Geeked on Goddard’s Dan Pendick offers up an eerie “What On Earth is That” sound for Halloween. As always, post your guesses in the comments, and check back next week for the answer…

What On Earth is That?

Geeked on Goddard’s Dan Pendick offers up an eerie “What On Earth is That” sound for Halloween. As always, post your guesses in the comments, and check back next week for the answer…

What On Earth is That?

Live television from the A-Train symposium in New Orleans courtesy of the unscripted, unpredictable, and always entertaining folks from NASA Edge. Watch the full show here.

In July 2010, monsoon rains came to Pakistan in a Biblical way. Three months’ worth of rain fell in just one week. Historic flooding ensued in the weeks to follow — spanning 600 miles along the flood zone of the Indus River Valley — taking the lives of as many as 1,600 people. The flood waters also displaced as many as 20 million.

If only the warnings of historic flooding had come more swiftly and more accurately, it’s possible some of those who perished could have lived to tell about it. Countless numbers of the nearly 2 million homes destroyed might still be standing. And relief aid to refugees of the floods might have reached villages in need with greater precision and speed. If only…

Humanitarian aid efforts in the months after the flooding have been generous, but have paled in comparison with Haitian earthquake relief, and the world’s response to the aftermath of the 2004 Asian tsunami. But, additional assistance continues to arrive. In at least one instance that assistance hails in part from an unconventional source – NASA — with a native son of Pakistan leading the charge.

Growing up in a rural mountainous area near Gilgit, Pakistan, Sadiq Khan never experienced first-hand any of the devastation that more often than not wreaks havoc on the country’s densely populated, lower lying regions like Punjab and Sindh. But, a few years following the untimely death of a friend in the 2005 earthquake that killed upwards of 85,000, Khan, a graduate research assistant at the University of Oklahoma (OU), along with associate professor Yang Hong of the school’s Remote Sensing Hydrology Group, developed a proposal to build Pakistan’s capacity to reduce the risk of life and agricultural damage during natural disasters. And a specific proposal focus – developing an early warning system for flooding – would prove serendipitous.

On the heels of the catastrophic floods, Khan and Hong received a half-million dollar grant in August for their three-year project from the Pakistan – U.S. Science and Technology Cooperation Program that Pakistan’s government and the U.S. Agency for International Development are funding. Of the 28 projects (out of 270 applications) chosen for funding, Khan’s ranked as the most relevant to society.

“Pakistan has been limited by a lack of human resources, training for personnel, and data availability,” said Khan, who is also a 2008-2011 NASA Earth Sciences Graduate Fellow. “So, the reliability of the current flood-warning system in Pakistan is poor, and likely the reason flood mortality was unusually high. They’re using an older generation of hydrologic models, probably from the 1980s, that don’t require remote sensing data.”

So, where does NASA come in? Well, Khan, NASA collaborator Shahid Habib, head of applied sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and other colleagues will work to train Pakistani scientists to access and use free data from several of NASA’s remote sensing satellites in what are called predictive hydrometeorological models. These models can improve the ability to forecast floods accurately and with more warning time.

So, where does NASA come in? Well, Khan, NASA collaborator Shahid Habib, head of applied sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and other colleagues will work to train Pakistani scientists to access and use free data from several of NASA’s remote sensing satellites in what are called predictive hydrometeorological models. These models can improve the ability to forecast floods accurately and with more warning time.

Starting in mid-November, Khan and others will begin three years of training researchers at the National University of Science and Technology in Islamabad to use a flood model they developed at OU in collaboration with NASA that makes use of a lot of NASA data.

They’ll use precipitation data from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission satellite, because heavy rain causes most of flooding. The model also uses a whopping amount of other NASA remote-sensing information: digital elevation (Digital Elevation Model), topographical (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission), radiometry (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer), and land cover data (from an instrument aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites), as well as soil moisture estimates from Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer – Earth Observing System Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer – Earth Observing System.

