It wasn’t too many years ago that there was this thing about asking sports heroes after winning the big game, “So, what’s next?” They would always dutifully answer “I’m going to Disney World!” I guess that that whole thing is passé since I’ve not heard it in awhile, so I am going offer an alternative. Maybe it’ll catch on and be the BIG THING this summer…

…or, well, maybe not.

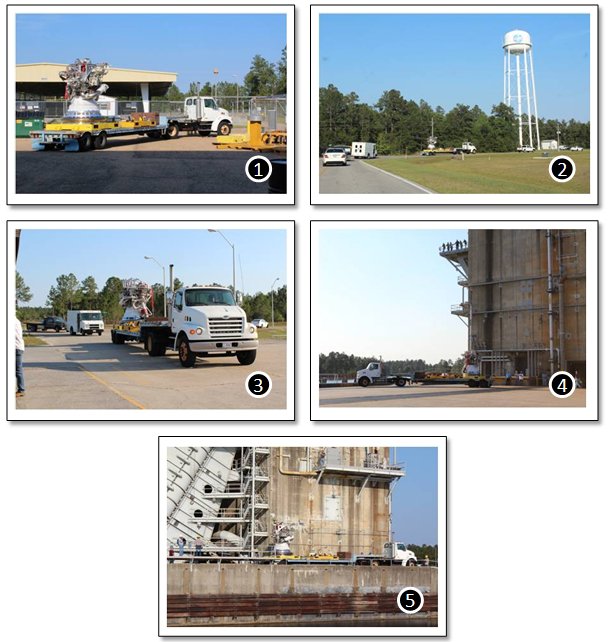

But that is what happens next. Our little engine is pulled out of the air-conditioned confines of its assembly area and trucked across the NASA Stennis Space Center to its test stand. No more pleasantly cool and dry air for you, E10001. This is Mississippi in June. Thus, in order to make this trip out in the open like this on the back of the truck (don’t try this at home!), the engine has to be sealed up tight against the humidity (and bugs) hanging in the air. Anywhere where there is an opening, there is a cover, a closure, or a plug. From the lot at the assembly building in picture (1) below, down the road towards the engine testing area in pictures (2) and (3), and finally arriving at the lot behind test stand A-2 in picture (4). In picture (5), you can see that the truck backs in alongside the test stand for the next operation.

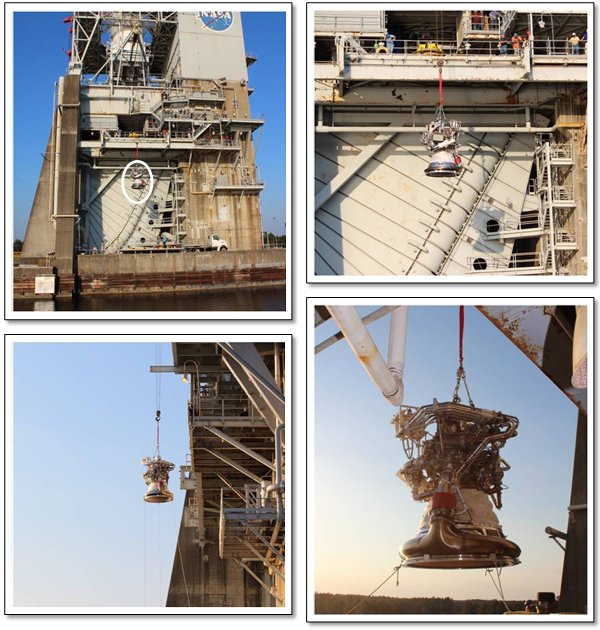

The next operation is to get the engine up into the test stand. Years ago, this test stand was built for testing the Apollo Program S-II stage (the second stage of the Saturn V vehicle that was powered by five J-2 engines). Back then, they basically picked up the whole stage (from a canal barge, not a flatbed truck) high into the air and lowered it down from above into the stand. When it was converted to be an engine-only test stand for Space Shuttle Main Engine testing in the early 1970’s, propellant tanks were added on top of the stand. So you can no longer lower the test article in from way up above. Rather, you lift it up about four or five stories and then pull it in laterally. This is the “engine deck,” the level where the engine will be installed into the stand. In the pictures below you can see the operation of pulling the engine off the transport truck and up to the engine deck level of test stand A-2.

After the engine is lifted to the correct height, it is brought laterally into the stand and set down on the “porch.” That’s what the folks on the test stand call it: the porch. The other day somebody (obviously from out of town) mistakenly referred to it as the “veranda.” We’ll have none of that fancy talk around here! The thing onto which the engine is set is the Engine Vertical Installer (EVI). This is a hydraulic lift table that will be used to raise the engine into place when it is to be bolted to the test stand. So, here is the sequence: you lift the engine up to the engine deck level, you pull it into the stand and set the engine down on the EVI sitting on the porch, then you slide the EVI horizontally into the heart of the test stand (the EVI is on rails for this purpose), you then raise the engine into the test position, bolt it in place, and then you slide the EVI back out of the way. Ta-da! Now you’ve installed an engine for test!

In the pictures below you can see the technicians positioning the engine onto the EVI on the porch. In the bottom picture of the set, you can see in the background to the left test stand A-3 still under construction and, to the right, test stand A-1 where, early next year, J-2X powerpack testing will be conducted.

So, our little baby engine is all grown up and ready to see the great big world from high up in the test stand. The next phase of our development program is now begun: the testing phase. After the engine is installed and the test stand is readied for hot fire, J-2X development engine E10001 will be used to demonstrate basic operations such as start, mainstage, and shutdown, to verify main chamber combustion stability, and to provide initial validation of numerous systems-level simulations and models.

Okay, somebody go carefully poke the Datadogs because soon we’re going to have genuine, full-up rocket engine test data from J-2X. And, as a final note, I offer an extra special tip of the hat to all of the folks at SSC (NASA, Pratt & Whitney, and support contractors) for doing an amazing job in terms of engine assembly and test stand readiness preparations. Don’t ever think that your extraordinary efforts go unrecognized or unappreciated. Bravo!

Outstanding! 🙂 So how slow was that truck moving? 1, maybe 2 mph? 🙂

Will we get to see pictures and video of the testing?

Test instrumentation makes it look a lot more complicated than the original J-2. No-one has ever described all the differences between the J-2 & J-2x. Can only gather that the gas generator exhaust pipe is made by printing. It uses some ball valves instead of butterfly valves. The combustion chamber is a channel wall instead of tubes. Maybe the electronics are newer.

Our impression is that a huge amount of time & money was spent making it incrementally safer, more powerful, & cheaper than the J-2, but it is not the leap that the SSME achieved, in a lot less time & probably the same amount of money. Still remarkable that no-one else in the world can afford to develop a cryogenic engine, yet not only can we afford one, but we can afford it despite the lack of a definite vehicle or mission.

Very cool. May we have bigger pictures please?

Thanks for the pictures and update on things. When will the testing begin? How many hotfires will this test article undergo? You mention in the tagline about the last image that the powerpack will be tested in A-1; will that testing be in conjunction with the J2X test firings or will it lead them or lag to await prelim results of the data from the hotfire?

Thank you for your hard work on getting this engine to the test stand in spite of the political uncertainty of the last seventeen months. Outstanding!

Great pictures! Hope the engine works ok.

@Aaron: Yes, you will get to see test pictures. However, be forewarned that we don’t always get good engine test pictures on test stand A-2. Over on A-1, the engine is just hanging out in the breeze (so to speak), so that’s where we’ve collected some of the more iconic images of SSME firing over the years, especially when we’ve had nighttime tests. Those are cool to see. But on A-2, because we have a passive diffuser and because for the initial series the exhaust will be enshrouded by a deluge of water spray, I’m not too sure how “rocket engine iconic” the pictures will be. We’ll do our best.

@JW: We expect that the first test of E10001 will happen before the end of June. It’s just a “burp” test to demonstrate successful chill and ignition. It’s an “all systems would have worked” check of the end-to-end system. We’ll be up and running mainstage tests in July.

The powerpack testing on A-1 ought to happen early next year. In order to deal with some programmatic issues, we pushed out the assembly of that test article until this autumn. However, the hardware, for the most part, is ready to go.

@guest: Please note that this is a development engine. It is not intended to fly. Ever. Development engines always look more of a “mess” than flight engines simply because we are collecting more data. The whole purpose of this development engine is to learn about what we’ve built. More data means more instrumentation and that means more mess.

I will address the whole J-2 vs. J-2X vs. SSME issue in the separate comment.

With regards to the issue of “huge amount of time and money” being spent, etc., I’d like to share just a few thoughts and words.

Unlike, say, plumbing supplies, we don’t stockpile rocket engines somewhere just waiting for installation here or there on some standardized system. Even if we’d wanted to build the old J-2 or J-2S, we could not have done it easily (please see an earlier blog article regarding a 1937 Ford pickup truck). And even if it had been easy, neither of those engines would have fulfilled the functional, performance, and safety requirements for J-2X or the array of imposed modern design standards.

Regarding SSME, please note that the study contracts for that engine began in the late 1960’s. It first tested in 1975. It first flew (with not-yet-fully-certified hardware) in 1981. It was a decade-long-plus overall development effort. And, beyond that, incremental development continued for another 20 years. I know since I worked on that project for many years. Any notion that the SSME we know and love so well today is the product of “a lot less time & probably the same amount of money” is mistaken by large factors – perhaps orders-of-magnitude factors.

Wow … really amazing to see this come together!