By Dr. Stan Love

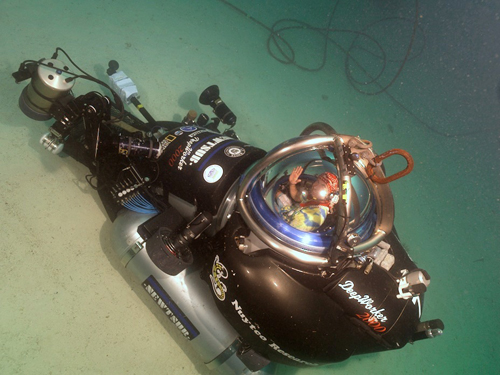

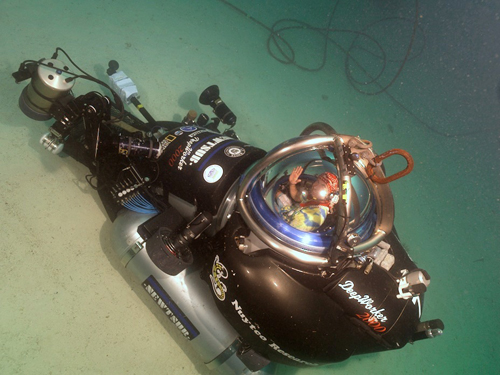

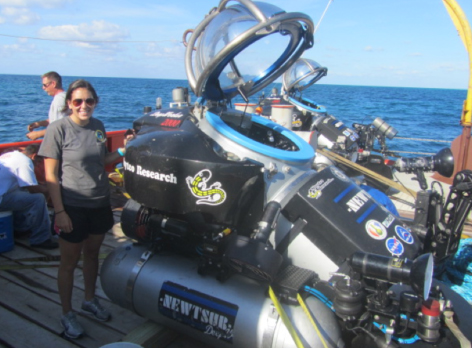

Image at right: Stan Love (in the sub) talks with Darlene Lim as he prepares for his nighttime DeepWorker flight.

Image at right: Stan Love (in the sub) talks with Darlene Lim as he prepares for his nighttime DeepWorker flight.

I last blogged inOctober 2011 during the 15th NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO)test. I had come to Florida to drive DeepWorker submersibles as part of NEEMO’sasteroid mission simulation, but the threat of a hurricane cut short our work.Although I didn’t get to drive the sub that year, there was an opportunity todo a short scuba dive at the Aquarius habitat, which provided more than enoughmaterial for a blog entry. Before that, I blogged about piloting the DeepWorkerin a deep, clear mountain lake in Canada for the Pavilion Lake Research Projectin July 2010.

This year I’m inFlorida again for NEEMO 16, working as a Capcom (Capsule Communicator) in the MobileMission Control Center and as a sub pilot. We’re about halfway through the Aquariuscrew’s twelve-day mission, which has been going smoothly and according to plan.Unfortunately there has been more uncertainty for the submersibles. Theyarrived here on time aboard the support ship Lana Rose, but technical problemsand high waves made it difficult to put them in the water for the marinescience dives they were scheduled to carry out during the first part of themission.

But late on WednesdayJune 13 the seas were calm, the subs were ready, and the pilot roster showed myname and that of marine biologist Steve Giddings. We rode out to the Lana Roseaboard Latency, a work boat from Kennedy Space Center that is serving as ourwater taxi between Aquarius headquarters in Key Largo and the habitat itself,which is several miles offshore. It was a lovely, calm late afternoon, withtowering clouds in the distance promising a spectacular sunset. The Lana Rosecrew welcomed us aboard. We shook hands with Big Jeff, Mike, and Little Jefffrom Nuytco Research. They take care of the subs, run all the pre-dive checklists,and monitor and navigate the subs during their underwater missions.

The sun set while wefinished preparations for the dive. Steve and I climbed into our subs, wentthrough our final checks, and got hoisted into the water. By then it wascompletely dark.

All my previousDeepWorker flights had been in daylight. Although the lighting was dim inVancouver harbor and at the bottom of Pavilion Lake, being in a sub in totaldarkness was a new experience for me. The small computer monitor and videocamera screens in the cockpit provided a little light, and I had twoflashlights on a cord around my neck, but the sub’s powerful external lightsshone out into empty water and showed nothing outside. It was a little likebeing in space.

The first step in aDeepWorker dive is to head to the bottom and hang out for a while. Followingthe instructions of the navigator aboard Lana Rose, I drove downward. Soon aflat, white, sandy bottom appeared in the circle of light from the sub. Isettled down onto it, about 100 feet below the surface. After a few tweaks tothe life support system, both the Topside team and I were ready to start themission.

Moving along theplanned route, the flat bottom suddenly ended in a steep incline: the slope ofConch Reef. You can’t imagine a greater contrast. Instead of a featurelessplain of white sand, here was a rough, jumbled wall of old reef rock encrustedwith thousands of sponges, sea whips, sea fans, and little coral colonies in apsychedelic kaleidoscope of red, orange, purple, mauve, and brown with anoccasional flash of fluorescent blue.

My job was to follow apre-planned route and to take detailed video imagery of whatever I encountered,focusing on coral colonies and the appropriately named barrel sponges. Therewere plenty of both, but it was the more mobile reef creatures that caught myeye the most. Early in the flight a small moray eel, white with black spots,stuck its head out of its cleft in the rock and gaped at me. Squadrons oftorpedo-like squid, a foot or so in length and with eyes that shone like acat’s, kept formation with the sub at the edge of its circle of illumination. Closeto the sub’s lights, a galaxy of small animals swarmed. There were thousands oftiny moving transparent rods, like little sections of pencil lead, and larvalsquid a centimeter or so in length that looked like they were made of glass.Frenetically corkscrewing pink worms wriggled past. Now and then a school ofshiny little fish would come up to eat the creatures attracted by the lights.

My job was to follow apre-planned route and to take detailed video imagery of whatever I encountered,focusing on coral colonies and the appropriately named barrel sponges. Therewere plenty of both, but it was the more mobile reef creatures that caught myeye the most. Early in the flight a small moray eel, white with black spots,stuck its head out of its cleft in the rock and gaped at me. Squadrons oftorpedo-like squid, a foot or so in length and with eyes that shone like acat’s, kept formation with the sub at the edge of its circle of illumination. Closeto the sub’s lights, a galaxy of small animals swarmed. There were thousands oftiny moving transparent rods, like little sections of pencil lead, and larvalsquid a centimeter or so in length that looked like they were made of glass.Frenetically corkscrewing pink worms wriggled past. Now and then a school ofshiny little fish would come up to eat the creatures attracted by the lights.

Meanwhile, the subneeded some attention beyond just manipulating the foot pedals to drive thethrusters. Topside asked for life-support checks now and then. My sub wastowing a fiber-optic umbilical, which provided a realtime video signal back tothe Lana Rose. At one point the cable got hung up on an obstruction and I hadto drive back along it to help free it. Now and then I saw the lights ofSteve’s sub passing by in the distance. He was not trailing a tether, butsometimes had to maneuver to avoid mine.

It was very hot in thecockpit. With an outside water temperature of 85 degrees F, and no way to makethe air in the sub cooler or drier, it was a bit like working in a steam room.A far cry from Pavilion Lake, whose 38-degree water meant that DeepWorkerpilots had to fly in pile jackets, hats, and wool socks! Now I was wearing aT-shirt and swim trunks and was still too warm. But the view outside the subwas so incredible that I rarely noticed the heat.

At one point, Topside suggestedthat I settle on a patch of sand, turn off my lights, and look forbioluminescence. I tried that, aiming my video camera up into the water columnto see if any creatures out there were making their own light. With the lightsoff, it was profoundly dark outside. I looked hard for flashes of blue orgreen, but didn’t see any. I turned the lights back on and moved toward thenext waypoint.

Ever since I waslittle, I’ve thought that cephalopods (squids, octopuses, and their relatives)were cool. I encountered plenty of them on this mission, besides the onesalready mentioned. A cuttlefish, with a plump brown-striped body and tentaclesheld rigidly curled in front of it, cruised past the sub’s transparent dome.Abruptly, its stripes grew wider and darker, demonstrating the amazingcolor-changing ability that these animals possess. Then the cuttlefish zippedaway. Later in the mission, out on another sandy flat, my eye caught motion ina large conch shell resting in the sand. I drove the sub over for a closer lookat what I thought would turn out to be another hermit crab, several of which Ihad already seen trundling across the sea bed with their snail-shell houses ontheir backs. But the animal that cautiously peeked back out of this shell wasno hermit crab. It was soft, and mottled brown, with a pulsing mantle and asiphon. It was an octopus! I hadn’t seen one in the wild since I was a kid.What a treat! I recorded some video for the biologists, then turned the subaway only to see a large spiny lobster scuttle past. It seemed to know that itwas in a bad place, out on the sand and far from the protective cover of thereef, and was making all speed for a better place to hide.