“The plains agricultural regions – the ‘bread basket’ of Pakistan – suffered extreme damage in the floods and the deaths were heartbreaking,” Khan explained. “So, it’ll be an honor for me to go back home, visit affected areas that are home to more than 100 million people, evaluate needs, and work with my government to create a 21st-century flood-warning system that can prevent this level of suffering from flooding from occurring again.”

— Gretchen Cook-Anderson, NASA’s Earth Science News Team; Images courtesy of the NASA Earth Observatory (top) and Sadiq Khan (bottom).

Each afternoon, some 705 kilometers (438 miles) above the surface, a parade of Earth-observing satellites soar across the equator. Chances are you’ve never heard of them since the close-flying satellites keep a far lower profile than, say, attention hogs like Hubble or the International Space Station.

Four satellites — Aura, CALIPSO, CloudSat, and Aqua — make up the A-Train today. Three more — Glory, OCO-2, and GCOM-W1 — are slated to join by 2013. The train of satellites — some flying just about 15 minutes from one another — cross the equator at 1:30 PM each afternoon. (That, in part, is why there that “A” in the name; A stands for “afternoon.” Less known is the fact that it was a NASA earth scientist who helped coin the name as a reference to Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train” jazz standard, which became a signature tune of the Duke Ellington orchestra.)

Want to find out more? Well, you can try to spot the A-Train satellites with a pair of binoculars or powerful telescope (though they’re not particularly bright). You can track the trajectory of A-Train satellites in real time on websites such as this. (Here’s Aqua, for example). Or if you’re feeling ambitious, you can slog through A-Train data on Goddard’s A-Train Data Depot. This excellent Physics Today article has some good A-Train info, as does NASA’s A-Train website and that of the 2nd A-Train symposium, which kicked off in earnest this morning in New Orleans.

But, my advice: kick back, crank up the volume on Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald to get yourself in an A-Train state of mind, and just watch the satellites zip around the planet in the animations above and below. The bottom set shows what the A-Train will look like when Glory joins; the top set shows A-Train measurements of Tropical Storm Debbie.

