This week’s Rocketology post is by the newest member of the SLS communications team, Beverly Perry.

When NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) first flies, it will slice through Earth’s atmosphere, unshackling itself from gravity, and soar toward the heavens in an amazing display of shock and awe. To meet the engineering challenges such an incredible endeavor presents, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center draws upon a vast and diverse array of engineering talent, expertise and enthusiasm that spans multiple disciplines and, in some cases, a generation. Or two.

Kathryn Crowe is a twenty-something aerospace engineer who tweets from her smartphone and calls herself a “purveyor of the future.” Hugh Brady, on the other hand, began his career at Marshall during the days of punch cards and gargantuan room-sized IBM mainframes with an entire 16 kilobytes (!) of memory.

But if you think these two don’t have much common ground on which to build a strong working foundation, well, think again. Although the two aerospace engineers may be separated by a couple generations, they speak of each other with mutual admiration, respect and enthusiasm. And like any relationship built on a solid foundation, there’s room for fun, too.

Even though Brady’s career spans 50-plus years at NASA, he’s anything but jaded, to hear Crowe tell it. “Hugh still seems to keep that original sense of excitement. I figure if he thinks I’m doing okay, then I must be doing okay since he’s seen almost our entire history as an agency. It’s nice to have him to help keep me straight,” says Crowe, who recently received NASA’s Space Flight Awareness Trailblazer Award, which recognizes those in the early stages of their career who demonstrate creative, innovative thinking in support of human spaceflight. “And, he always tries to bring a sense of humor to everything he does.”

“I’ve enjoyed being mentored by Kathryn,” jokes the seventy-something Brady, who admits to failing retirement (twice, so far) because he loves the space program and can’t stay away. (Also, he said, because he doesn’t care for television. But mostly it’s because he loves space exploration and working with young, talented engineers.)

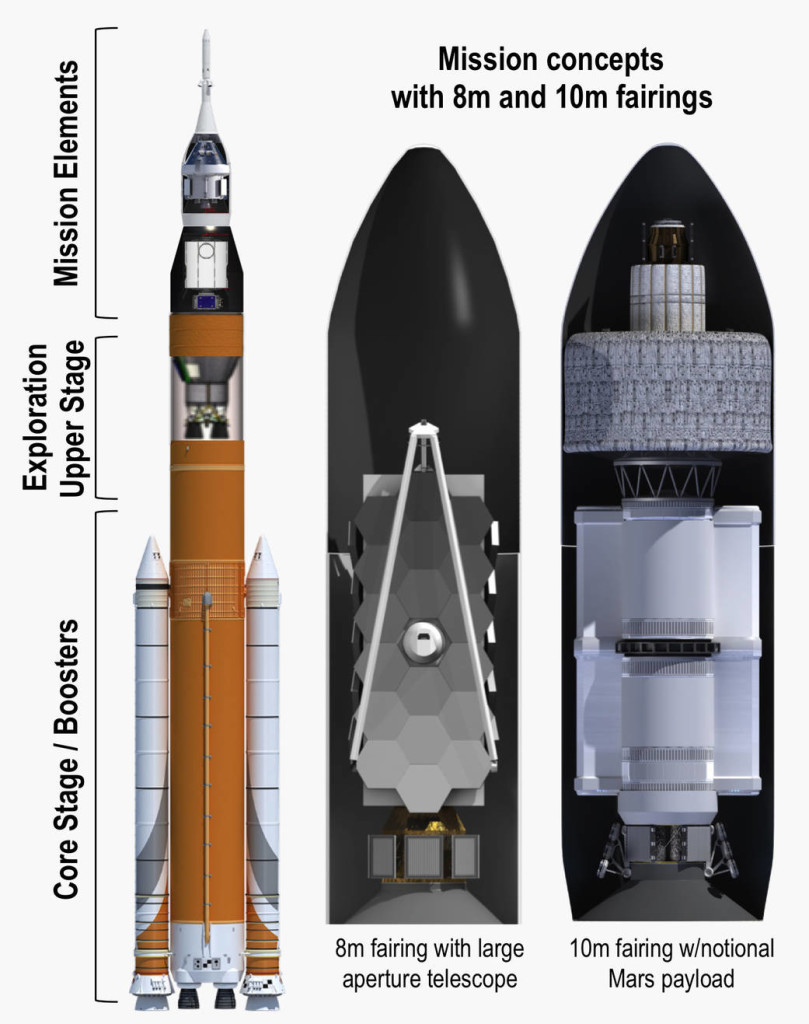

Crowe and Brady have worked together evaluating design options and deciding on solutions to make the second configuration of SLS as flexible and adaptable as possible. This upgraded configuration – known as Block 1B – adds a more-powerful upper stage and will stand taller than the Saturn V. It could fly as early as the second launch of SLS, which will be the first crewed mission to venture into lunar orbit since Apollo. Block 1B also presents the opportunity to fly a co-manifested payload, or additional large payload in addition to the Orion crew capsule.

For Crowe, a self-described “shuttle baby,” working on a future configuration of SLS means the chance to look at the big picture. “I like to have a global view on things. For this particular rocket, we’ve made it as flexible as we can. We can complete missions that we don’t even know the requirements for yet!”

For Brady, “Things have a tendency to repeat.” While technology and solutions continue to improve, some of the challenges of spaceflight will always remain the same. When it comes to wrestling with the challenges of a co-manifested payload, Brady draws on his experience, but focuses on solutions that are tailored for SLS. It’s bringing lessons from the past into the present in order to find the best solution for future missions. “It’s drawing on what we’ve learned from the past but not necessarily repeating the past. We want the best solution for this vehicle,” he emphasizes.

Crowe says the experience and knowledge Brady brought to the table made all the difference when studying options for the SLS vehicle. “Hugh would say, ‘I think we worked on this particular technical problem when we were initially flying.’ He could draw parallels so we didn’t reinvent the wheel,” Crowe says. Since then, Brady has become something of a mentor to Crowe and other younger team members.

“When you put that kind of technical information on the table it gives people better information – information that’s based on prior experience,” Brady says. “We may not pick the same solution, because technology changes over time, but we will have more and better information to use when making decisions.”

“I think that having that kind of precedent to build upon it really is a beautiful thing,” Crowe says.

For his part, Brady says he feels a “comfort” level in passing the United States’ launch vehicle capabilities on to the next generation of engineers and other supporting personnel. “One of the things I find very exciting is to look around and see the young talent around the center with their energy and enthusiasm. I feel good thinking about when I do hang it up – again – that they will carry on and even do more than we did,” he says.

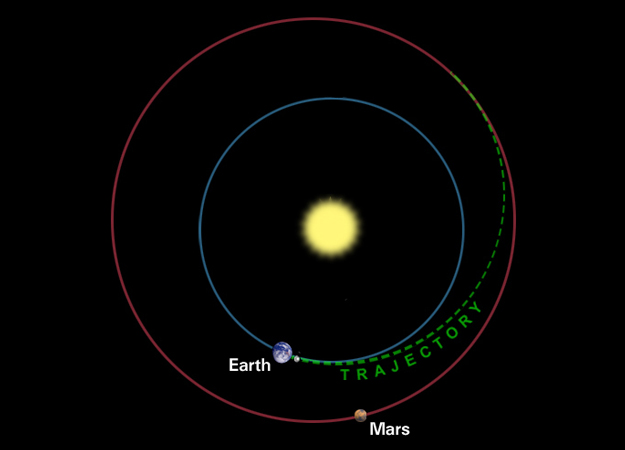

When you ask Crowe if humans will get to Mars, she says, “For sure I think within my lifetime I will see humans on Mars. I think more than ever right now is the right time to return to human spaceflight. We have the right skills and expertise. And when we successfully complete our mission and show that sort of hope to people again, that’s going to be equally as important as technological benefits.”

“That’s the objective,” Brady says. “I can’t wait until we fly again. It’s a tremendous feeling! It’s exhilarating! It’s time.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gXMhOe1pRKc[/embedyt]If you do not see the video above, please make sure the URL at the top of the page reads http, not https.

Join in the conversation: Visit our Facebook page to comment on the post about this blog. We’d love to hear your feedback!