Five hundred seconds is exactly eight minutes and twenty seconds. Nope, that’s not rocket science. But that was what I had to keep in mind as I watched the stopwatch application on my smart phone during the last J-2X test. Eight minutes and twenty seconds. That seems like a really long time when you’re counting every second.

Let me set the scene.

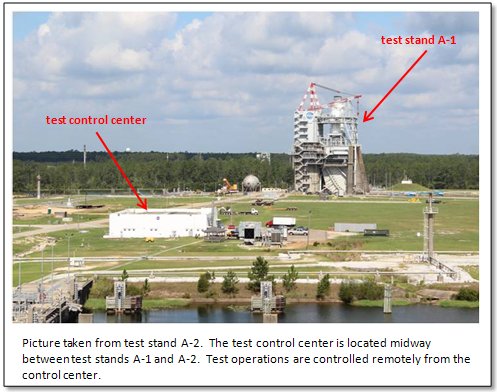

At the NASA Stennis Space center you have collected the directors from seven of the ten NASA field centers around the country. You have representatives from the NASA headquarters in Washington, DC. You have a live feed being picked up by NASA TV and broadcast into the living rooms of thousands or millions of dedicated NASA TV junkies. You have dignitaries in suits and technicians and test conductors in jeans and Hawaiian shirts (test-day tradition), reporters with notepads and cameras from every paper and television station in the greater New Orleans and southern Mississippi area, and, sitting in his ceremonial throne, the Grand High Exalted Mystic Ruler of the International Order of Friendly Sons of the Raccoons.

At the NASA Stennis Space center you have collected the directors from seven of the ten NASA field centers around the country. You have representatives from the NASA headquarters in Washington, DC. You have a live feed being picked up by NASA TV and broadcast into the living rooms of thousands or millions of dedicated NASA TV junkies. You have dignitaries in suits and technicians and test conductors in jeans and Hawaiian shirts (test-day tradition), reporters with notepads and cameras from every paper and television station in the greater New Orleans and southern Mississippi area, and, sitting in his ceremonial throne, the Grand High Exalted Mystic Ruler of the International Order of Friendly Sons of the Raccoons.

Well, okay, that last part about the Exalted Mystic Ruler is just fictional (bonus points to anyone who gets the 20th-century cultural allusion without Google help), but that’s the way that it felt. This was test A2J008, the seventh planned hot-fire test of the very first development engine and it was time to play show-and-tell.

Does everyone remember show-and-tell in elementary school? You bring in something that you think is neato or special and, by getting up in front of class and talking about it you reveal something about yourself and you accidentally practice public speaking and presentation. Once, when I was seven years old, I brought in my new baby brother, or, well, my mother did so at my behest. I wish that I could remember what I said about him. I imagine it was something like, “He’s short, cranky, and smells funny.” Today, at least he can say, he’s taller than me.

Does everyone remember show-and-tell in elementary school? You bring in something that you think is neato or special and, by getting up in front of class and talking about it you reveal something about yourself and you accidentally practice public speaking and presentation. Once, when I was seven years old, I brought in my new baby brother, or, well, my mother did so at my behest. I wish that I could remember what I said about him. I imagine it was something like, “He’s short, cranky, and smells funny.” Today, at least he can say, he’s taller than me.

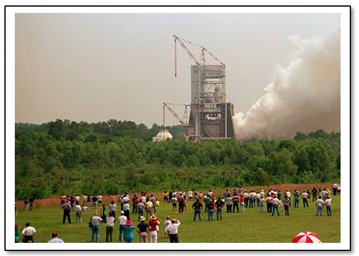

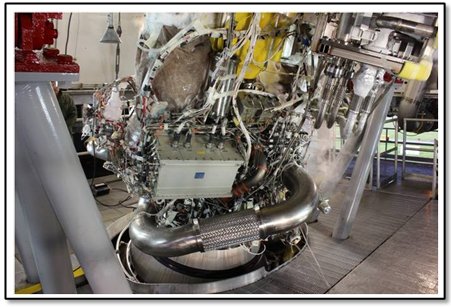

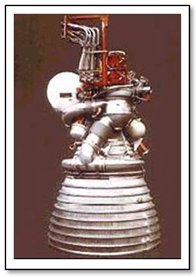

J-2X is our new baby brother — of a sort to carry forward the analogy — and we’re showing him off to the world. Through the first six hot fire tests of engine E10001, we accumulated a total of 225 seconds of test time. For test A2J008, on November 9th, our show-and-tell for the world, we scheduled a test lasting 500 seconds, which is the mission duration requirement for the engine. Here is what I saw during the test, while holding the stopwatch, standing out in the field in front of the test control center:

Can’t see anything? Okay, I’ll expand the picture in pieces starting on the left.

