Propelled by a midsummer flyby of Venus, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has started yet another record-setting, science-gathering swing around the Sun, its sixth flyby of our star.

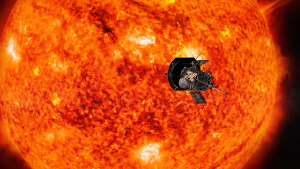

Some instruments on the spacecraft have been turned on since late August, collecting data on the near-Sun environment and the solar wind as it streams from our star. At closest approach (called perihelion) on Sept. 27, Parker Solar Probe will come within about 8.4 million miles (13.5 million kilometers) of the Sun’s surface while moving 289,927 miles per hour (466,592 kilometers per hour) — shattering its own records on both counts.

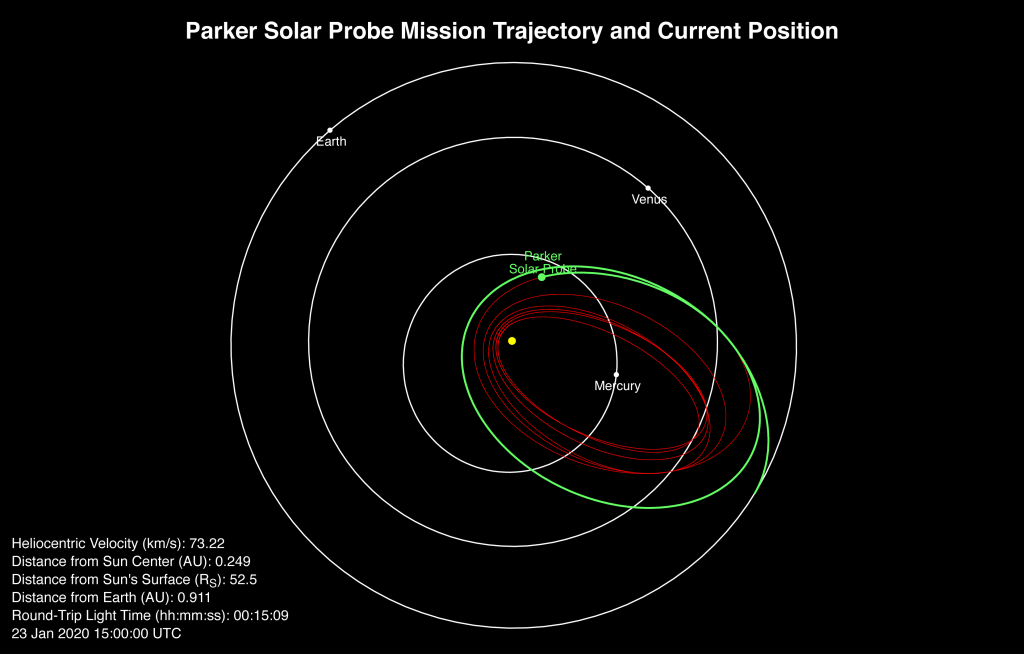

This also marks the first time Parker Solar Probe will dip to within 0.1 astronomical units of the Sun’s center; an “AU” is 93 million miles, the average distance between Earth and the Sun.

“After our last orbit — during which we started science operations much farther out than this encounter — we’re returning our focus to the solar wind closer to the Sun,” said Nour Raouafi, Parker Solar Probe project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “We always wonder if we’ll see something new as we get closer and closer. And as the solar cycle rises and the Sun becomes more active, we’ll be able to observe that activity from an unprecedented vantage point.”

Two years into its journey, Parker Solar Probe remains healthy and operating normally. As it continues its seven-year mission, the spacecraft will eventually travel within 4 million miles of the Sun’s extremely hot surface. The mission’s primary goal is to provide new data on solar activity and the workings of the Sun’s outer atmosphere — the corona — which contributes significantly to our ability to forecast major space weather events that impact life on Earth.

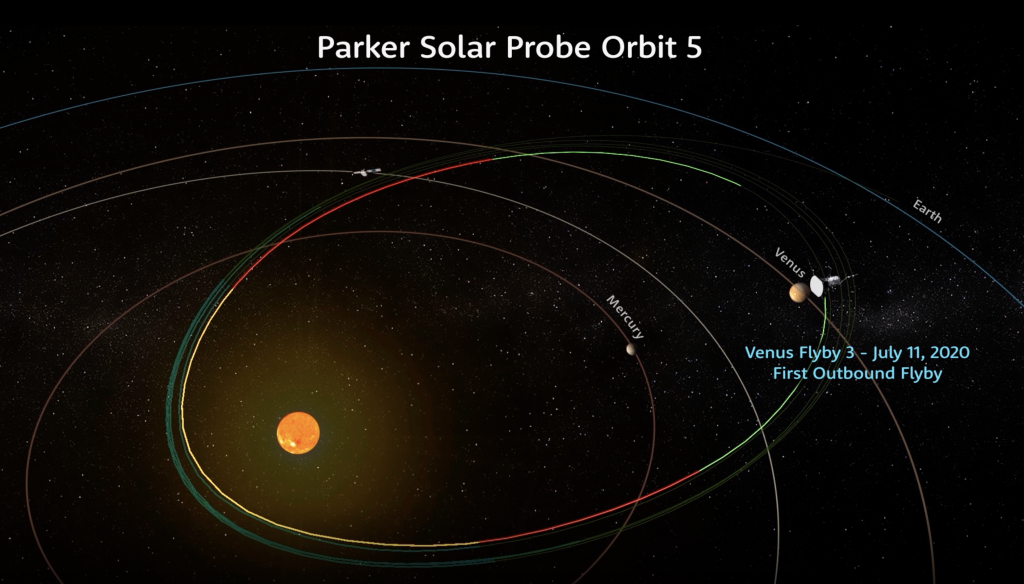

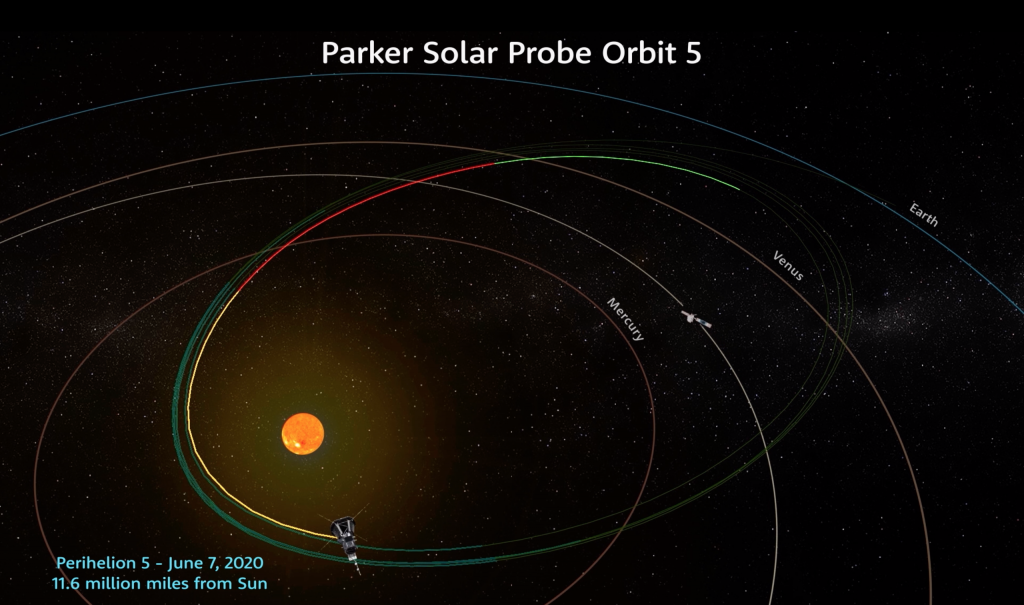

This weekend’s perihelion was set up by the probe’s third Venus flyby. On July 11, the spacecraft came within 518 miles above Venus’ surface — much lower than the previous two flybys but still well above Venus’ atmosphere — putting it on a path that brings it 3.25 million miles closer to the Sun than the last perihelion, on June 7. Mission Design and Navigation Manager Yanping Guo of APL noted that the gravity assist provided the mission’s largest orbital speed reduction since launch, trimming the spacecraft’s velocity by 8,438 miles per hour (13,579 kilometers per hour).

Related: Watch how data travels from Parker Solar Probe to Earth.

By Mike Buckley

Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab