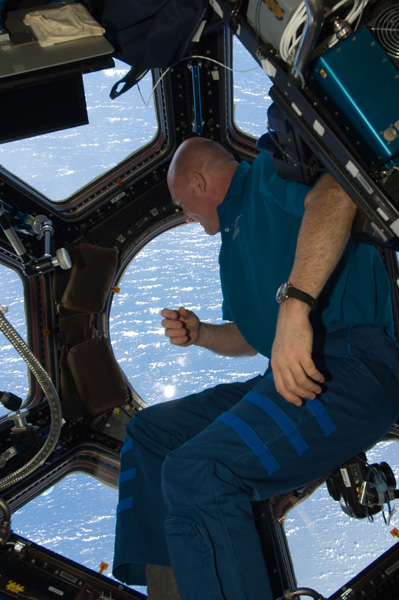

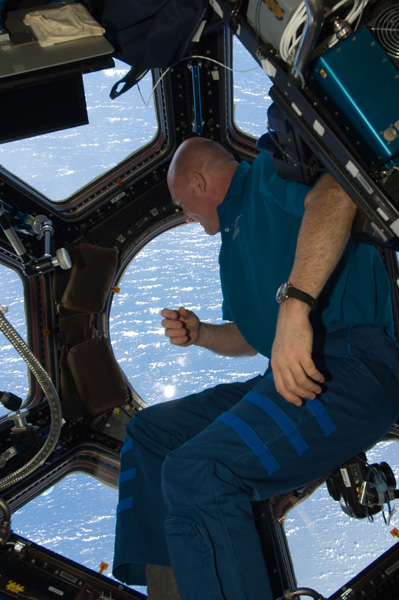

Looking through the cupola windows on Space Station, it’s only naturalto reflect upon who we are and where we fit into the world below. Likesomething out of Alice in Wonderland, this orbital lookingglass can be both a window through which to observe the jeweled sphereof Earth and a mirror that (sometimes, depending on your viewing angle)shows you a translucent reflection of yourself superimposed on theplanet.

Looking through the cupola windows on Space Station, it’s only naturalto reflect upon who we are and where we fit into the world below. Likesomething out of Alice in Wonderland, this orbital lookingglass can be both a window through which to observe the jeweled sphereof Earth and a mirror that (sometimes, depending on your viewing angle)shows you a translucent reflection of yourself superimposed on theplanet.

From orbit, the more you know about our planet, the more you can see.You see all the geological features described in textbooks. You seefault zones, moraines, basins, ranges, impact craters, dikes, sills,braided channels, the strike and dip of layered rocks, folding,meanders, oxbow lakes, slumps, slides, mud flows, deltas, alluvial fans,glaciers, karst topography, cirques, tectonic plates, rifts zones,cinder cones, crater lakes, fossil sea shores, lava flows, volcanicplumes, fissures, eruptions, dry lakes, inverted topography, lattericsoils, and many more.

You see clouds of every description and combination: nimbus, cumulus,stratus, nimbo-cumulus, nimbo-stratus, cirrus, thunderheads, andtyphoons, sometimes with clockwise rotation, sometimes withcounter-clockwise. You notice patterns: clouds over cold oceans lookdifferent than clouds over warm oceans. Sometimes the continents are allcloud-covered, so you have no recognizable landmass to help you gaugewhere you are. If you see a crisscross of jet contrails glistening inthe sun above the clouds, you know you are over the United States.

Lightning storms flash like gigantic fireflies looking for mates halfa continent away. You see patterns on the ocean surface, swirls andvortices on large scales, wave diffraction patterns around capes,solitary waves forming long lines out in the middle of nowhere, andrivers that look like they are spilling milk chocolate into turquoiseoceans.

You see light-scattering phenomena of all kinds—at sunrise, atsunset, across the terminator, 16 times a day. You see crepuscular rays,forward reddened lobes, off-axis blue lobes, and corona halos. Withbinoculars you can count six distinct layers in the atmosphere, with theouter one seemingly fading into fuzzy blackness.

The aurora is nothing short of occipital ecstasy. It is alwaysmoving, always changing, and like snowflakes, no two displays are thesame. The glowing red and green forms meander like celestial amoebascrawling across some great petri dish. One time our orbit took usthrough the center of an auroral display. It was as if we were in aglowing fog of red and green. Had we been shrunk down and inserted intothe tube of a neon sign? It looked like it was just on the other side ofthe windowpane. I wanted to reach out and touch, but of course Icouldn’t. Afterwards, I had to clean nose prints off of the window.

You catch an occasional meteor while looking down at Earth.You see stars and planets in oblique views, next to Earth’s limb. Andthey do not twinkle. Perchance you might spot a ragged shadow from atotal solar eclipse projected onto Earth. Amazing, it looks just like itdoes in the textbooks! You have a godlike view of the finer details ofshadowy projections onto spherical bodies. You see space junk orbitingnearby. Sometimes it flickers due to an irregularity, catching light asit rotates. An overboard water dump produces a virtual blizzard in thesurrounding vacuum. Like strangers passing in the night, you see othersatellites flash brilliantly for a few seconds, then fade into oblivion.

You catch an occasional meteor while looking down at Earth.You see stars and planets in oblique views, next to Earth’s limb. Andthey do not twinkle. Perchance you might spot a ragged shadow from atotal solar eclipse projected onto Earth. Amazing, it looks just like itdoes in the textbooks! You have a godlike view of the finer details ofshadowy projections onto spherical bodies. You see space junk orbitingnearby. Sometimes it flickers due to an irregularity, catching light asit rotates. An overboard water dump produces a virtual blizzard in thesurrounding vacuum. Like strangers passing in the night, you see othersatellites flash brilliantly for a few seconds, then fade into oblivion.

Jungles are the darkest land features you can observe in fullsunlight. They are so dark that you need to open your camera lens toobtain a proper exposure. If there are clouds partly shrouding yourview, you can be fooled into thinking you are over the ocean. Only whenyou notice rivers with braided channels and meandering loops ofchocolate brown do you realize that it is jungle and not water.Farmland, rich with vibrant crops, is different. Farmland is bright,much brighter than the jungles. Here nature is giving us a clue as tothe efficiency of light capture by plants.

The impact of humanity on Earth is humbling from orbit. Our greatestcities appear to the bare eye as minor gray smudges on the edges ofcontinents—they could be the fingerprints of Atlas, from the last timehe handled the globe. They are hardly distinguishable from volcanic ashflow or other geologic features. If you didn’t know it was a city, itwould be difficult to conclude it was the result of human design. Underthe scrutiny of the telephoto lens, things appear different. Like antsmoving crumbs of dirt, we are slowly changing our world. You realizethat Earth will do just fine, with or without us. We are wedded to thisplanet, for better or for worse, until mass extinction do us part.

Cities at nightare different from their drab daytime counterparts. They present a mostspectacular display that rivals a Broadway marquee. And cities aroundthe world are different. Some show blue-green, while others showyellow-orange. Some have rectangular grids, while others look like afractal-snapshot from Mandelbrot space.

Patterns in the countryside are different in Europe, North America,and South America. In space, you can see political boundaries that showup only at night. As if a beacon for humanity, Las Vegas is truly thebrightest spot on Earth. Cities at night may very well be the mostbeautiful unintentional consequence of human activity.

This looking glass incites your mind to ponder the abstract. Throughthe window, you explore the world. In the mirror, you reflect upon yourplace within it and the reasons we explore. Is it fundamentally aboutfinding new places to live and new resources to use? Or is it aboutexpanding our knowledge of the universe? Either way, exploration seemsfundamental to our survival as a species. After all, if the dinosaurshad explored space and colonized other planets, they would still bealive today.

Tierra del Fuego, the land of fire, was what Magellan named the tip of South America in 1520. He saw the fires set by local inhabitants who did not want the Portuguese explorer to set foot on their land.

Tierra del Fuego, the land of fire, was what Magellan named the tip of South America in 1520. He saw the fires set by local inhabitants who did not want the Portuguese explorer to set foot on their land.

Looking through the cupola windows on Space Station, it’s only naturalto reflect upon who we are and where we fit into the world below. Likesomething out of Alice in Wonderland, this orbital lookingglass can be both a window through which to observe the jeweled sphereof Earth and a mirror that (sometimes, depending on your viewing angle)shows you a translucent reflection of yourself superimposed on theplanet.

Looking through the cupola windows on Space Station, it’s only naturalto reflect upon who we are and where we fit into the world below. Likesomething out of Alice in Wonderland, this orbital lookingglass can be both a window through which to observe the jeweled sphereof Earth and a mirror that (sometimes, depending on your viewing angle)shows you a translucent reflection of yourself superimposed on theplanet. You catch an occasional meteor while looking down at Earth.You see stars and planets in oblique views, next to Earth’s limb. Andthey do not twinkle. Perchance you might spot a ragged shadow from atotal solar eclipse projected onto Earth. Amazing, it looks just like itdoes in the textbooks! You have a godlike view of the finer details ofshadowy projections onto spherical bodies. You see space junk orbitingnearby. Sometimes it flickers due to an irregularity, catching light asit rotates. An overboard water dump produces a virtual blizzard in thesurrounding vacuum. Like strangers passing in the night, you see othersatellites flash brilliantly for a few seconds, then fade into oblivion.

You catch an occasional meteor while looking down at Earth.You see stars and planets in oblique views, next to Earth’s limb. Andthey do not twinkle. Perchance you might spot a ragged shadow from atotal solar eclipse projected onto Earth. Amazing, it looks just like itdoes in the textbooks! You have a godlike view of the finer details ofshadowy projections onto spherical bodies. You see space junk orbitingnearby. Sometimes it flickers due to an irregularity, catching light asit rotates. An overboard water dump produces a virtual blizzard in thesurrounding vacuum. Like strangers passing in the night, you see othersatellites flash brilliantly for a few seconds, then fade into oblivion.