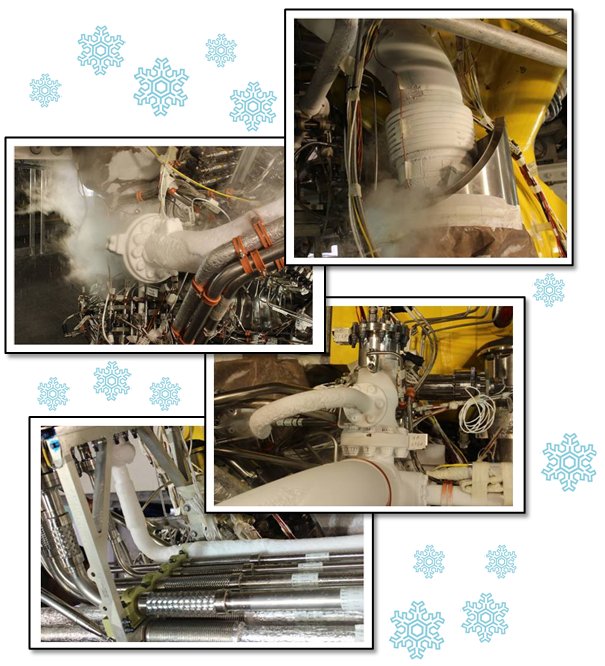

This is the hydrogen burn stack. All of the excess hydrogen coming from the facility or from the engine before, during, and after the test needs to be burned off. This is all bleed flows and waste flows that you cannot avoid when dealing with a cryogenic propellant. If you let hydrogen accumulate anywhere around the facility, then “BOOM” you’re eventually going to have an explosion. Talk to the guys who work out in the test areas and they’ll tell you plenty of tales of such things. What is amazing as you’re standing out in that field to watch the test is the radiation heat coming off that thing. It was a chilly day and yet you almost feel like you’re going to end up with a sun-tanned face. It feels like the sun while you’re on the beach except that as warm is it makes your front side, your back side is still chilly from the blustery November breeze. Kind of an odd sensation being both overheated and chilly at the same time.

This is the hydrogen burn stack. All of the excess hydrogen coming from the facility or from the engine before, during, and after the test needs to be burned off. This is all bleed flows and waste flows that you cannot avoid when dealing with a cryogenic propellant. If you let hydrogen accumulate anywhere around the facility, then “BOOM” you’re eventually going to have an explosion. Talk to the guys who work out in the test areas and they’ll tell you plenty of tales of such things. What is amazing as you’re standing out in that field to watch the test is the radiation heat coming off that thing. It was a chilly day and yet you almost feel like you’re going to end up with a sun-tanned face. It feels like the sun while you’re on the beach except that as warm is it makes your front side, your back side is still chilly from the blustery November breeze. Kind of an odd sensation being both overheated and chilly at the same time.

In the middle of the picture is a sign for anyone who was born without that instinctual reflex for self-preservation. While it would seem obvious to me to not walk in front of a roaring rocket engine throwing out a plume reaching hundreds of feet in the air, the fact that they have a sign like this suggests to me that for someone, somewhere, at some time, this was not so obvious. An unfortunate thought…

In the middle of the picture is a sign for anyone who was born without that instinctual reflex for self-preservation. While it would seem obvious to me to not walk in front of a roaring rocket engine throwing out a plume reaching hundreds of feet in the air, the fact that they have a sign like this suggests to me that for someone, somewhere, at some time, this was not so obvious. An unfortunate thought…

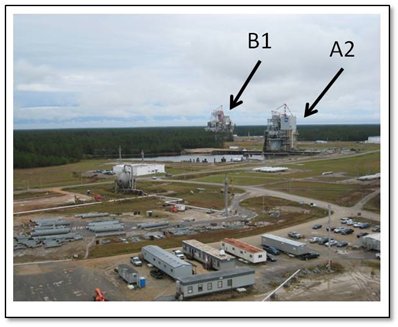

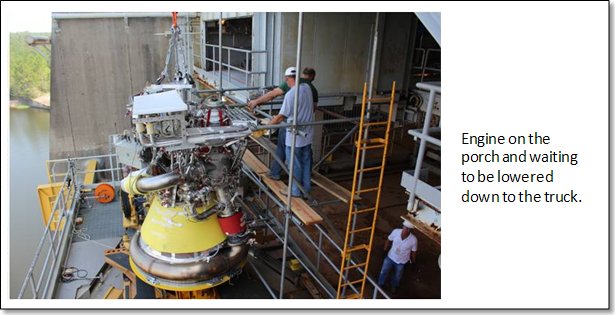

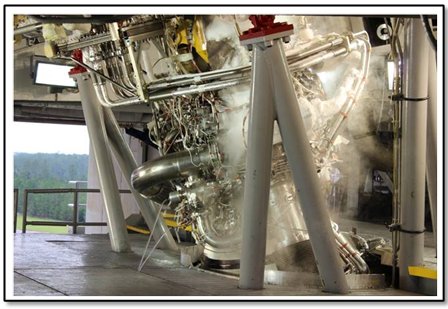

And, on the right-hand side of the picture, in the distance, is test stand A-2 with the engine firing. In the middle of the picture below, there is a tiny, very white spot in the middle of the test stand. That’s the flame coming directly out of the engine nozzle. In the bottom right corner of the picture below you can just see the edge of one of the liquid hydrogen barges. For both liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen, for extended duration tests, the propellant tanks on the test stand are not quite big enough to hold all of the necessary propellant. So, during the test you actually transfer propellants from these barges into the test stand tanks. So, the engine is draining the test stand tanks while you are simultaneously re-filling them from the barges. With all of this going on, you start to appreciate the coordination necessary to pull off one of these tests.

When you’re standing there being halfway cooked by the burn stack, several hundred feet away, the roar from the engine is nearly deafening. Many people wear hearing protection. Others of us are aging rock-n-roll fans. I honestly don’t think that anyone gets a complete sense of how powerful these machines are until they see, hear, and feel one of these tests. All of the performance numbers in the world simply do not have the same visceral impact as when the engine lights and the initial sound wave runs over, around, and through you and you watch the flame bucket fill with billowing, thick, white steam. Even twenty years after having seen my first test in person, I still cannot help but stand there like a bedazzled goof and say to myself, “Wow.”

Here, below, is a picture of the test from the other side of the stand. Why is this important (other than the sign on the fence clearly advertising what you’re looking at)? Because this is the side from which all of the non-NASA folks, some of the NASA dignitaries as well – including an astronaut representative – and the local press corps watched the test.

So as to not keep you in any more suspense, the test came off perfectly. The full, planned duration of 500 seconds was achieved thereby effectively tripling out test experience to date. The coverage on NASA TV was good. The bigwigs clapped and cheered with infectious excitement right along the rest of us. And the press corps wore out their thesauruses trying to capture just a slice of the actual experience. It was a complete success on all fronts.

Congratulations to the Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne J-2X development team, the NASA SSC test crew, and the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center project management team. While I had every bit of confidence that we’d be successful, with so many people watching our show-and-tell exercise, those 500 seconds — eight minutes and twenty seconds — ticking away on my stopwatch seemed like a whole lot longer. Whew! and Yahoo!

So I went on down to the local Ford dealership and announced to the salesman wearing a plaid jacket and striped tie that I wanted to buy a pickup truck.

So I went on down to the local Ford dealership and announced to the salesman wearing a plaid jacket and striped tie that I wanted to buy a pickup truck. I hung up the phone in an utter daze.

I hung up the phone in an utter daze.