Field assistants tromped through bogs in Harriman, NY to collect sediment cores that NASA

scientist Dorothy Peteet is using to date the retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Credit: Peteet

I spent big chunks of my childhood mucking through the lakes and bogs of New England with my brothers and looking for any number of critters hidden in the silt.

Turtles, of course, were the main draw (minus the snappers, which we knew were capable of mangling a toe or finger with a passing chomp), but actually snagging one always was a rare treat. Bullfrogs, salamanders, and newts were our standard catch.

If only we’d had a microscope. Watching Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) botanist Dorothy Peteet show images of tiny fragments of pollen, seeds, and fossils that settled to lake bottoms and sat largely unchanged for thousands of years reminded me of the extraordinary oddness–and beauty–that’s lurking in the most unsuspecting of places.

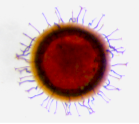

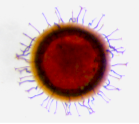

Look, for example, at this fossilized head shield of a daphnia, or water flea, which Peteet showed during presentations at GISS and the American Geophysical Union meeting last December. It’s a miniscule planktonic crustacean with a transparent body and a heart that beats visibly:

Or this statoblast, a peculiar little reproductive pod that can withstand desiccation and freezing and buds from aquatic creatures called bryozoans:

Or this one, a fossilized leaf of a fruit-bearing, cold-loving tundra plant, perhaps a blueberry:

Peteet isn’t poking around in the mud just for fun like my brothers and I did as kids, though. She’s collecting bog cores and scrutinizing the bits of fossilized plants and animals, which can be dated quite precisely using radiocarbon techniques, that turn up in the cores. Her goal is to pinpoint the timing of the collapse of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, a massive block of ice that stretched as far as Long Island during the peak of the last ice age. With Arctic ice currently undergoing rapid retreat, sorting out how the Laurentide Ice Sheet collapsed has big implications for understanding how climate change might proceed.

By analyzing material from some of the first creatures to colonize glacial lakes after the ice retreated, such as those water fleas, Peetet can estimate the date the ice sheet collapsed. Her findings suggests that the collapse occurred about 15,000 years ago, which would put it five-to-ten thousand years later than other dating techniques (particularly one influential technique that involves dating the beryllium from boulders dropped by the retreating ice sheet).

“This was surprising, and it’s generated some controversy,” she told her colleagues. “I’d like to have your ideas about what’s going on.” To learn more about the topic, you can watch, listen, or view a pdf of Peetet’s full presentation here.

Share your stories about exploring the muck in your neighborhood, your ideas on the dating controversy, and we’ll make sure that Peteet sees them and posts a reply.

Botanist Dorothy Peteet

Botanist Dorothy Peteet

–Adam Voiland, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

One-sixth of the world’s population relies on melted snow for their freshwater, which means good estimates of snow are critical for making realistic predictions of a region’s water supply.

One-sixth of the world’s population relies on melted snow for their freshwater, which means good estimates of snow are critical for making realistic predictions of a region’s water supply.

jpg.jpg)