Editor’s note: This blog post was updated to include more information about the paper published in The Planetary Science Journal.

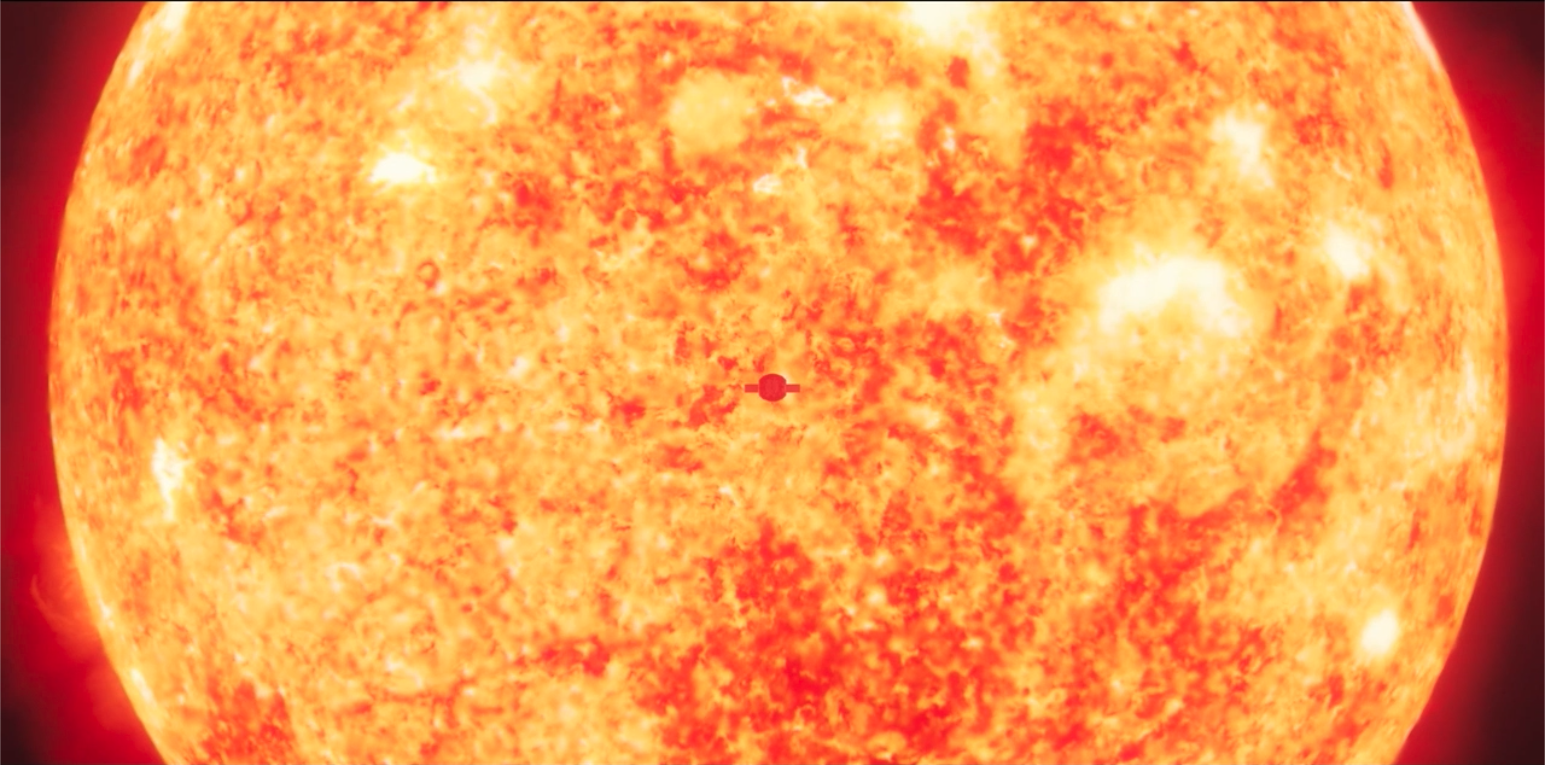

Each winter, the Geminid meteors light up the sky as they race past Earth, producing one of the most intense meteor showers in the night sky. Now, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe mission is providing new evidence that a violent, catastrophic event created the Geminids.

Most meteor showers come from comets, which are made of ice and dust. When a comet travels close to the Sun, the ice evaporates and releases gas, dislodging small pieces of the comet and creating a trail of dust. Slowly, this repeated process fills the comet’s orbit with material that produces a meteor shower when Earth passes through the stream.

However, the Geminid stream seems to originate from an asteroid – a chunk of rock and metal – called 3200 Phaethon. Asteroids like Phaethon are not typically affected by the Sun’s heat the way comets are, leaving scientists to wonder what caused the formation of Phaethon’s stream across the night sky.

“What’s really weird is that we know that Phaethon is an asteroid, but as it flies by the Sun, it seems to have some kind of temperature-driven activity. Most asteroids don’t do that,” said Jamey Szalay, a research scholar at Princeton University. Szalay was an author, with Wolf Cukier as the lead author, on the science paper recently published in The Planetary Science Journal.

The research builds on previous work by Szalay and several of his Parker Solar Probe mission colleagues, including the Geminids direct images captured by Karl Battams’ team, to assemble a picture of the structure and behavior of the large cloud of dust that swirls through the innermost solar system. Taking advantage of Parker’s flight path – an orbit that swings it just millions of miles from the Sun, closer than any spacecraft in history – the scientists were able to get the best direct look yet at the dust grains shed from passing comets and asteroids.

Built and operated by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, Parker Solar Probe does not carry a dedicated dust counter that would give it accurate readings on grain mass, composition, speed, and direction. However, dust grains pelt the spacecraft along its path, and the high-speed impacts create unique electrical signals, or plasma clouds. These impact clouds produce unique electrical signals that are picked up by several sensors on the probe’s FIELDS instrument, which measures electric and magnetic fields near the Sun.

To learn about the origin of the Geminid stream, the scientists used this Parker data to model three possible formation scenarios, and then compared these models to existing models created from Earth-based observations. They found that violent models were most consistent with the Parker data. This means it was likely that a sudden, powerful event – such as a high-speed collision with another body or a gaseous explosion, among other possibilities – that created the Geminid stream.

Parker Solar Probe is part of NASA’s Living with a Star program to explore aspects of the Sun-Earth system that directly affect life and society. The program is managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center for the Heliophysics Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. APL manages the Parker Solar Probe mission for NASA.

By Desiree Apodaca

Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD