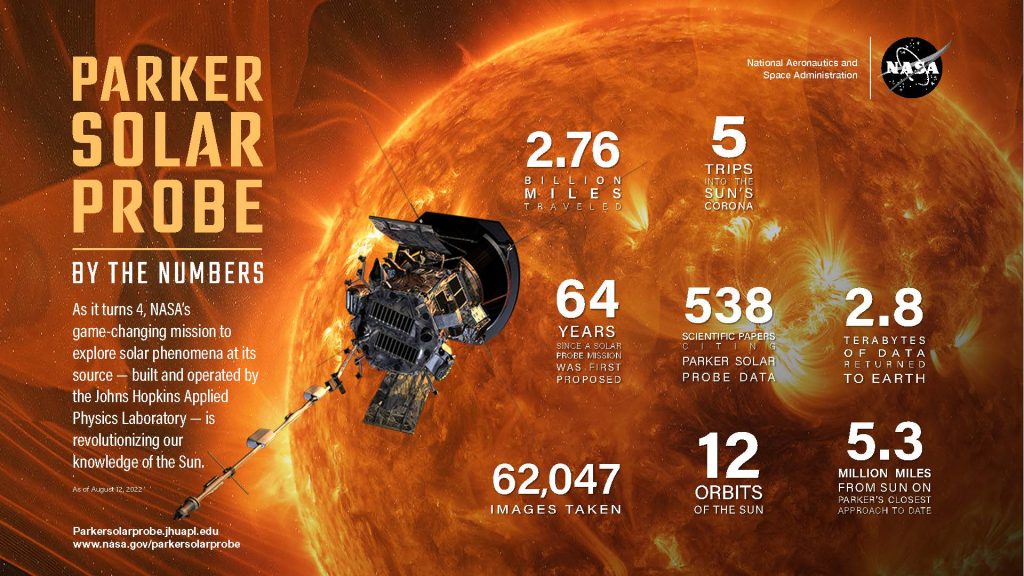

As NASA’s Parker Solar Probe approaches its 13th perihelion, or close encounter, with the Sun on Sept. 6, it is heading into a much different solar environment than ever before.

NASA reported earlier this summer that Solar Cycle 25 is already exceeding predictions for solar activity, even with solar maximum not to come for another three years. In recent days, a sunspot the size of Earth has rapidly developed on the Sun, and the star has given off multiple solar flares and geomagnetic storms.

“The Sun has changed completely since we launched Parker Solar Probe during solar minimum when it was very quiet,” said Nour Raouafi, Parker Solar Probe project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. “When the Sun changes, it also changes the environment around it. The activity at this time is way higher than we expected.”

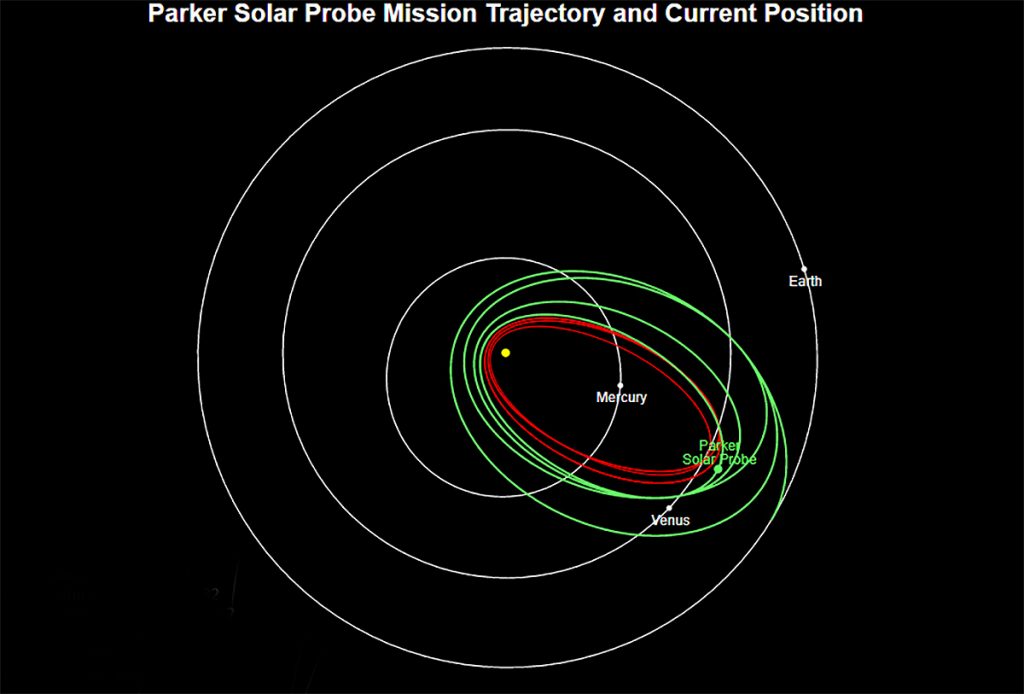

Raouafi expects the high level of solar activity to continue as Parker approaches this perihelion, just 5.3 million miles from the Sun. The spacecraft has yet to fly through a solar event like a solar flare or a coronal mass ejection (CME) during one of its close encounters, but that may change this coming month. The resulting data would be groundbreaking.

“Nobody has ever flown through a solar event so close to the Sun before,” Raouafi said. “The data would be totally new, and we would definitely learn a lot from it.”

Though the spacecraft has not flown through a solar event, Parker’s Wide-field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR) instrument has imaged a small number of CMEs from a distance, including five during the spacecraft’s 10th encounter with the Sun in November 2021. These observations have already led to unexpected discoveries about the structure of CMEs.

All of Parker’s observations aid in the effort to understand the physics of the Sun, helping better predict space weather, which can affect electric grids, communications and navigation systems, astronauts and satellites in space, and more.

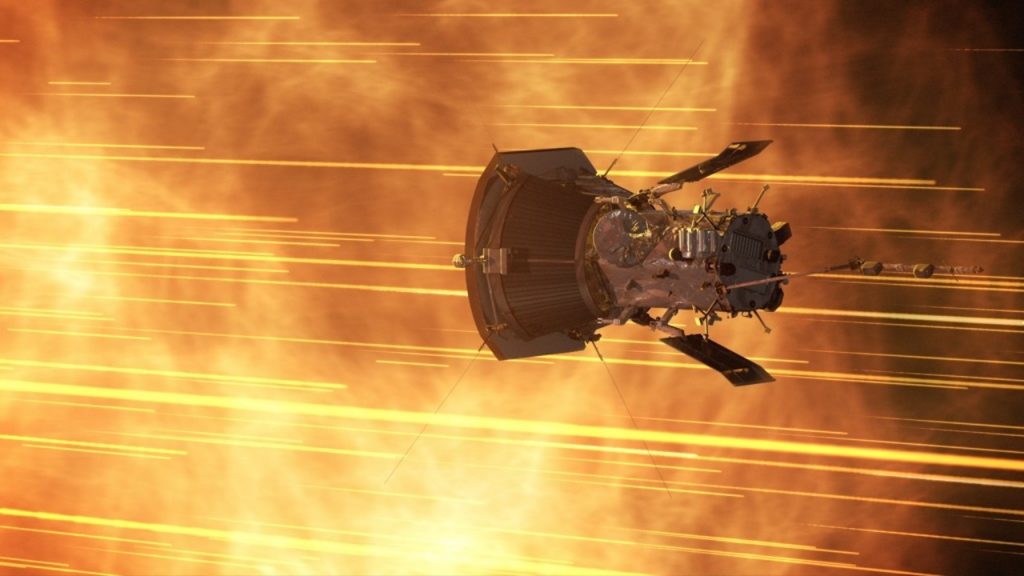

Although the Sun is much more active than during previous close encounters, Parker’s mission operators are not concerned about adverse effects to the spacecraft.

“Parker Solar Probe is built to withstand whatever the Sun can throw at it,” said Doug Rodgers, APL’s science operations center coordinator for the mission. “Every orbit is different, but the mission is a well-oiled machine at this point.”

While they will have very little contact with the spacecraft during its 10-day encounter, they have conducted routine operations to prepare, including readying the instruments, freeing up onboard memory space for new observations, and testing and pre-loading commands to operate the spacecraft while it’s out of contact. They have also coordinated observation times with Solar Orbiter, an ESA (European Space Agency)/NASA mission that will view the Sun from the same angle as Parker, but 58.5 million miles farther from the Sun’s surface.

Parker’s observations do not always overlap with those of other observatories, such as Solar Orbiter or Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory-A (STEREO-A), another NASA solar probe. But when they do, it offers significant advantages.

“By combining the data from multiple space missions and even ground observatories, we can understand the bigger picture,” Raouafi said. “In this case, with both Parker and Solar Orbiter observing the Sun from different distances, we will be able to study the evolution of the solar wind, gathering data as it passes one spacecraft and then the other.”

This is not the first time Parker and Solar Orbiter have been in alignment for one of Parker’s perihelions. Scientists have used data from previous alignments of the two spacecraft to produce multiple peer-reviewed papers on solar phenomena observed by both missions.

While this perihelion promises to be exciting due to high solar activity, Raouafi is already looking ahead to future close encounters.

“While the Sun was quiet, we did three years of great science,” he said. “But our view of the solar wind and the corona will be totally different now, and we’re very curious to see what we’ll learn next.”

Parker Solar Probe is part of NASA’s Living with a Star program to explore aspects of the Sun-Earth system that directly affect life and society. The Living with a Star program is managed by the agency’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Johns Hopkins APL designed, built, and operates the spacecraft.

By Ashley Hume

Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab