I enjoy the location of our hangar back home at Ames. Since it is one of the closest buildings to the runway and for that we get to watch a lot of air traffic flying in the area. We see the Blackhawks from 248, police helicopters, the H211 LLC airliners and Alpha Jet, also, the Zeppelin airship and the occasional F-18. I feel we have it pretty good back home. However none of it compares to the view from our “hangar” here at Ny-Alesund. While I’m performing the inspections in-between flights I can look out the roll up door and see a beautiful snow capped mountain. Take a few steps outside and you have a view of the entire fjords. Three glaciers that terminate in the water at the far end and handfuls more that don’t quite reach water are everywhere you turn. You can stop and watch the many research and cruise ships sail past or get out the binoculars and see what researches are doing at the cabin on the beach that is a half-mile down the cliffs. Our hangar here was actually built as a rocket assembly and launch control facility. The main work area is well sealed and has heat, which has been very nice on the particularly cold and windy days. The launch control room that we have been using as an office is built from solid concrete that we figure was designed to survive a failed rocket launch. Things have worked quite well in our home away from Ames aside from a few items plugged into 220v power that should not have been.

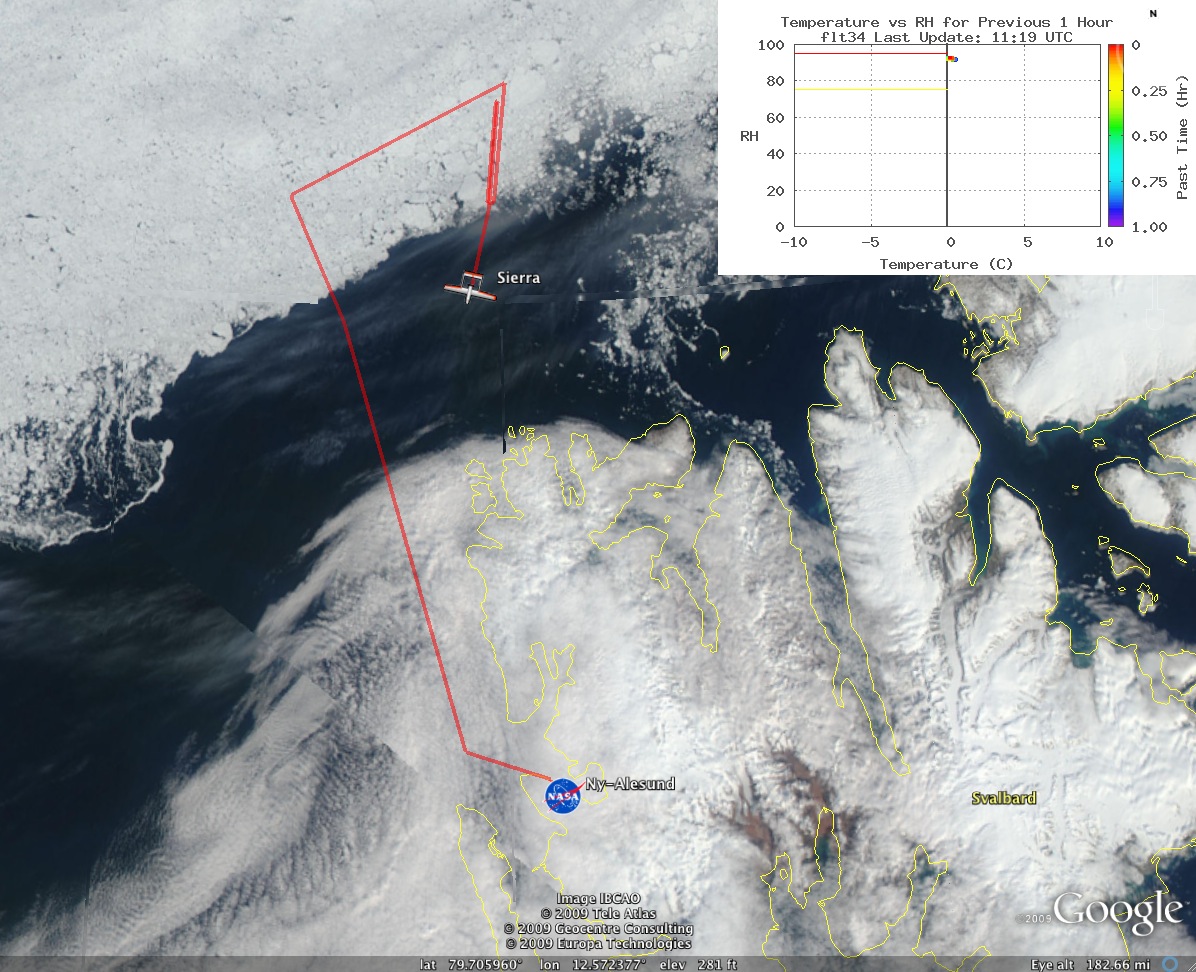

As for the operation of SIERRA things have gone mostly as expected. We had a few teething problems which was expected when operating such a young airplane in such harsh conditions. One operation item that we changed was to eliminate all taxiing. This has proven to reduce damage to the propeller because of small rocks kicked up by the exhaust and propeller. After the first inadvertent flight through clouds we sealed up the airplane much better. This added a little time on the runway for last minute sealing of seams but proved to help keep the insides dry. Speaking of the runway it can be cold and very windy. Most days after preflight of the airplane we had to perform a personal clothing preflight as well. This included wind proof pants and jacket plus gloves and a warm hat. After landing at the end of the day it was very easy to lose track of time while performing the post flight inspection because of the lack of darkness. There were multiple times that we walked out of the hangar after 11:00pm greeted by the shinning sun.

This has been a wonderful trip meeting new people and proving this aircraft as a valid platform. We flew a lot even having to ask for a flight extension. While we had some problems we overcame them in time to complete the mission. I will echo what others have said about the staff and facilities here. They are great people and we could not have dreamed of having such nice accommodations.

– Posted by Phil Schuyler, SIERRA crew chief

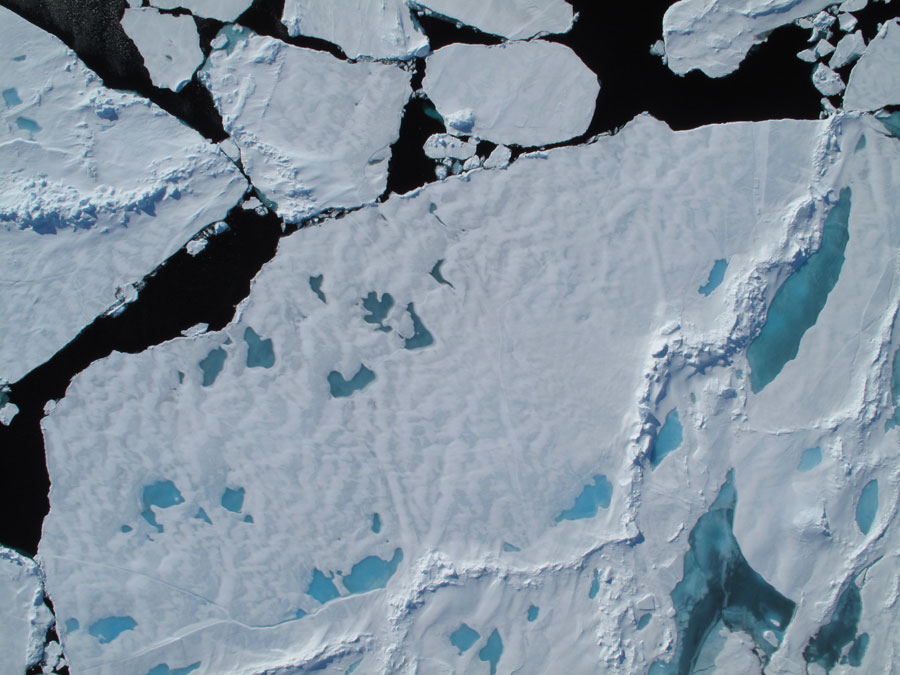

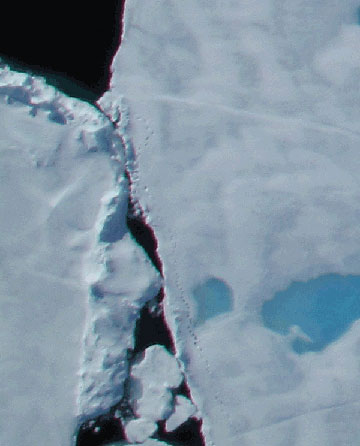

Spitsbergen Island in the summer

Spitsbergen Island in the summer