Each summer, sandstorms lift millions of tons of dust from the Sahara, carrying plumes of it off the West Coast of Africa and over the Atlantic Ocean. Eric Wilcox, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, has been using data from NASA satellites to examine the impact such storms can have on rainfall patterns. Wilcox has a new paper about his findings in Geophysical Research Letters; Nature Geoscience also highlighted it in a recent issue. As a result, we sat down with Wilcox to discuss his new findings and some little-known details about dust.

WhatOnEarth: How does dust affect the atmosphere?

Wilcox: Well, we know that dust isn’t just a passive particle floating around. We know it can either absorb or scatter sunlight. Dust outbreaks surely cool the planet by reducing the amount of sunlight that reaches the surface. Likewise, we know dust can warm the atmosphere, although the magnitude is still uncertain.

WhatOnEarth: What causes a particle to absorb rather than scatter light?

Wilcox: It has to do with the color of the particle and, to some degree, the shape. We call this property the single scattering albedo, which is the probability that a photon of light will scatter versus getting absorbed. If the scatter is very high—say 0.99—then we’re confident that 99 out of 100 photons will scatter. If it’s lower, say 0.85, that means there’s a 15 percent chance that the proton will be absorbed.

WhatOnEarth: Where does Saharan dust fit in?

Wilcox: Some Saharan dust is quite bright and some is much darker. It depends on where the sand is coming from and what its mineralogy is like.

WhatOnEarth: Why does it matter if dust is absorbing light?

Wilcox: We’ve found that dust outbreaks, along with other factors, seem to be shifting tropical precipitation (which typically occurs in a narrow band where winds from the northern and southern hemispheres come together) northward by about four or five degrees, which is about 240 to 280 miles at the equator.

WhatOnEarth: Really? What does dust have to do with precipitation?

Wilcox: The main pathway for dust off the Sahara is usually well north of the band of tropical Atlantic rain storms. However, dust storms coincide with a strong warming of the lower atmosphere, so the atmospheric circulation over the ocean responds to that warming by shifting wind and rainfall patterns northward during the summer. The rainfall responds to the passage of a dust storm even if the dust does not mix with the rain.

WhatOnEarth: Will the upcoming Glory mission help you study this phenomenon? I know it has an instrument that will measure aerosols such as dust?

Wilcox: Definitely. Over bright reflective surfaces such as deserts — where it has been nearly impossible to distinguish aerosols from the surface — we’re at the point that any new information will be helpful.

WhatOnEarth: What’s the significance of a northward migration of rainfall during dusty periods?

Wilcox: Certainly people local to the area have an interest in understanding how dust affects their rainfall patterns. The finding also lends support to an idea from one of my colleagues—Bill Lau—who studies the elevated heat pump.The idea is that aerosols from dust storms and air pollution actually affect monsoons. Space Flight Center.

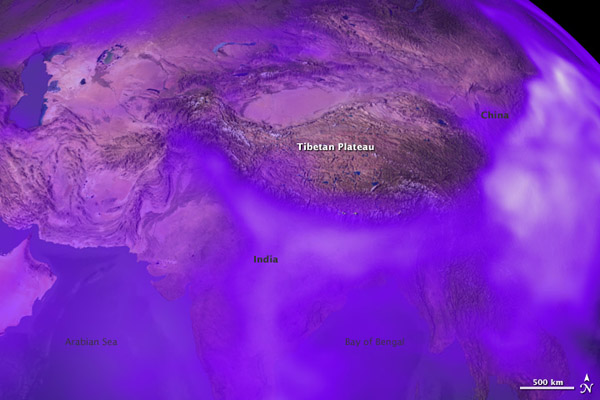

Image Details: The lead image was acquired by the MODIS Land Rapid Response Team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in 2004.

— Adam Voiland, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

.jpg)