It seems to be entirely appropriate that a vessel like ET-134 must first cross the Gulf of Mexico, a body of water rich in the history of exploration, in order to reach its launch site at Kennedy Space Center and make the exploration of space by the space shuttle crews possible; a sea voyage to make possible a space voyage.

From 2004, Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor (SeaWiFS) image of the Gulf

of Mexico. Around the circumference of the Gulf, the outflow of several rivers is visible

in colorful swirls that are probably a mixture of sediment, dissolved organic matter,

and chlorophyll from algae and phytoplankton in coastal waters. Credit: NASA/

Goddard Space Flight Center/SeaWiFS Project/ORBIMAGE

View all blog images in this Flickr gallery

Great explorers, mostly Spanish, came this way before. Ponce de Leon, Hernando Cortez, Fernandez de Cordoba, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, Hernando De Soto are among the explorers who either crossed the Gulf to Mexico or sailed along its shores in search of new territory or riches. The French explorer Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle descended the Mississippi River via Illinois and discovered the Mississippi Delta and claimed what is now Louisiana for France. The waters of the Gulf, like the St. Lawrence River to the north, have played a very significant role in making the exploration of the Americas possible, especially North America.

The Gulf of Mexico is the ninth largest body of water in the world; a playground for millions of vacationers each year and an important crossroads for trade and maritime commerce for the United States, Mexico and the northern tier countries of South America. At any one moment www.marinetraffic.com will display several hundred tugs, tankers, freighters, passenger ships and privately owned pleasure craft sailing the Gulf or in port along its periphery.

The Gulf is actually a tiny inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, or an ocean basin pretty much surrounded by the North American continent and the island of Cuba. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, my stomping grounds for my entire adult life, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. The shape of its basin is roughly an oval and is approximately 810 nautical miles (1,500 km) wide. Almost half of the basin is relatively shallow waters, but its deepest waters are 14,383 ft (4,384 m) called the Sigsbee Deep, an irregular trough more than 300 nautical miles (550 km) long.

Aerial image of islands in the Mississippi Sound. Credit: NASA

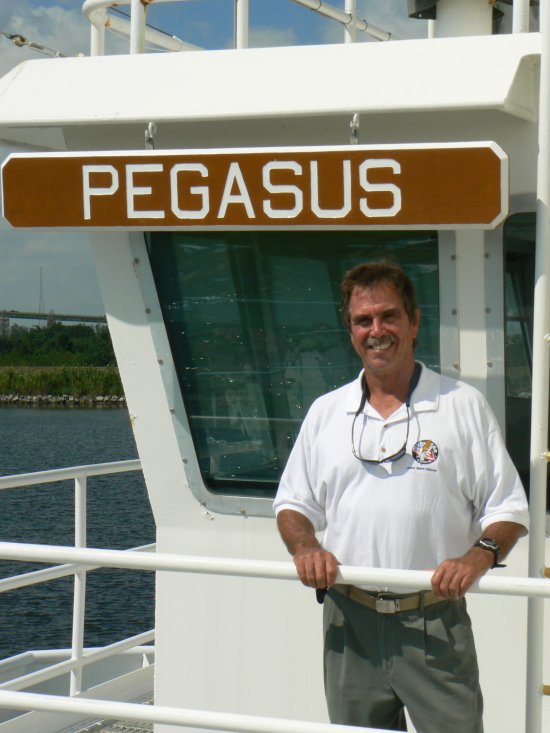

Liberty Star and Pegasus and of course ET-134 passed outbound between Cat Island and West Ship Island and will cross the Gulf more or less on a direct path from Gulfport, Miss., to the Straits of Florida, steering around the Dry Tortugas Islands and Key West. The weather ahead of us today is predicted to be good, with seas of 2–3 feet and winds generally out of the SSW at 10 knots. We expect a quiet and uneventful passage at an average speed of 9 knots as the crew bends to a routine of performing its normal duties of running and maintaining the ship and resting when possible; routine duties performed by a ship underway by a crew in much the same way sailors have done in these waters for hundreds of years.

We passed West Ship Island to our east, home to beautiful beaches, via a local ferry from Gulfport, and home to Fort Massachusetts. The fort and its many siblings such as Fort Macomb, which we have already passed in the Intracoastal Waterway, and the fort system that we find along the length of the Gulf Coast and Atlantic seaboard were envisioned to serve as a bulwark against enemy invasion fleets. During the War of 1812 enemy fleets successfully deposited armies within striking distance of Baltimore and the nation’s capitol and in 1815 troops landed south of New Orleans, right on the doorstep of modern day Michoud Assembly Facility.

Construction of Fort Massachusetts began in June 1859 under supervision of the Army Corps of Engineers and by early 1861 the outside wall of the fort had taken shape.

In January 1861 Mississippi seceded from the Union, occupied the fort and precipitated one of the first actions of the Civil War in the state. On July 9, the Union ship Massachusetts came within range of the Confederate guns and a brief fight occurred, resulting in few injuries and little damage to either side. The action was the only military engagement in which Ship Island or the fort was ever directly involved.