Look Up

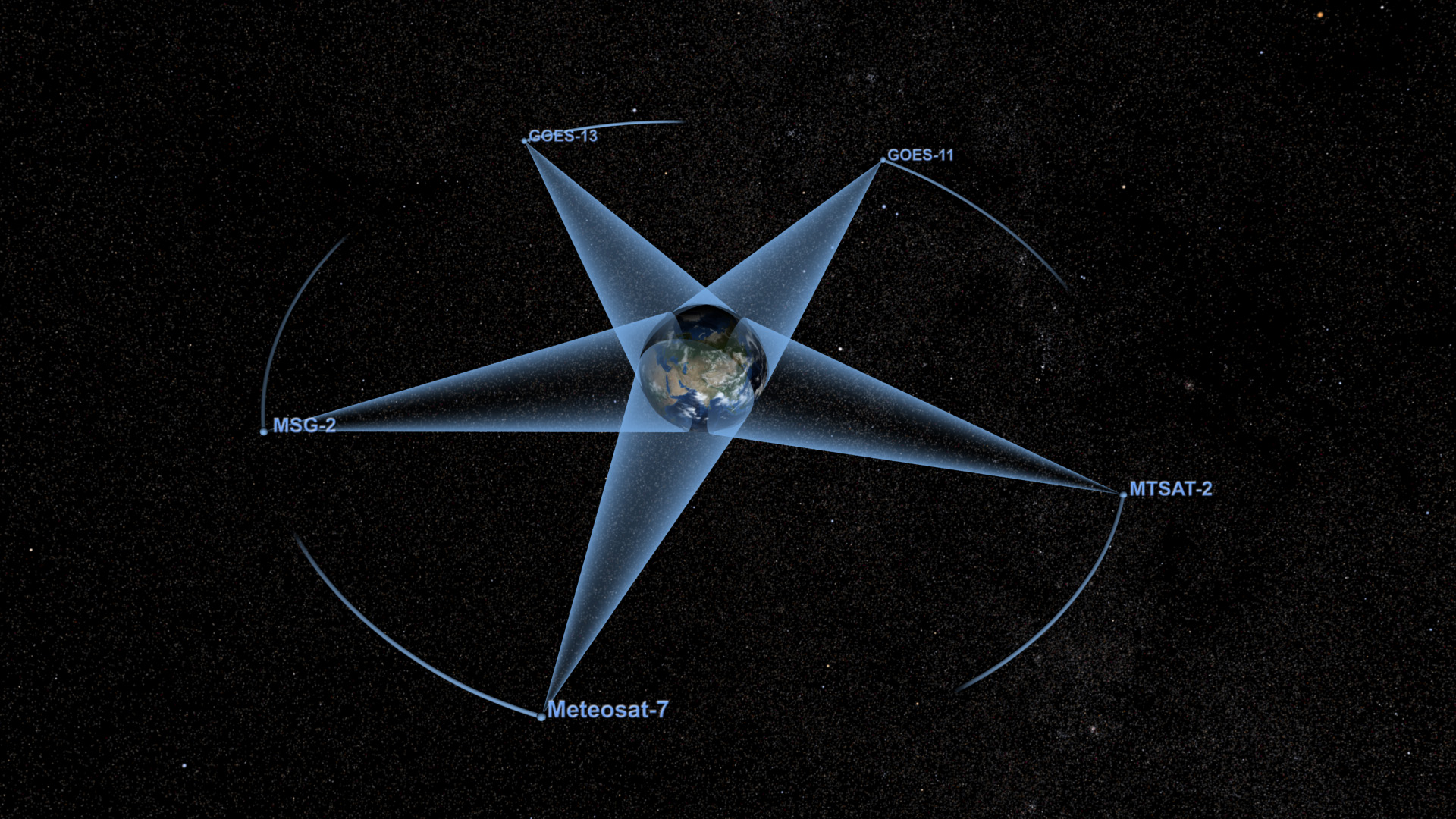

Fabulous new animation shows orbital paths of weather satellites. (GSFC SVS)

Antarctica, Here We Come

Operation IceBridge heads to Chile to begin a new phase of its campaign. (NASA Explorer)

Solar Spectral Stumper

Every now and then Nature throws scientists a curve ball — such as (ifthey turn out to be right) these provocative finding about the sun’sspectral irradiance. (RealClimate)

Sorry, Water Vapor

It’s actually carbon dioxide that controls Earth’s temperature. (NASA.gov)

Food For Thought

Ten things you probably don’t know about Earth. (NASA Global Climate Change)

Get On Board

Scientists from across the country are prepping for next week’s A-Train meeting in New Orleans. (Langley)

Fire Breathing Storms

Pyrocumulonimbus: the fire-breathing dragon of clouds. (Langley)

Tweet of the Week

Whoa, the sun just got mooned! SDO Observed its First Lunar Transit HD Video here: http://bit.ly/djeEnU & #photo here: http://bit.ly/d8Wc8l (NASA_GoddardPix)

–Adam Voiland, NASA’s Earth Science News Team, Image courtesy of Goddard Space Flight Center’s Scientific Visualization Studio

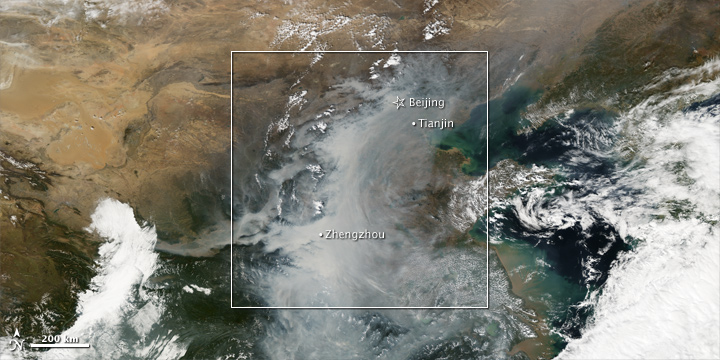

This spectacular cloud of smog and haze formed over eastern China last week when a high-pressure weather system moved in to the area, allowing industrial and burning byproducts to settle with little disturbance from winds. As NASA’s Earth Observatory reported, NASA satellite instruments detected extremely high levels of sulfur dioxide, which most likely came from various industrial processes such as coal-burning power plants and smelters (facilities that melt or fuse ores in order to extract usable metals).

