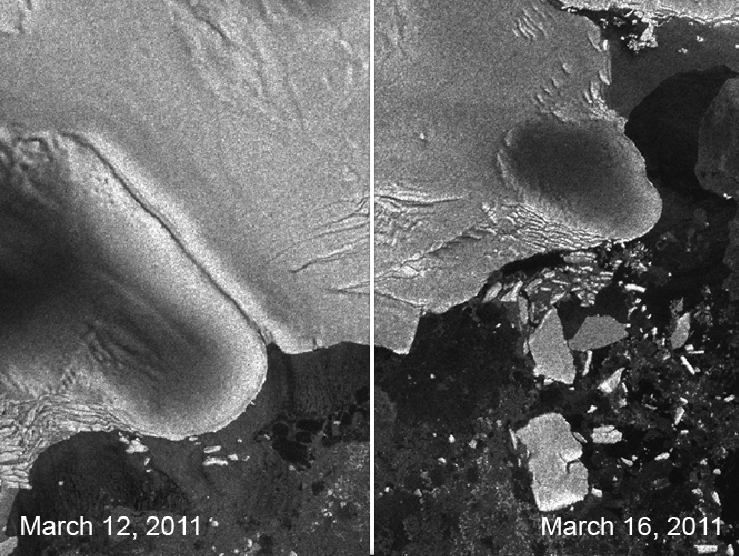

Today’s big Earth science news was that the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in March was strong enough to send waves that snapped a Manhattan-sized chunk of ice off the Sulzberger Ice Shelf some 8,100 miles away.

That’s true, but as pointed out at the end of this piece there’s more to this story than just the strength of the earthquake. Though it’s not making it into the headlines, the condition of the ice in the region was also key. Specifically, the lack of nearby sea ice, coastal ice (also called fast or landfast ice) and pack ice made the portion of the Sulzberger Ice Shelf that broke off particularly susceptible to the incoming waves from the tsunami. Here’s how Kelly Brunt, the Goddard scientist who made the discovery, explained it in her Journal of Glaciology paper [pdf]. The bolding is mine.

The recent calving from the Sulzberger Ice Shelf suggests that, while the rifts provide the ice-shelf front with a zone that is weakened with respect to stress, and while tsunamis arrive episodically to cause vibrational disturbances to these rifts, some additional enabling condition must be satisfied before a given tsunami can lead to the detachment of an iceberg.

The timing of the earthquake and tsunami in Japan coincided with the typical summer sea-ice minimum (Zwally and others, 2002). As observed in the MODIS imagery and confirmed in the ASAR imagery, the region north of the Sulzberger Ice Shelf was devoid of either fast or pack ice at the time of predicted arrival of the tsunami. Fast ice is an important factor in ice shelf stability (Massom and others, 2010). Additionally, the absence of sea ice meant that the energy associated with the tsunami incident on the ice-shelf front was not damped by sea-ice flexure. With a distant tsunami source, over an irregular ocean bathymetry, and taking into account the dispersion of high-frequency components of the tsunami outside the shallow-water approximation, a complex pattern of dispersed waves is predicted in the wake of the leading front of the tsunami (NOAA/PMEL/Center for Tsunami Research; http://nctr.pmel.noaa.gov). As these waves interacted with the ice shelf over a period of hours to days, flexural modes may have been resonantly excited, each with the potential to trigger iceberg calving (Holdsworth and Glynn, 1978), in a pattern reminiscent of the delayed response of harbors documented in the far field during the 2004 Sumatra tsunami (Okal and others, 2006).

This study presents the first observational evidence linking a tsunami to ice-shelf calving. Specifically, the impact of the tsunami and its train of following dispersed waves on the Sulzberger Ice Shelf, in combination with the ice-shelf and sea ice conditions, provided the fracture mechanism needed to trigger the first calving event from the ice shelf in 46 years

Text by Adam Voiland. Imagery from the European Space Agency/Envisat.

Thank you for this film on the Antartic Ice Shelf and the tsumani in Japan and the relatedness of the two events. I really learned a lot from the film clip and the article.

O MY!