Drew Shindell (left), Veerabhadran Ramanathan, and Tami Bond speak with Representative Edward Markey after the three scientists testified. Credit: NASA/Voiland

Leading aerosol scientists, including NASA’s Drew Shindell, explained the intricacies of a sooty component of smoke called black carbon to members of the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming during a hearing on Capitol Hill last month.

Their message: controlling black carbon emissions could be a win-win for both human health and the environment.

Not only can partially combusted particles of carbon lodge in the human respiratory system and cause disease, the panelists explained, they also contribute to climate change by warming the atmosphere and changing the way Earth reflects sunlight back into space.

Three lawmakers—Representative Edward Markey (D-Mass.), Representative Jay Inslee (D-Wash.), and Representative Emanuel Cleaver (D-Mo.)—questioned the scientists.

Tami Bond, a black carbon specialist from the University of Illinois, began the hearing by offering a summary of black carbon’s potent short-term climate impacts. She noted, for example, that:

• One ounce of black carbon absorbs as much sunlight as would fall on an entire tennis court.

• A pound of black carbon absorbs 650 times as much energy during its one-to-two week lifetime as one pound of carbon dioxide gas would absorb during 100 years.

• An old diesel truck driving 20 miles would emit about one-third of an ounce of black carbon and 70 pounds of carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide from that truck would have five times the warming power of the black carbon, but it would spread out over 100 years. The truck’s more potent black carbon impact would have an effect in the span of a few weeks.

Drew Shindell, a climate modeler from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York City, provided more details about where black carbon comes from and how much impact it has on Earth’s climate.

As seen in this scanning electron microscope still image, small chain-like aggregates of soot cling to larger sulfate aerosol particles. Credit: Arizona State University/Peter Buseck

Diesel vehicles, agricultural burning and wildfires, and residential cooking stoves are key sources of black carbon. However, combustion that occurs at higher temperatures — such as the type that takes place in power plants — does not produce much of the substance.

Shindell said climate models from NASA GISS and elsewhere show that 15 to 55 percent of global warming is due to black carbon. The wide range is primarily because of incomplete knowledge about how black carbon and clouds interact.

One of the more interesting questions came from Rep. Inslee, who asked the scientists whether black carbon’s impact is due to the fact that it absorbs sunlight and warms the atmosphere, or because it covers snow and ice with dark soot, which reduces Earth’s albedo and makes the planet less reflective.

Veerabhadran Ramanathan , a professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, responded: “The albedo effect contributes about 10 percent of the total black carbon effect. But if you look in the Arctic or in the alpine glaciers, then the darkening effect may be the dominant effect.”

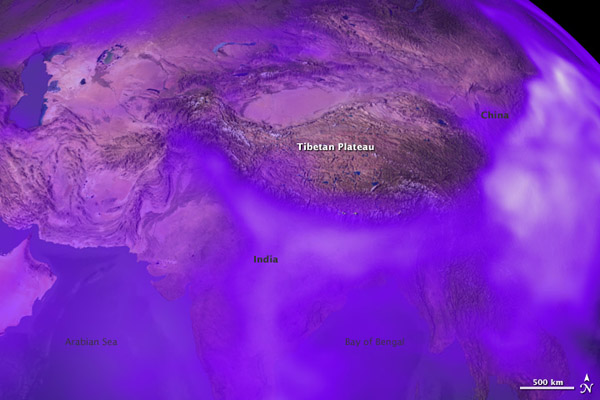

Shindell added that the scientific understanding of black carbon’s impact varies by region. “In places like the Himalayas, the results are somewhat ambiguous,” said Shindell. Over Himalayan glaciers, large amounts of dust — which also absorb radiation — and other pollutants in the air may dampen the effect. “In the Arctic, which tends to be very far from dust sources, the snow is very clean, so the effect is extremely large.” Increasing levels of black carbon combined with decreasing levels of sulfates may account for more than half of the accelerated warming in the last few decades, Shindell’s research suggests.

Inslee also expressed frustration about the lack of understanding of science and climate change among his fellow lawmakers.”If I was scientist and I knew what was going on out there, I’d be in somebody’s grill, telling them we need action,” he said. “And yet you just don’t see that from the scientific community….Why doesn’t that happen? Should it happen?”

Drew Shindell testifies as Veerabhadran Ramanathan looks on.

Credit: Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming

The scientific method and the culture of scientists, Bond replied, makes it very difficult for scientists to lobby lawmakers or advocate a policy position and remain credible. “This is a difficult question and has to do with the nature of scientists and how they approach science,” she said. “If you have an action outcome, one is almost afraid that you’ll affect the science because you’re supposed to look at it dispassionately. How we conduct our business, 99.9 percent of the time, we must step back from what we want the outcome to be. We’re not allowed to want an outcome.”

— Adam Voiland, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

WoE:

WoE:

.jpg)