To understand the role that external tanks play and why this trip begins in eastern New Orleans on the Intracoastal Waterway, you have to start where they are built, NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility.

The original tract of land where Michoud Assembly facility was built was part of a 34,500-acre French Royal land grant to local merchant Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent in 1763. By the early 1800s, the property was owned by architect and engineer Bartholomey Lafon, whose maps of the waters surrounding the tract were used in defeating the British in the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. Near Chalmette, LA, a few miles from Michoud, the mischievous British army advanced in the open against a mixed force of U.S. Army regulars, American Indians, New Orleans militia and local buccaneers hunkered down behind hastily built trenches and barricades. Massed rifle and musket fire turned the British formation into shambles before the British withdrew, losing 2,000 casualties, their commanding general, Edward Pakenham, and the two other most senior officers.

Later, the land was acquired by French transplant Antoine Michoud, who moved to the city in 1827. Michoud operated a sugar cane plantation and refinery on the site until his death in 1863. His heirs continued operating the refinery and kept the original St. Maxent estate intact into the 20th century. Two brick smokestacks from the original refinery still stand on the Michoud facility grounds.

In 1940, the U.S. government purchased the land as a site for war-related construction. Three years later, the world’s largest production building at the time, covering 43 acres under one roof, was completed. The plant was used during World War II to build cargo planes and other aircraft, and again during the Korean War to produce tank engines.

The Michoud facility was acquired by NASA in 1961, after its availability was brought to the space agency’s attention by Wernher von Braun, known as the father of the Saturn family of rockets, who was named the first director of Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., in 1960.

Managed by the Marshall Center, Michoud includes one of the world’s largest manufacturing plants, with 43 acres under one roof, and a port permitting transportation of large space systems and hardware.

Building External Tanks

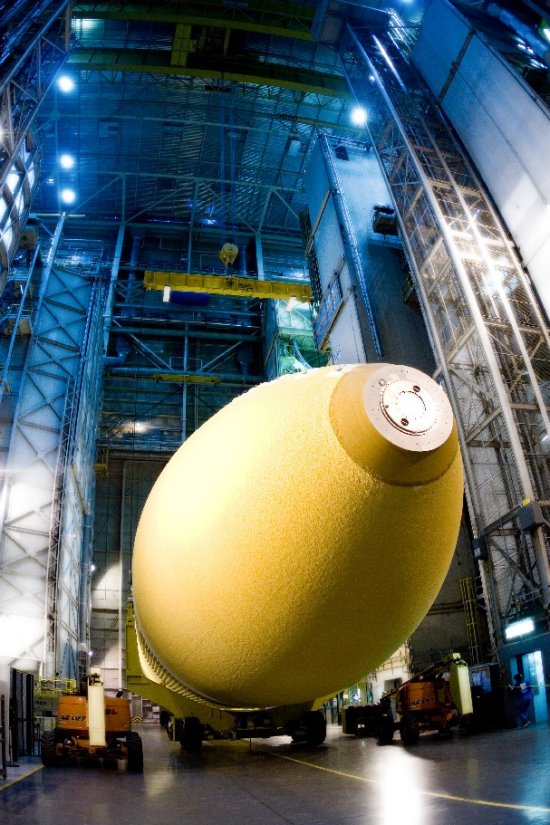

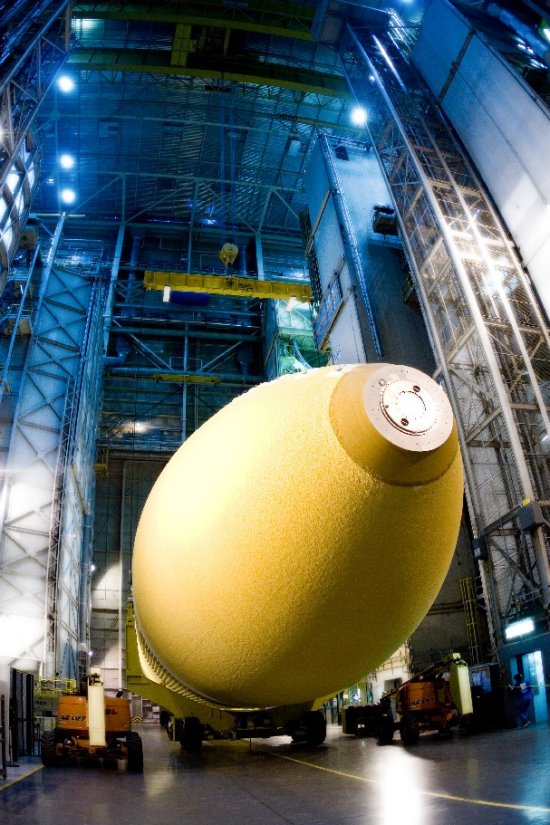

External tanks are assembled at Michoud from hardware delivered by hundreds of sub-contractors and vendors. Once the components are positioned at Michoud, a small army of aerospace workers begin the almost three year process to fully assemble, weld, test and inspect a new external tank.

Flickr Gallery: External Tank Assembly

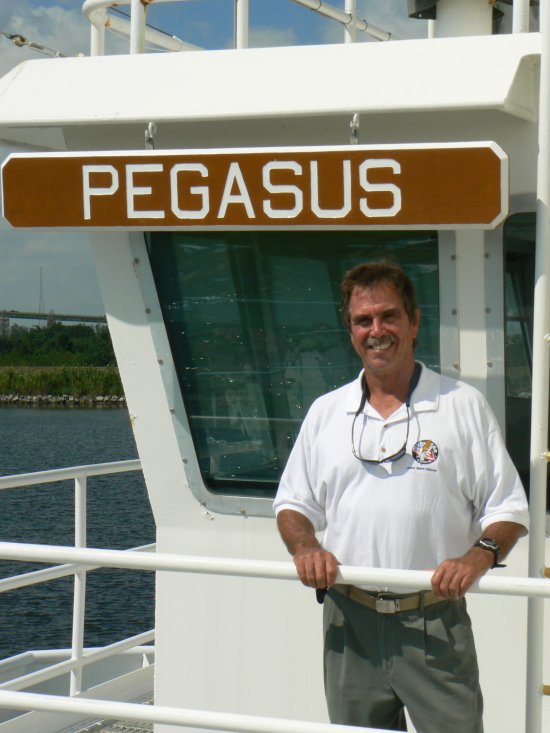

Today there are four external tanks in the assembly line at Michoud, ET-135 thru ET-138. All of these tanks will board Pegasus in late 2009 or early 2010 and make the 900-mile trip from Michoud to Kennedy Space Center to play their vital role in supplying the Space Shuttle Main Engines with 145,000 gallons of liquid oxygen and 390,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen during the first eight-and-a-half-minutes of launch. One additional tank resides at Michoud, but it may never fly. ET-122 was present at Michoud when Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana in 2005 and was damaged. In fact ET-122 is now being repaired to serve as the very last tank of the Space Shuttle Program, the Launch on Need tank for the last scheduled space shuttle mission, STS-133, in the fall of 2010. If all goes well with that mission ET-122 should never fly.

Flickr Gallery: External Tank Assembly

After the loss of space shuttle Columbia in February 2003, NASA went to work to redesign and improve many components of the structures of the external tanks and the application processes of the all important foam, also known as the Thermal Protection System or TPS. Major improvements have been made to the tank’s forward bipod fitting area, the liquid hydrogen tank Ice Frost Ramps, the intertank flange area, and the liquid oxygen feedline brackets and bellows. The tank’s protuberance air load ramps — known as PAL ramps — were also removed.

By the summer of 2008 external tank foam application and new designs had reduced the amount of foam being released during launch to very small, if not tiny amounts of foam. The successful reduction in foam debris came as a result of a non-stop process of continuous improvement to make shuttle launches as safe as possible, recognizing that external tanks will still release very small amounts of foam. Even with a few hiccups, the external tanks flying today are the safest and best tanks ever flown in the history of the shuttle program.

The newest tanks, including ET-134, have been welded using a new welding technology called Friction Stir Welding, a technique better than conventional fusion welding. Friction stir welding is different in that the materials are not melted. A rotating tool pin uses friction and pressure to plasticize the metal and join the two parts together. As a result, weld joints are more efficient, yielding 80 percent of the base strength. Fusion welding averages 40 to 50 percent of the base material’s strength. In fact ET-134 is the first external tank to have most of its liquid hydrogen tank welding performed by friction stir welding.

Flickr Gallery: External Tank Assembly, Friction Stir Welding

Flickr Gallery: External Tank Assembly, Friction Stir Welding

Here’s the status of the remaining external tanks:

ET-133/STS-129 is poised to launch from KSC in November

ET-134/STS-130 is en route to KSC with Pegasus

ET-135/STS-131 is in assembly at MAF

ET-136/STS-132 is in assembly at MAF

ET-137/STS-134 is in assembly at MAF

ET-138/STS-133 is in assembly at MAF

With the upcoming completion of the Space Shuttle Program in 2010 the end of the assembly line at Michoud is coming to an end as well. The number of workers at Michoud building external tanks is declining steadily and eventually there will be no work on external tanks. Work will eventually shift to other NASA projects.

As NASA enters a new era in space travel, the Michoud Assembly Facility is poised to continue its legacy, providing vital support to NASA’s mission to return humans to space and perhaps the moon, Mars and perhaps to extend a human presence into the solar system.

Katrina

To fully understand Michoud today you have to understand what the facility and what its employees experienced in late August 2005; Hurricane Katrina.

My first trip to Michoud was in the aftermath of Katrina. I traveled by air to Gulfport, Miss. and then overland to Stennis Research Center located some 40 miles to the east of Michoud. I then traveled with Marshall Security from Stennis to Michoud overland via Interstate 10 and Highway 11 thru Slidell, La. What I saw in Slidell was truly a shock. The portion of Slidell nearest the coast on Lake Pontchartrain had been badly flooded and was abandoned rubble; giant toothpicks lay everywhere. The most dangerous part of Katrina had passed to the east of Slidell and smashed the small Mississippi coastal towns like Waveland, Pass Christian and Gulfport, but Slidell received much of the wrath of Katrina as well. Entire neighborhoods of Slidell were nothing more than stacks of debris twenty feet high; people’s homes, schools, and businesses; people’s hopes and dreams. It was a wrenching sight.

What I didn’t know then was that many Slidell area residents and other residents of mauled East New Orleans represented much of the Lockheed Martin workforce at Michoud; the workforce that builds external tanks; the backbone and gas tank of Shuttle Transportation System.

Our little convoy passed over Lake Pontchartrain on Highway 11, which unlike I-10 was still standing, crossed under the Interstate 10 overpass and entered Irish Bayou. There were few structures standing in Irish Bayou. One man was living alone in a house built on stilts and our security detachment stopped to check up on him. His home had a roof and only three walls and he was very tired and haggard. His job, a cook in a restaurant in Slidell, no longer existed. Over the next few days on subsequent daily trips our security detachment dropped off small amounts of food and water for the lone survivor and although money wasn’t worth much because nothing was open, I gave him my travel money. In the early days after Katrina Lockheed Martin employees of the rideout team and a Marshall Security detachment were the first group to clear a route of debris along this portion of Highway 11 thru Irish Bayou, permitting vehicle traffic to enter East New Orleans and travel to Michoud.

We continued into eastern New Orleans and worked our way to Michoud proper. I had only a very vague idea of how Michoud had fared during Katrina. Michoud was intact, standing with some damage, but I had no real idea how the external tank production line had fared. After meeting with the Michoud/NASA Chief Operating Officer Patrick Scheuerman, I headed across to see the external tank manufacturing floor in Building 103 and assess the area for a stand up location for an upcoming television interview with Miles O’Brien of CNN, pre-arranged by my colleague and friend Dave Drachlis. Miles O’Brien had been covering the New Orleans story since early post Katrina and he had shown interest interviewing members of the Michoud Hurricane Rideout Team, all Lockheed Martin employees, who made up the vast majority of Michoud employees building NASA’s external tanks.

U.S. Marines, Colorado and Washington state National Guard soldiers and Canadian and American search and rescue personnel dotted the landscape of Michoud. Helicopters of all types came and went regularly, particularly the helicopters of the U.S. Coast Guard. Everyone knows about their incredible service to the people of New Orleans.

Then I received the second shock of the day. I entered the all important manufacturing floor of Building 103. I could see perhaps two or three small puddles of water and some disturbed roofing, but everything else including several external tanks near completion was untouched. In fact it was so clean and orderly it nearly took your breath away. I crossed to the west side of Building 103 and picked the spot. Miles O’Brien would be brought here to shoot the interview, looking back to the east along the aligned sight of transporters, liquid oxygen tanks, liquid hydrogen tanks, intertanks and welding tools; all in pristine condition. I let out a sigh; Michoud was an island in a sea of disaster and the shuttle program had dodged a bullet, but not the Lockheed Martin employees of Michoud. Words like catastrophic, devastated and heart-rending are understatements at best to describe the condition of the greater New Orleans area, the city to which Michoud employees were now returning.

The International Space Station photographed Katrina’s damage from 230 miles

above. While Michoud (right) is largely dry, the adjacent neighborhoods are

extensively flooded. (NASA)

The next day went like clockwork. Miles O’Brien checked in by cell phone and eventually flew by commercial helicopter into Michoud for the interview. He readily accepted the shoot location and interviewed three members of the rideout team, Lockheed Martin technicians who had operated the vital pump house pushing water out of Michoud as fast as it entered. Michoud could have flooded without the pump house and its team of technicians who braved wind and rain and drove in little visibility to keep the pumps working.

One day later, while eating lunch next to a group of U.S. Marines in the recently restarted cafeteria, CNN started running the Miles O’Brien interview with the Michoud members of the rideout team. The cafeteria television was tuned to CNN and quickly caught everyone’s attention as Miles O’Brien described the heroic deeds of those who had risked their lives for the nation’s space program. As a body, the Marines stood on their feet and clapped and cheered for the space workers present in the cafeteria, including many members from the rideout team. It was quite a moment. These were Marines that a few months earlier had just returned from combat operations in Faluja, Iraq. It was a fine tribute from one great body of Americans to another.

John Schwartz of the New York Times also braved the hot weather and minimal amenities and interviewed the rideout team at Michoud. He was great to work with. He wrote a good story.

By way of wrapping up the week at Michoud, Marshall Television deployed a production team consisting of Bob Moder, James Bilbrey and Mick Speer to document the recovery work underway at Michoud and shoot interviews for NASA Television. This done we packed up and headed back to Huntsville, Ala. NASA television began broadcasting this video of Michoud the next day.

By late October 2005 sufficient workers of Michoud’s Lockheed Martin team had returned to work to restart the external tank assembly line. It should not be forgotten that many of these workers in the months ahead worked one or sometimes two shifts at the assembly line and then returned to their homes in the evening to strip their homes of moldy sheet rock, ruined furniture and appliances, ruined carpet and to shovel mounds of mud and other debris out of immediate sight. It was a non-stop work in progress for a highly dedicated group of aerospace workers.

I returned to New Orleans in June 2006 with my volunteer church group to help prepare houses for refurbishment. We worked for several days in Gentilly and East New Orleans pulling down moldy sheet rock, attic insulation and removing furniture and battered appliances; saving the home owners something like $8,000 each. At 95 degrees it was hot work. Insulation stuck like little pins in every corner, nook and cranny, as we sweated and heaved gunk and junk. Upon leaving New Orleans on the last day our group decided to pass through the Ninth Ward. Although the streets were clear of debris, almost every structure was badly mauled or unrecognizable; homes, businesses and churches had imploded from force of tons of water sloshing back and forth. It was the saddest sight I’ve ever seen, and I couldn’t help but wonder what happened to all these people.