I’d like to introduce a special guest blogger this week, Martin Burkey. Martin is the SLS strategic communication team’s resident expert on all things engines. As we prepare for next week’s RS-25 engine testing event at Stennis Space Center – if you’re not already, follow @NASA_SLS on Twitter and our Facebook link below for more info – Martin will be filling in this week and next to talk about our engines and how we test them. — David

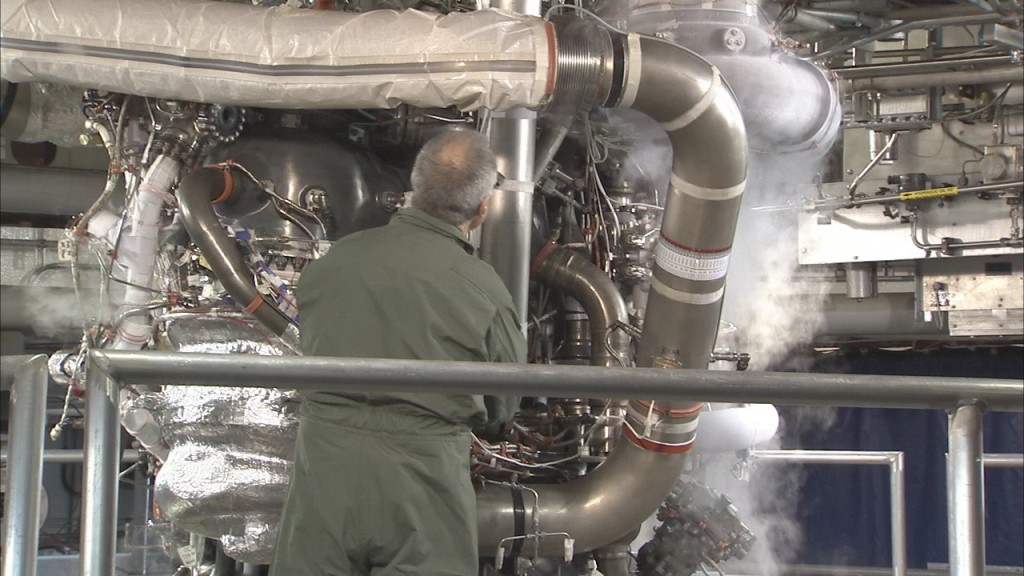

None of the test stands at NASA’s Stennis Space Center look anything like a spaceship. But they operate a lot like a spaceship, even though none of them will ever leave the ground.

A test stand is designed to make a fire-breathing rocket engine think it’s a spaceship, while at the same time keeping it from taking off for space the way it was made to. Those two requirements account for why test stands look and operate as they do… and why they aren’t as compact, light and sleek as a rocket.

Most of the big Stennis test stands were built in the 1960s to test Saturn rocket engines. Over the years, they’ve continued to serve the nation by testing Space Shuttle Main Engines and other government and commercial rocket engines. Today, the center is buzzing with test activities in support of NASA’s Space Launch System.

The A-1 Test Stand is the focus of testing to adapt the RS-25 –formerly known as the shuttle main engine – to new SLS performance requirements and environments. It will also be used to test engines with new components for the second SLS mission. The B-2 Test Stand is being readied to support testing of the massive 200-foot SLS core stage with its four RS-25 engines.

Thousands of tons of hulking, ungainly concrete and steel hundreds of feet above and dozens of feet below the Mississippi soil keep the engine locked in place for testing under way this year. An intricate network of tanks, pipes, cables and other equipment provides the engine with all the propellants, power, pressure, vacuum, fluids, cooling, data management and other services to – safely and accurately – simulate a full rocket mission from pre-launch preparations to nearly 200 miles in space.

Why test the RS-25, an engine that flew successfully for more than 3 decades and has over a million seconds of operating time? Because the RS-25 is a complex and finely tuned piece of equipment that requires thorough understanding various component interactions and responses under different conditions. Like other rocket engines, it operates at extremes of temperature, pressure, vibration, etc. that have to be monitored. More specifically, the RS-25 needs to be adapted to SLS requirements and environments such as higher propellant inlet pressure and lower temperature and integrates technology like a new engine controller unit. The test stand environment allows controlled testing of abnormal conditions and more thorough monitoring and observation than the flight environment. Ultimately, it’s better to find problems on the ground than in flight. There’s a saying in rocket testing – “Test like you fly, and fly like you test.” In other words, make the engine do everything on the ground it’s going to have to do in flight, and don’t do anything in flight you haven’t made the engine do on the ground. Why are we testing a proven engine? Because Space Launch System is going to make its RS-25s do new things in flight, but not until every one of them has been done successfully on the ground.

The A-1 stand supporting the current test series provides the RS-25 with liquid hydrogen (LH2) and oxygen (LOX) propellants. The stand has its own run tanks for propellants but they can also be filled from a 12-inch line running from LOX and LH barges docked near the test stand during test firing. The B test complex is also served by propellant barges, though stage testing relies on the propellant in the stage alone.

From a safe distance, the Stennis test stands look like crude, utilitarian structures. Up close, they are intricately woven with a network of pipes, cables, and other hardware designed to exercise rocket engines and extract the important data.

The stand provides various gases such as nitrogen and helium for drying, pressurizing and preventing premature combustion in the engine, as well as breathing air for crews working in the engine nozzle before and after testing.

The stand also provides hydraulic and pneumatic pressure to operate the engine propellant valves. There’s electrical power to run the engine controller. There are data cables that carry engine performance information to and from the engine and the vehicle computers and crew. The high speed data system has 186 channels that can record various conditions at more than 100,000 times per second. Four high-speed cameras can record 250 frames per second. Low-speed video includes infrared, black and white and color cameras.

And, of course, there’s water for fire suppression on the stand and water to cool the stand’s ubiquitous “flame bucket” that directs engine exhaust exiting the nozzle at thousands of degrees away from the stand where it rapidly condenses into steam and then into rain that falls downwind. The A-1 bucket consists of 21 slanted deflector segments that make up the deflector seen in pictures. Each segment gets pressurized water, and each segment is drilled with a specific number and pattern of holes that spray water and keep the deflector cool during test firing. During tests, the stand uses 170,000 gallons of water per minute from a nearby reservoir.

The “crew” of the A-1 stand consists of about 50 people, some on the stand until 30 minutes before a test and others in the hardened Test Control Center 200 yards away from the test stand.

So while rocket engine testing may not resemble any real or fictional spaceship, it’s still very much “rocket science” and a critical part of getting NASA’s next great exploration rocket to the launch pad.

Next Time: RS-25 Engines: Meeting the Need for Speed

Join in the conversation: Visit our Facebook page to comment on the post about this blog. We’d love to hear your feedback!