In today’s A Lab Aloft International Space Station Chief Scientist Julie Robinson, Ph.D., looks back on 2014 to highlight some of the year’s milestones and research achievements.

As I take a moment to reflect on the accomplishments of the past 12 months, I can’t help but think of how they relate to where we’re going next with the International Space Station. From the crew capabilities to research goals, from NASA’s plans for continued exploration to the benefits for humanity from station studies, there are some key areas that stand out from 2014.

During the last year there has been so much demand for research on the space station—including investigations that require crew time—planners really have had to push the schedule. We deferred some preventative maintenance, scaling back on some filter changes, for instance, to adjust operations for increased crew time for research. That’s allowed us to get as much as 47 hours a week averaged in a six-month period. This number is the total for the three U.S. astronauts, rather than the original standard of 35 hours for science. When you think about it, that’s almost half again as much research as the designed schedule.

This is a great performance of balancing time aboard station, though we won’t always be able to hold to that. This is why we still need to go to seven crew members. The crew dedicating time to tend to investigations helps us to optimize the research coming out of space station, as well. Currently we house six crew members in orbit aboard the space station, and some of you may know that this is one person short of the craft’s design to sleep seven. This is because our Soyuz “lifeboat” can only return six crew members in an emergency. The advent of commercial crew will allow us to expand by that extra crew member, as the new vehicles can ferry four. This is a future goal that we all look forward to: a full house.

The crew was particularly busy during the latter part of 2014 with a huge new capability for biological research using model animals. This also was driven by user demand to launch rodents—meaning mice and rats, though so far we’re starting with mice on the space station. We now have a system that can launch rodents aboard the SpaceX Dragon vehicle. The animals can live aboard station for a long period of time in special habitats, and then either be processed on orbit or eventually returned live. This system was important to get online this year, because we had a large number of users in medical research and pharmaceuticals interested in using space station as a test bed for their studies.

There are many discoveries that have affected human health that were dependent on the use of animals as what we call “model organisms,” from the discovery of insulin to the that of tamoxifen to treat breast cancer to kidney transplants. This doesn’t mean these organisms are going to grace the cover of a magazine, but rather that they provide a model for humans to help us understand disease processes. By watching how they respond to research, we can in turn learn how to fight those diseases.

Having the ability to fly mice to space for long-duration studies is a huge advance. Fulfilling this capability was our response to the Decadal Survey recommendations of the National Academy of Sciences. We have years of research already lined up hoping to get access to these mice. To optimize the potential for discovery, we combine as many experiments together on this precious resource as possible.

This is an exciting area of study, as just a handful of mice have flown in the past—both on space station assembly flights and one flight in a system called mice drawer system. Even so, those findings account for a significant number of our highest profile publications from space station research. With access twice per year, we now have this type of study as a routine capability. This means we can expect to see a huge ramp-up in high-impact research in biomedical areas.

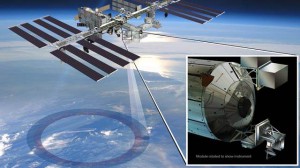

Another big change this year has been the space station maturing as a platform for Earth science. My colleagues in Earth sciences at NASA have called this the year of the Earth, because they’ve had five related instruments go into space this year. That’s a record, and two of these are on the space station, a first!

Moving forward we’re going to see a couple instruments a year go up until the space station’s current external sites are primarily full, likely in 2017. We now need to study whether to grow our capabilities to support more Earth sciences instruments, as well as astrophysics and heliophysics studies.

It’s really thrilling to see these initial instruments come to station and begin operations right off the bat. The first of these, ISS-RapidScat, was bringing hurricane data home within three hours—this was less than a week after installation. The instrument measured the sea-surface winds and was used to look at Typhoon Vongfong in Japan. How quickly scientists can use these data and incorporate findings into use for us on the ground can provide real benefits. The results can give valuable information that people need to know to protect their lives and property, making it an important advance to have available aboard station.

Next is the Cloud-Aerosol Transport System (CATS), an imager that looks at clouds and aerosols for climate research. CATS will be followed by a number of instruments that are either brand new to science or that fill a gap from similar satellites to provide cross calibration. Our understanding of the Earth is going to improve thanks to the research from all of these instruments.

One of the areas that congress has encouraged us to pursue is the development of commercial applications and commercial research on the space station. To this end, they declared the space station U.S. segment a national laboratory in 2005. In 2011 we selected CASIS, the Center for Advancement of Science in Space, to manage that national lab side for use by researchers that are not funded by NASA. These scientists may be funded by other government agencies or the private sector or nonprofit organizations.

This year CASIS grew substantially with the advent of their ARK-1 and ARK-2 suites of investigations aboard station. Also in 2014, the first National Institutes of Health (NIH) investigator of the space station national lab era launched her immunology research study. There are other NIH studies to come, including one that looks at bone loss. CASIS also brought large initiatives in protein crystal growth, Earth sciences, stem cells and materials science to continue to advance commercial research aboard the space station.

I recently spoke with Brian Talbot, marketing and communications director with CASIS, and he shared his thoughts with me on the accomplishments of the organization for the past year. “The continued growth of CASIS as an organization in 2014 speaks to the limitless opportunities commercial and academic researchers see aboard the space station. Through funded solicitations in proven areas of space-based research to innovative and non-traditional commercial users, CASIS is moving ever closer towards its goal of fully utilizing of the national lab for Earth-benefit inquiry.”

When I talked about crew time, you may have noticed that it was broken down by U.S. and Russian segments and crew members. While this division is useful for tracking purposes, it’s important to mention how we are blurring those boundaries. This international laboratory brings collaborations together through research that transcend relations on the ground. The space station exemplifies a global partnership at its best.

One thing that has driven us to continue advancing our partnership is the announcement of the joint one-year expedition. Since the 2013 announcement, we have made advances in finalizing our research goals in preparation for the 2015 launch. This extended expedition will have an astronaut and a cosmonaut both stay aboard the space station for 12 months, instead of the current six-month standard. It’s been decades since astronauts were in space that long. With the leaps in our medical technology, the one-year stay will help us to better understand what happens to the human body on long-duration flights. These studies also may help answer related concerns for health here on Earth.

I’m really excited about how that international collaboration across all of our partners has evolved. We’re combining more investigations, we’re releasing open data for the entire global scientific community to work with and we’re joining crew member resources to optimize all of these activities. Whether it’s microbial sampling, taking care of plants or making specific observations of the human body, our crew members are working together on what is truly an international station in space.

Early this year, John Holdren, the director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy for the Obama administration, announced their support of extending the space station to 2024. We have worked through the impacts that this has for space station research and this extension gives us 90 percent more external research and close to 50 percent more pressurized research—those studies taking place in the cabin. 2024 is very important to what we can achieve with this global microgravity resource of the space station.

When we have scientists already in line wanting to do investigations, having more time to get those studies done and even to do follow-on research opens up the discovery potential. This also provides more time for research markets to develop independently. Just like on the ground, when someone wants to study a certain area, they contract a lab to do the experiments. Someday, when space station is gone, we want scientists to have continued access through this emerging market of microgravity research in space. This longer duration for station to remain as a platform helps to open up those opportunities for researchers around the world. This is the world’s chance to continue the mission of discovery off the Earth for the Earth.

Julie A. Robinson, Ph.D., is NASA’s International Space Station Chief Scientist, representing all space station research and scientific disciplines. Robinson provides recommendations regarding research on the space station to NASA Headquarters. Her background is interdisciplinary in the physical and biological sciences. Robinson’s professional experience includes research activities in a variety of fields, such as virology, analytical chemistry, genetics, statistics, field biology, and remote sensing. She has authored more than 50 scientific publications and earned a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry and a Bachelor of Science in Biology from Utah State University, as well as a Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology from the University of Nevada Reno.