All too soon Steve andI reached the final waypoints of our flight plans and it was time to return tothe ship. We had been in the water for almost four hours and it was well pastmidnight. As we prepared to surface, Steve brought his sub close to mine, thentook video of me leaving the sea floor. I lifted off slowly, the sub rotatingslightly to bring its lights in line with the ship above and trailing a plumeof disturbed sediment behind it. It looked very much like a slow-motion versionof an Apollo lunar ascent module lifting off the Moon forty years ago.Meanwhile, aboard ship, another video camera recorded the brilliantly lightedsub approaching the surface in a circle of bright blue water.

Once back on deck, theNuytco crew helped Steve and me secure the sub cockpits and climb out. Latencyshowed up a few minutes later to take us back to shore and sleep after anincredible night dive.

I have two more dayshere at NEEMO 16. With luck, I’ll fly another sub mission. This one will have avery different focus. Instead of taking images and making observations for marinebiology, I’ll be working with the aquanaut crew on a very complex real-timeunderwater simulation of a human exploration mission to a near-Earth asteroid.But that will be a topic for a future blog.

Learn more about NEEMO at www.nasa.gov/neemo

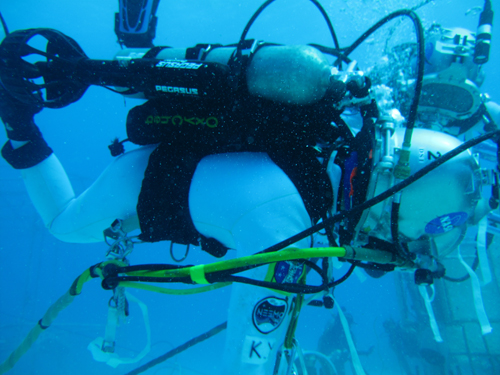

Image at right: Squyres performs an EVA while mounted to a DeepWorker sub piloted by NEEMO Mission Manager Bill Todd.

Image at right: Squyres performs an EVA while mounted to a DeepWorker sub piloted by NEEMO Mission Manager Bill Todd.

Image at right: Stan Love (in the sub) talks with Darlene Lim as he prepares for his nighttime DeepWorker flight.

Image at right: Stan Love (in the sub) talks with Darlene Lim as he prepares for his nighttime DeepWorker flight. My job was to follow apre-planned route and to take detailed video imagery of whatever I encountered,focusing on coral colonies and the appropriately named barrel sponges. Therewere plenty of both, but it was the more mobile reef creatures that caught myeye the most. Early in the flight a small moray eel, white with black spots,stuck its head out of its cleft in the rock and gaped at me. Squadrons oftorpedo-like squid, a foot or so in length and with eyes that shone like acat’s, kept formation with the sub at the edge of its circle of illumination. Closeto the sub’s lights, a galaxy of small animals swarmed. There were thousands oftiny moving transparent rods, like little sections of pencil lead, and larvalsquid a centimeter or so in length that looked like they were made of glass.Frenetically corkscrewing pink worms wriggled past. Now and then a school ofshiny little fish would come up to eat the creatures attracted by the lights.

My job was to follow apre-planned route and to take detailed video imagery of whatever I encountered,focusing on coral colonies and the appropriately named barrel sponges. Therewere plenty of both, but it was the more mobile reef creatures that caught myeye the most. Early in the flight a small moray eel, white with black spots,stuck its head out of its cleft in the rock and gaped at me. Squadrons oftorpedo-like squid, a foot or so in length and with eyes that shone like acat’s, kept formation with the sub at the edge of its circle of illumination. Closeto the sub’s lights, a galaxy of small animals swarmed. There were thousands oftiny moving transparent rods, like little sections of pencil lead, and larvalsquid a centimeter or so in length that looked like they were made of glass.Frenetically corkscrewing pink worms wriggled past. Now and then a school ofshiny little fish would come up to eat the creatures attracted by the lights. Image at right: The topside crew discuss communications delay scenarios in the mobile mission control center.

Image at right: The topside crew discuss communications delay scenarios in the mobile mission control center.

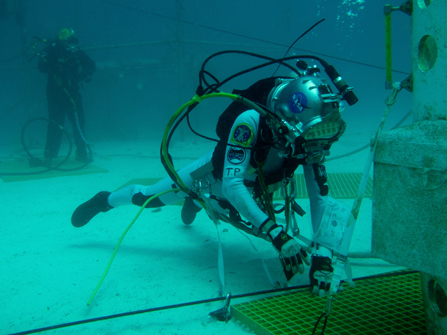

Image at Right: Tim Peake prepares to anchor so he has a stable platform from which to gather samples.

Image at Right: Tim Peake prepares to anchor so he has a stable platform from which to gather samples.