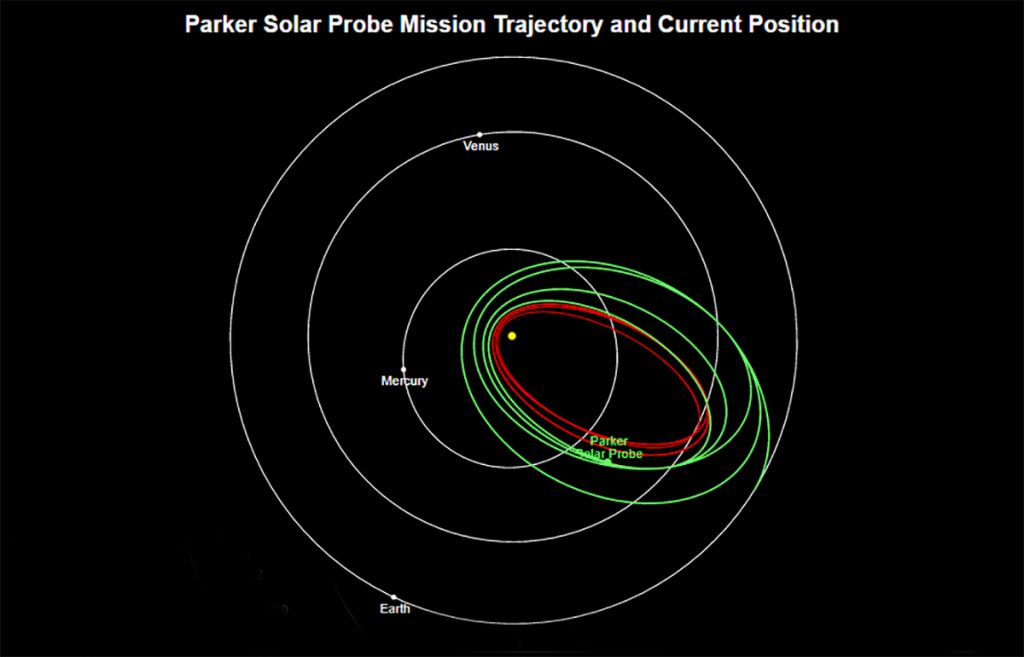

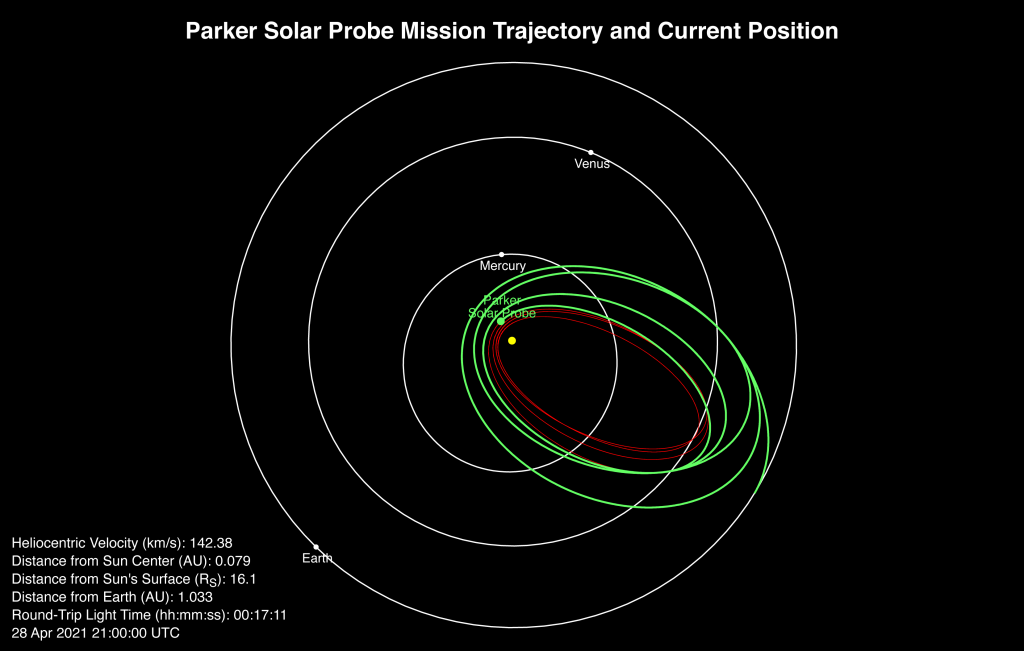

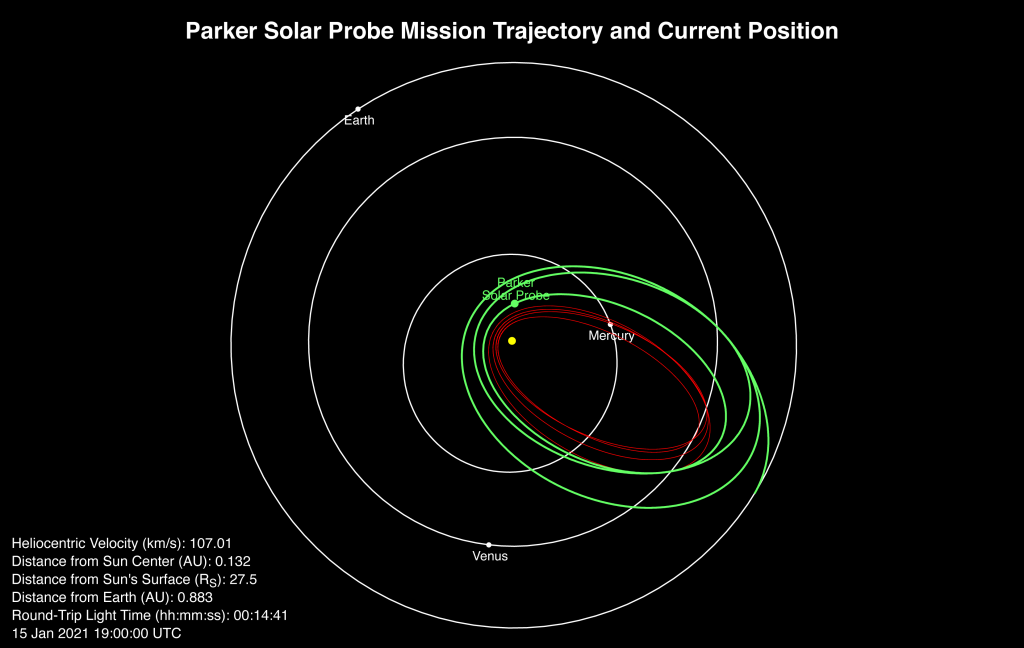

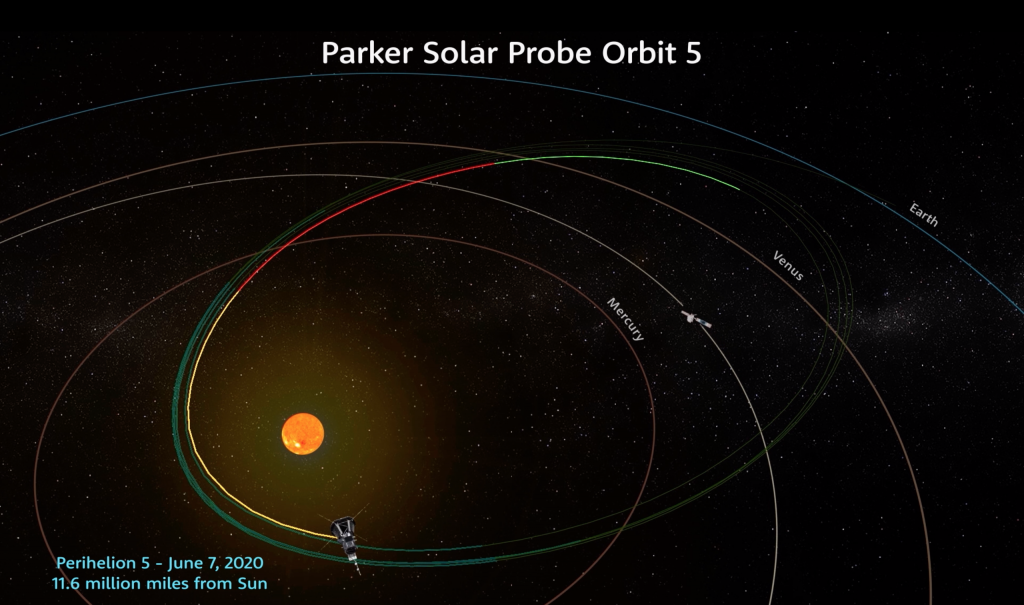

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is speeding busily through its ninth science-gathering solar encounter, heading toward a close approach of the Sun on Aug. 9 that will take it to within about 6.5 million miles (10.4 million kilometers, or 14.97 solar radii) of the solar surface.

That matches the record-distance of its last closest approach (called perihelion) on April 29; at the same time, the probe will also equal its record-setting flyby speed of 330,000 miles per hour (532,000 kilometers per hour). And, it’s only 2.6 million miles from the ultimate closest approach of 3.8 million miles from the Sun’s surface, which Parker Solar Probe will reach will reach in December 2024.

Designed, built and operated at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, Parker Solar Probe is operating normally heading into perihelion. Using its four onboard instrument suites, the spacecraft will continue collecting data on the solar environment and solar wind for this encounter through Aug. 15, with much of the data from the encounter expected back on Earth by Aug. 18.

“We are getting into the critical phase of the Parker mission and we’re focused on quite a few things during this encounter,” said Nour E. Raouafi, Parker Solar Probe project scientist from APL. “We expect the spacecraft to be flying through the acceleration zone of the perpetual flow of charged particles that make up the solar wind. Solar activity is also picking up, which is promising for studying larger-scale solar wind structures, like coronal mass ejections, and the energetic particles associated with them.

“But you never know what else you’ll find exploring this close to the Sun,” he added, “and that’s always exciting.”

Three years into its seven-year primary mission, Parker Solar Probe remains healthy while traversing a path that will take it directly through the Sun’s outer atmosphere, known as the corona. The Thermal Protection System shielding the spacecraft is already facing temperatures above 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit (650 degrees Celsius). At Parker Solar Probe’s closest approaches, the TPS must withstand temperatures of 2,500 F while keeping the spacecraft and instruments in its shadow operating at about 85 F.

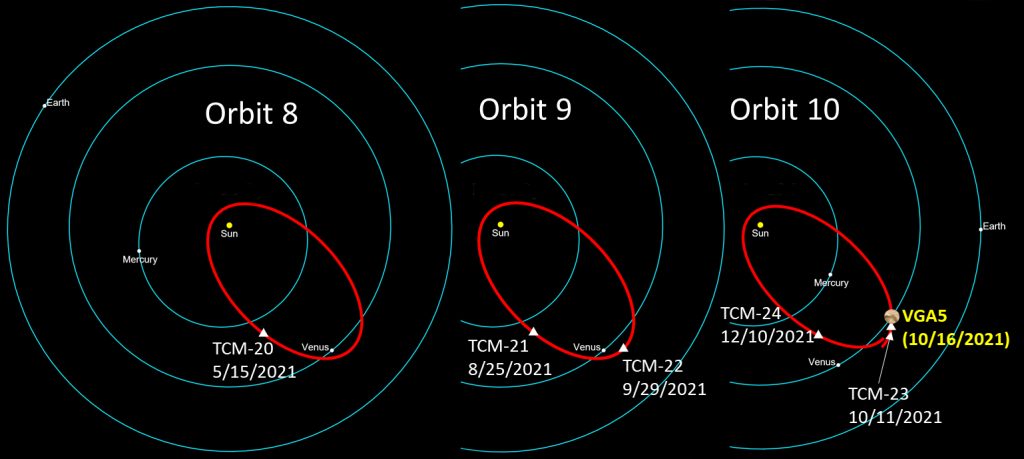

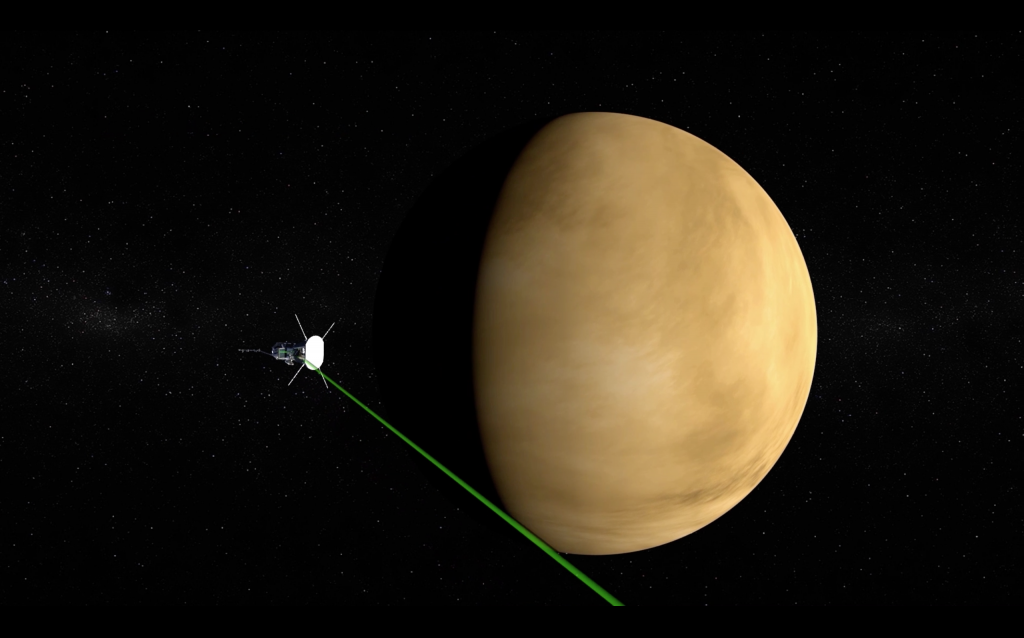

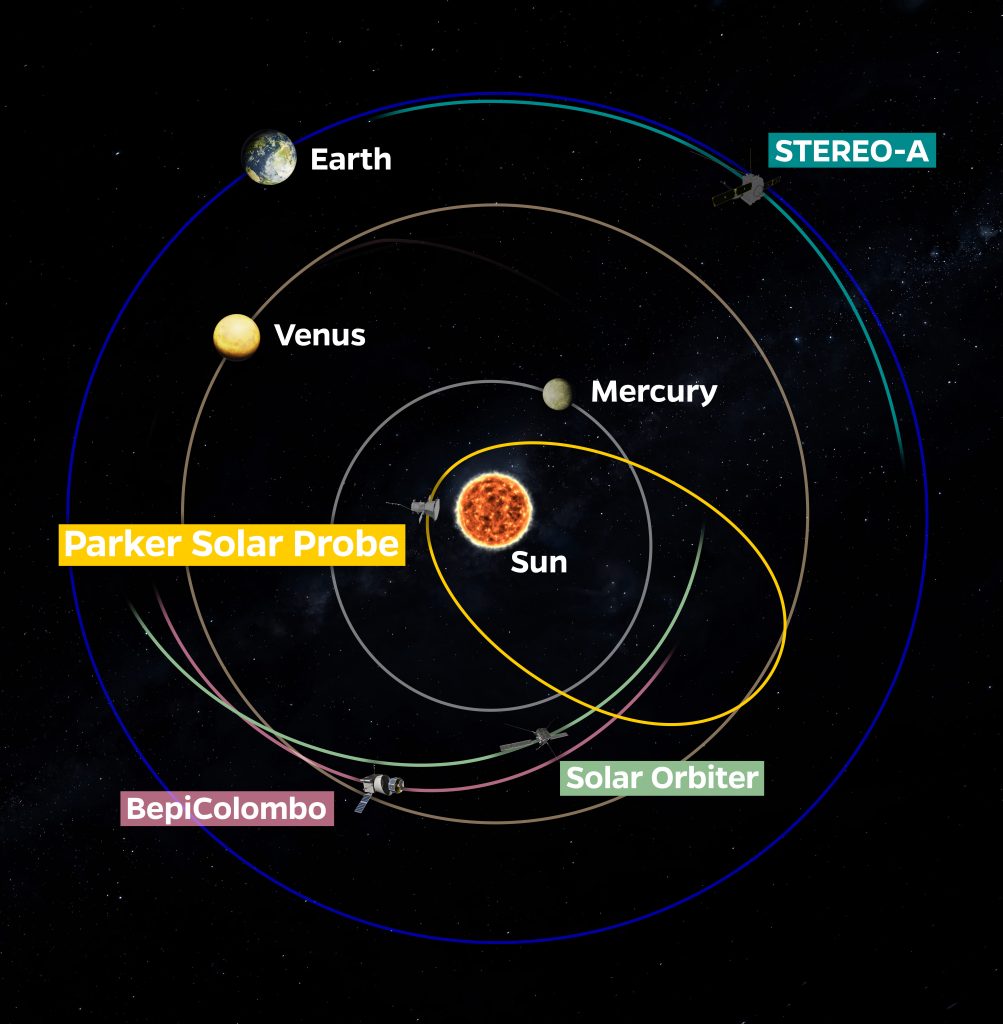

Preparations are underway for the mission’s fifth flyby of Venus, on Oct. 16, which will direct Parker Solar Probe even closer to the Sun for its 10th science orbit, which culminates with its fourth and final perihelion of the year on Nov. 21.

By Mike Buckley

Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab