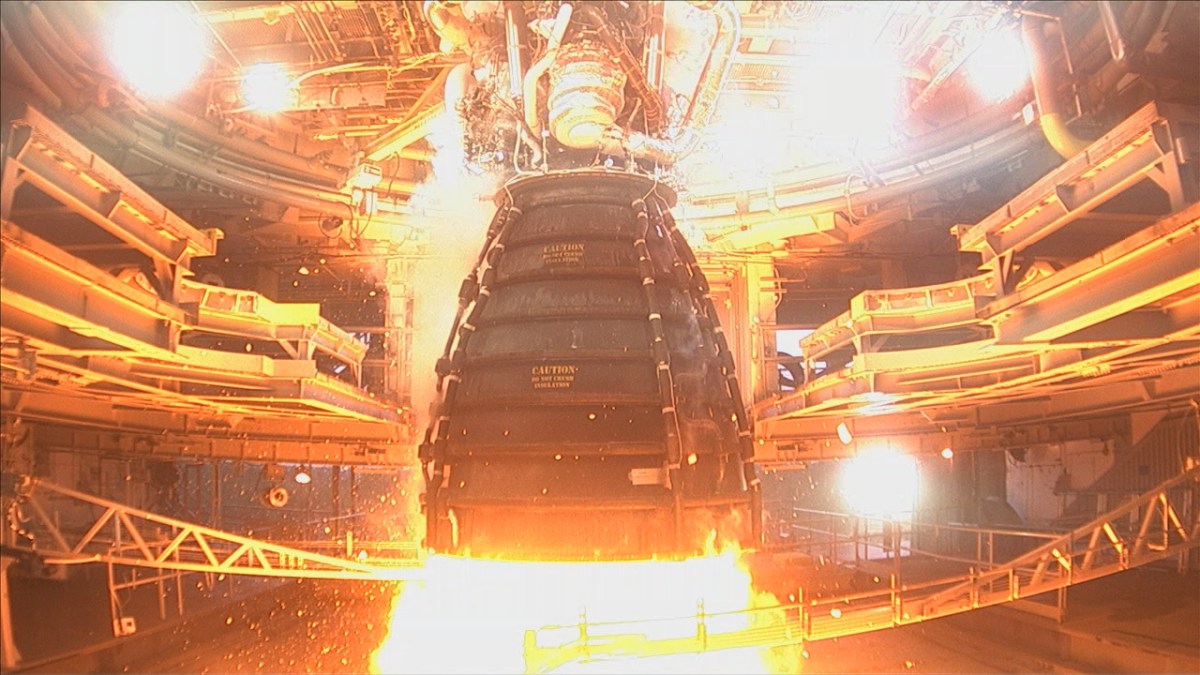

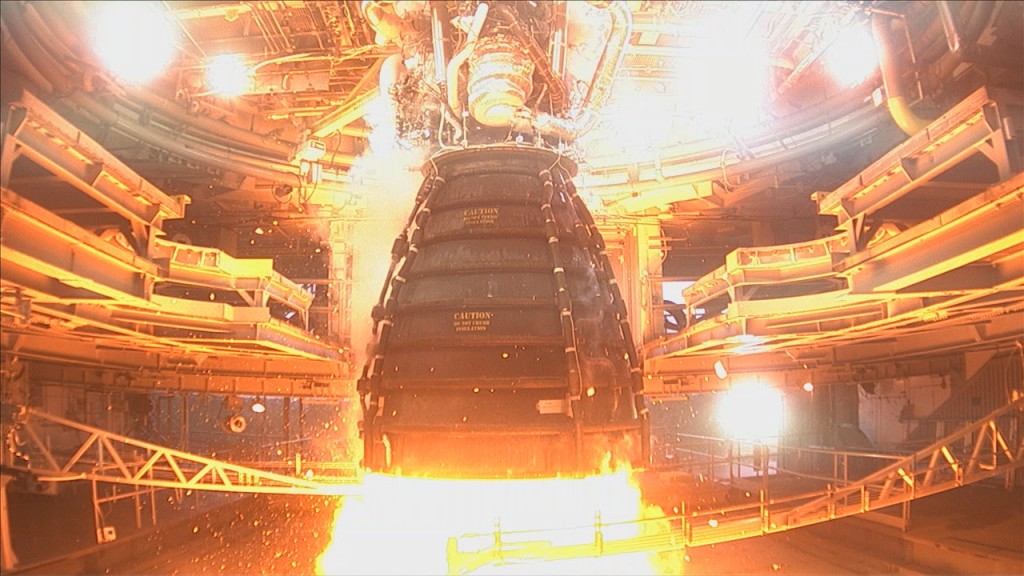

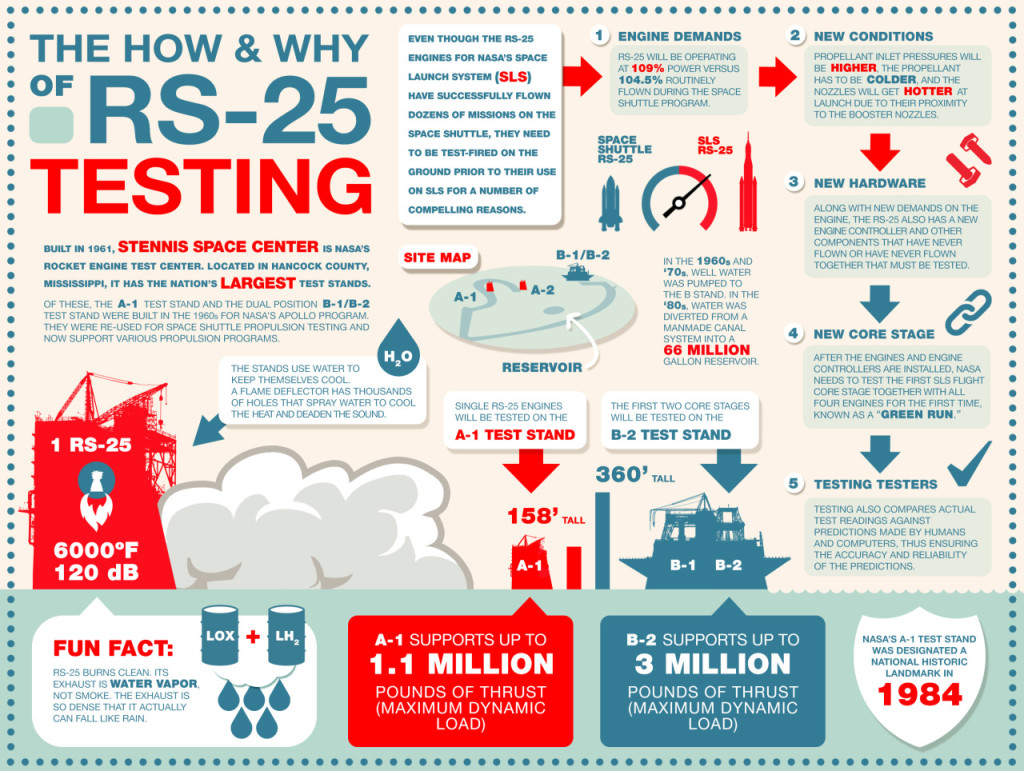

Earlier this month, another successful test firing of a Space Launch System (SLS) RS-25 engine was conducted at Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Engine testing is a vital part of making sure SLS is ready for its first flight. How do the engines handle the higher thrust level they’ll need to produce for an SLS launch? Is the new engine controller computer ready for the task of a dynamic SLS launch? What happens when if you increase the pressure of the propellant flowing into the engine? SLS will produce more thrust at launch than any rocket NASA’s ever flown, and the power and stresses involved put a lot of demands on the engines. Testing gives us confidence that the upgrades we’re making to the engines have prepared them to meet those demands.

If you read about the test – and you are following us on Twitter, right? – you probably heard that the engine being used in this test was the first “flight” engine, both in the sense that it is an engine that has flown before, and is an engine that is already scheduled for flight on SLS. You may not have known that within the SLS program, each of the RS-25 engines for our first four flights is a distinct individual, with its own designation and history. Here are five other things you may not have known about the engine NASA and RS-25 prime contractor Aerojet Rocketdyne tested this month, engine 2059.

1. Engine 2059 Is a “Hubble Hugger” – In 2009, the space shuttle made its final servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope, STS-125. Spaceflight fans excited by the mission called themselves “Hubble Huggers,” including STS-125 crew member John Grunsfeld, today the head of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Along with two other engines, 2059 powered space shuttle Atlantis into orbit for the successful Hubble servicing mission. In addition to its Hubble flight, engine 2059 also made four visits to the International Space Station, including the STS-130 mission that delivered the cupola from which station crew members can observe Earth below them.

2. The Last Shall Be First, and the Second-to-Last Shall Be Second-To-First – The first flight of SLS will include an engine that flew on STS-135, the final flight of the space shuttle, in 2011. So if the first flight of SLS includes an engine that flew on the last flight of shuttle, it only makes sense that on the second flight of SLS, there will be an engine that flew on the second-to-last flight of shuttle, right? Engine 2059 last flew on STS-134, the penultimate shuttle flight, in May 2011, and will next fly on SLS Exploration Mission-2.

3. Engine 2059 Is Reaching for New Heights – As an engine that flew on a Hubble servicing mission, engine 2059 has already been higher than the average flight of an RS-25. Hubble orbits Earth at an altitude of about 350 miles, more than 100 miles higher than the average orbit of the International Space Station. But on its next flight, 2059 will fly almost three times higher than that – the EM-2 core stage and engines will reach a peak altitude of almost 1,000 miles!

4. Sometimes the Engine Tests the Test Stand – The test of engine 2059 gave the SLS program valuable information about the engine, but it also provided unique information about the test stand. Because 2059 is a flown engine, we have data about its past testing performance. Prior to the first SLS RS-25 engine test series last year, the A1 test stand at Stennis had gone through modifications. Comparing the data from 2059’s previous testing with the test this month provides calibration data for the test stand.

5. You – Yes, You – Can Meet Awesome SLS Hardware Like Engine 2059 – In 2014, participants in a NASA Social at Stennis Space Center and Michoud Assembly Facility, outside of New Orleans, got to tour the engine facility at Stennis, and had the opportunity to have their picture made with one of the engines – none other than 2059. NASA Social participants have seen other SLS hardware, toured the booster fabrication facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and watched an RS-25 engine test at Stennis and a solid rocket booster test at Orbital ATK in Utah. Watch for your next opportunity to be part of a NASA Social here.

Watch the test here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njb9Z2jX2fA[/embedyt]

If you do not see the video above, please make sure the URL at the top of the page reads http, not https.

Next Time: We’ve Got Chemistry!

Join in the conversation: Visit our Facebook page to comment on the post about this blog. We’d love to hear your feedback!