rise. Duringsome of these exercises, core body temperatures have reached over 39° C(102° F), requiring intervention from the array of flight surgeons whomonitor the exercise. During such exercises I have produced over 2kilograms (4½ pounds) of sweat, which ends up inside my sealedspacesuit. The suit thus becomes a mobile, living sauna. No wonder crewspractice the Russian tradition of sauna for off-duty relaxation—it’straining for the real thing.

My spacesuit is a marvel of fabric, polymers, and metal, custom-fitto my particular anatomy. It becomes a spacecraft in itself, shrunkendown to conform to the shape of my body. It is imperative to understandnot only where all the various levers, knobs, and closures are located,but also the engineering behind their operation. Every spacesuit has aregulator that senses the inside pressure so that it doesn’t drop below alevel required to maintain consciousness. NASA spacesuits use aregulator based on the difference in pressure between inside the suitand outside. Russian suits use a regulator based on absolute pressure.To a first order, this design is transparent to the user; the spacesuitssimply inflate when the ambient pressure drops. However, there arenuances that the user should keep in mind. Knowing the strengths andweaknesses of your pressure regulator will help you survive on a badday.

When dealing with technology in this wilderness, especially when it’srequired to keep one’s pink flesh safe, bad days can happen. Beware ofclaims for unsinkable ships. There were times when the U.S. and Russianspace agencies both dispensed with spacesuits. They were deemed anunnecessary expense. The engineering guaranteed that cockpitdepressurization could not happen. After both the U.S. and Russianprograms lost full crews, due in part to spacecraft depressurization,the spacesuits were brought back. Another lesson learned, pried from thebodies of those who explore.

When it comes time to doff my suit, I strip it off with a mix ofreverence (thank you for being there) and loathing (I can’t wait to getout of this thing). Like a moist, slimy worm emerging from a chrysalis, Ished this exoskeleton with great anticipation. Hot, sweat-soaked longunderwear steams in the cool air, and gives me needed relief fromevaporative cooling. This sensation is difficult to describe in words.

But our work is not done; we have to take care of our spacesuits. Ihook mine up to a ventilator, which inflates it like a large blowupdoll—or, more fitting, a blowup astronaut. It’s like we have visitingguests, perhaps company for dinner. It takes about 2½ hours to dry asuit. I do not want the inside of the suit to become a biologicalexperiment.

Thus I dote over my spacesuit with the same care a knight might takein preparing his battle armor. While still on Earth, I have an array ofsuit technicians, modern day squires, to help in the process. Thesepeople are experts, there to teach you the proper way to care for yourspacesuit, for there will come a day when you are on your own and haveto operate without any help. If you want to increase your chances tosurvive, it is imperative to absorb their pearls and become one withyour suit.

I hate my spacesuit; I love my spacesuit. Such contradictory thoughts remind me that I am very much alive.

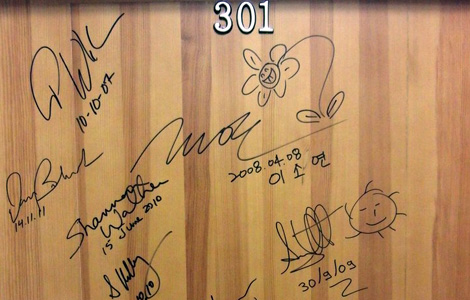

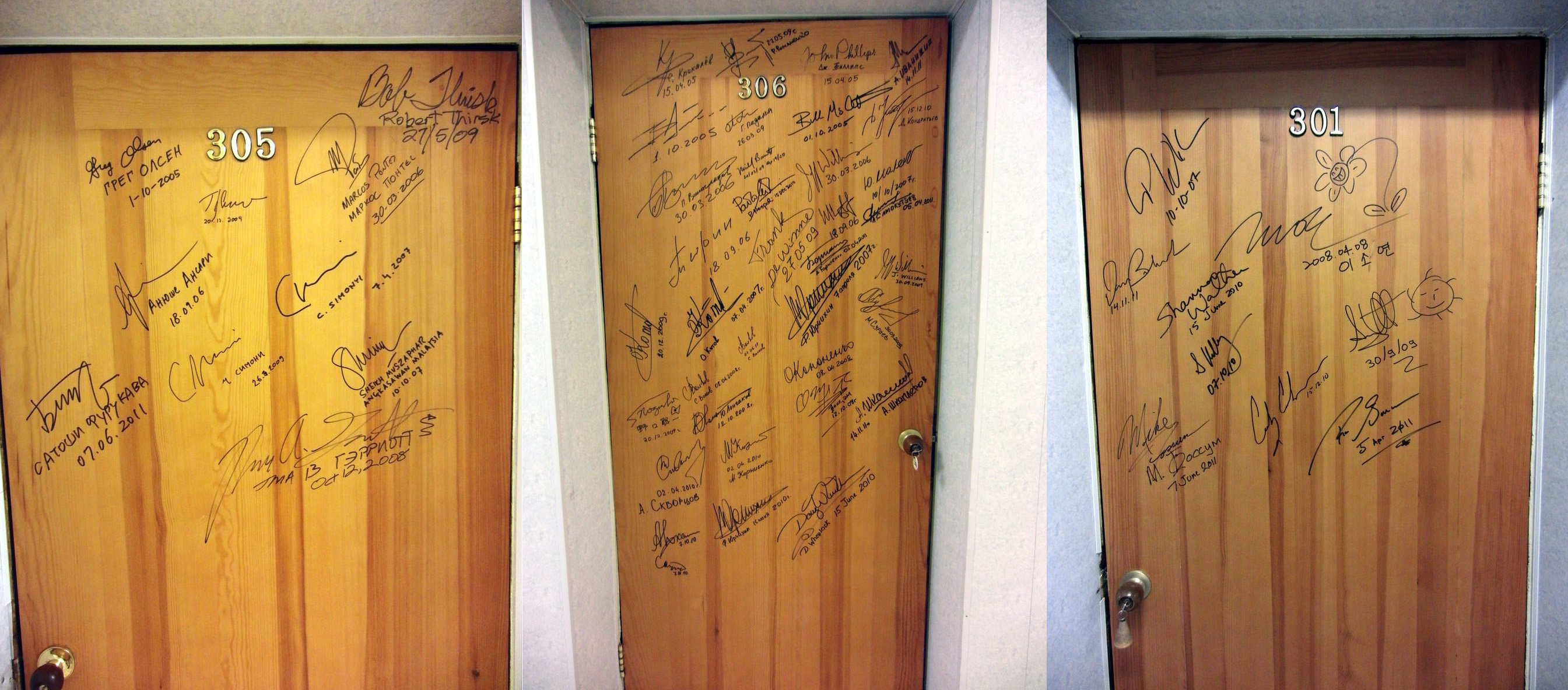

As you get closer to launch you shed earthly possessions, and your worldly stuff becomes meaningless. In my dorm room I give away my things, the tangible items needed on Earth that are of no use to me anymore. I shed the onerous chores of e-mail, phone calls, and mandatory web-based sensitivity training. I no longer worry about filling out my time card. None of this matters anymore. I am at the point where the only material things of concern are my spacesuit and rocket. A part of my heart, carefully barricaded into a small corner, is reserved for my family. As needed, I will allow such thoughts to fill me with strength.

As you get closer to launch you shed earthly possessions, and your worldly stuff becomes meaningless. In my dorm room I give away my things, the tangible items needed on Earth that are of no use to me anymore. I shed the onerous chores of e-mail, phone calls, and mandatory web-based sensitivity training. I no longer worry about filling out my time card. None of this matters anymore. I am at the point where the only material things of concern are my spacesuit and rocket. A part of my heart, carefully barricaded into a small corner, is reserved for my family. As needed, I will allow such thoughts to fill me with strength.

Our Soyuz spacesuit is named after the Russian word for falcon: сокол(sokol). It serves only one purpose, to keep us alive in the event of acockpit depressurization. We venture into a place that is devoid ofnearly all matter–a vacuum. This vacuum is as vast as space itself, andin a flash will remove our life-sustaining vapors with no moreperturbation than an 18-wheeler smashing a jackrabbit on Route 66. Andthe effect on your body would be about the same.

Our Soyuz spacesuit is named after the Russian word for falcon: сокол(sokol). It serves only one purpose, to keep us alive in the event of acockpit depressurization. We venture into a place that is devoid ofnearly all matter–a vacuum. This vacuum is as vast as space itself, andin a flash will remove our life-sustaining vapors with no moreperturbation than an 18-wheeler smashing a jackrabbit on Route 66. Andthe effect on your body would be about the same.