Union forces occupied the island as a staging area for the Union forces’ successful capture of New Orleans in the spring of 1862. As many as 18,000 United States troops were stationed on Ship Island. The island’s harsh environment took its toll on many of the men. More than 230 Union troops eventually died and were buried on Ship Island during the Civil War. The bodies of many of these men were later reburied at Chalmette National Cemetery near New Orleans.

The Gulf of Mexico is literally strewn with history. In 1492 only a short distance from the Gulf Spain’s Santa Maria, Pinta and Nina sailing under Christopher Columbus went ashore and began an incredible era of exploration of the Western Hemisphere. Spanish, English, French, and Portuguese explorers came this way in the 1500s and beyond. Later, Spanish galleons loaded riches and treasure in Cartagena (modern Columbia), sailed for Spain aiming across the Gulf for passage either through the Florida Straits or the passages through the Leeward Islands, or perhaps skirting along the northern coast of South America, hoping to avoid storms, privateers or pirates.

The Monsters of the Gulf

The Gulf is not considered particularly hostile most of the year. But the Gulf is the feeding ground of the greatest breed of sea monster on Earth; monsters that literally rise from the surface feeding on the warm waters of late summer and early fall, pulling massive amounts of energy skyward like ocean-going demons. Throughout much of history, they remained unnamed. Today we remember and know their names very well. These are the hurricanes.

The English word for hurricanes was adopted from the Spanish word huracon which in turn was adopted from a similar word for storms used by the Arawak language of the Caribbean region. Spanish explorers, who knew well the dangers of sailing the north Atlantic, apparently were taken somewhat by surprise by the ferocity of storms in the Caribbean and Gulf and European explorers lost many valuable ships and sailors throughout the region.

In recent years space explorers, NASA and international partner astronauts, on board the International Space Station, have provided hundreds of images of hurricanes from their position of relative safety some 200 miles overhead. Among those images is one of Hurricane Ike just about to hit the Texas and Louisiana coast, its massive Cyclops eye, staring back into space at the astronauts.

Hurricane Ike. Credit: NASA

Plowing their way across the mid Atlantic from the west coast of Africa as tropical depressions and later as tropical storms, hurricanes gather their strength, bide their time and spin up for the final dash to land. They often turn north to die in the colder Atlantic; they often plow ahead into the Greater Antilles like Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, the Bahamas and Cuba, where they ravage the much too often ravaged. They may drive straight north into Florida proper or… they may spin their way into the Gulf, where their strength builds and towers to tens of thousands of feet of unbridled energy and then, when ready, advance relentlessly to the coast.

Waiting on shore is a host of vulnerable victims including the coastal cities of Mexico, Corpus Christi, Galveston, Houston, New Orleans, Lake Charles, Biloxi, Gulf Shores, Pensacola, Mobile, and cities east along the coast to Tampa/St. Petersburg.

Three NASA facilities lie in their possible path; the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, where space missions are controlled; the Stennis Research Center in Mississippi where space shuttle main engines and propulsion systems are tested, and the Michoud Assembly Facility in East New Orleans where external tanks like ET-134 are assembled. In 2008 Michoud was narrowly missed by Hurricane Gustav and Johnson Space Center was damaged by Hurricane Ike. NASA does a great deal of planning to be ready for these monsters and to protect its employees.

In 1900 a hurricane came ashore with no warning in Galveston and killed 6,000. In 2008, Ike took more lives in Galveston, but not near as many as in 1900. Carla hit Texas in 1961 with 140 mile-per-hour winds; Camille hit Mississippi in 1969 with 190 mph winds; Frederic rolled over Alabama in 1979, smashed up Gulf Shores and knocked down my television antenna in Tuscaloosa 300 miles from the coast; Opal hit the Florida panhandle in 1995 with 115 mph winds; Andrew hit Louisiana in 1992 with 115 mph winds; Ivan hit Alabama and the Florida panhandle in 2004 with 120 mph winds. In 2005 Dennis hit the Florida panhandle with 120 mph winds; Katrina hit Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana in 2005 with 125 mph winds and caused the deaths of 2,000 and massive damage; and also in 2005, Rita followed Katrina to hit Texas and Louisiana. Depending on the source, since 1900 hurricanes have killed 9,000 and taken hundreds of billions in property on the Gulf Coast.

Two of the publics’ guardians providing advance warning against hurricanes are located nearby along the Gulf Coast, the United States Air Force 53rd Weather Recon Squadron “Hurricane Hunters” is located at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Miss. and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration aircraft operations center is located at MacDill Air Force base, Tampa, Fla.

What does Liberty Star do if a hurricane is on the horizon? Liberty Star quickly gets out of the way or does not sail at all — Liberty Star with its VIP precious cargo on board Pegasus will take no chances with the untamed and unpredictable monsters of the Gulf.