Satellites also detected high levels of aerosols — most likely sooty black carbon or organic carbon particles from wildfires and fossil fuel burning – that absorb sunlight and “trap” heat. In fact, the air was so thick with the light-absorbing particles at times that seeing the midday sun clearly would have been difficult. Bearing this out, news media reported numerous traffic accidents associated with the lack of visibility.

How does this event fit into broader pollution trends in the region? A study published earlier this year in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics offers some insight. The authors, which included a researcher from Goddard Space Flight Center, analyzed sulfur dioxide emission trends in China since 2000 and made a number of notable observations. These included:

Want more details? You can read the full paper here [PDF].

–Adam Voiland, NASA’s Earth Science News Team, Image courtesy of NASA’s Earth Observatory

Kick back, make yourself some popcorn, and enjoy one of the latest offerings from NASA Television: a tongue-in-cheek trailer about the horrors of airborne particles called aerosols. Black carbon plays the villain, and it’s this sooty particle (which comes from wildfires, campfires, various industrial processes, and diesel fumes) that gets the blame for “cursing” atmospheric scientists with a “scourge of ignorance”.

Plenty of specialists here at Goddard Space Flight Center will tell you that, over the years, we’re making real progress understanding aerosols, but there’s little doubt that the tiny airborne droplets and particles have given climatologists headaches over the years.

Back in March of 2009, James Hansen, director of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, laid out the key obstacles underpinning what he called the “Nasty Aerosol Problem” in a presentation he gave in Copenhagen. As he puts it in one slide:

* “We do not have measurements of aerosols going back to the 1800s – we don’t even have global measurements today.

* Any measurements that exist incorporate both forcing and feedback.

* Aerosol effects on clouds are very uncertain.”

NASA’s upcoming Glory mission, which carries a promising new gizmo for studying aerosols called the Aerosol Polarimetery Sensor (APS), looks to be our next best shot for getting a better handle on the problematic particles. Glory is hardly the only NASA effort addressing aerosols, but I’ve certainly noticed that nothing rivals a satellite mission (as opposed to, say, ground or aircraft campaigns) when it comes to generating buzz in the hallways.

You can learn more about Glory here, here, and here. And why not follow Glory on Twitter or Facebook?

–Adam Voiland, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

If I’ve learned anything as a science writer, it’s that scientists produce such a flood of fantastically odd factoids that boredom isn’t much of an occupational hazard. Heck, the chances that deep boredom will strike during work are right down there with the odds a cataclysmic disaster will obliterate humanity come 2012. (Pretty much impossible, in other words.)

I got a healthy reminder of this last week when a bug expert—an entomologist, in proper scientific parlance—by the name of Benoit Guenard turned me on to some photos of a truly bizarre genus of ant called Myrmecocystus. A slice of one of those photos—a group of jaw-droppingly obese honeypot ants hanging from the roof of a nest—became our most recent “What On Earth is That?”

This particular type of ant, which lives in deserts, is like something out of The Matrix. When food is plentiful, honeypot colonies select certain workers—entomologists call them repletes—to serve as food receptacles for the group. The other workers tuck the repletes away in a safe spot, and then literally stuff them with food until the back sections of the repletes literally swell up like water balloons.

Grape-sized repletes so fat they cannot walk are common. When food gets short, hungry workers just wander over to a replete, poke and prod it a bit, and wait for it to upchuck lunch. If that’s not bizarre enough, it turns out that rival honeypot ant colonies have a habit of raiding one another and plundering–then enslaving–repletes. Stranger yet, it’s not just ants that have a taste for repletes; they’re something of a local delicacy among certain tribes in Australia.

What on Earth is That?

(Post your guesses in the comments. Check back next week for the answer…)

Here’s the question from last time

And the time before that

And that

And…