This week guest blogger Camille Alleyne,International Space Station assistant program scientist, shares her experiencesin station educational outreach with the readers of A Lab Aloft.

As I go through my busy workday, absorbed in the detailsof my part to help support the International Space Station Program ScienceOffice, I rarely stop to think about the impact the work that my colleagues andI do has on the general populace. That was until last week, when I got toexperience first-hand the power of our educational programs to inspire generations.I was invited to participate in the 10thannual Caribbean Youth Science Forum that was held in Trinidad and Tobago,my birth country. This event brought together over 300 high school seniors from6 Caribbean countries who were interested in pursuing careers in science,engineering and technology.

Participants in theCaribbean Youth Science Forum with Camille Alleyne, second right (back row).

(Image courtesy of Trinidad ExpressNewspapers/Ishmael Salandy)

Given my position within NASA, I was invited to the forumand asked to do an interactive workshop with these students on a space-relatedtopic. Suspecting that these students had very rarely, if at all, thoughtseriously about space exploration, I wanted to create an experience for them.My goal was to not only expand their minds, but motivate and inspire them tobelieve in themselves and to dare to dream big.

That is exactly what happened when the forum’s studentshad the opportunity to participate in the International Space Station Ham Radio,or ISSHam Radio, project. This investigation, which uses ham radio technology, allowedstudents to make real-time contact with the crew members aboard the spacestation for a question and answer session. The ham radio communication was anhistoric event for the Caribbean region and one that fulfilled my education objective.ISS Ham Radio is a space station educational program with a global reach, givingstudents from all over the world an ability to talk to astronauts andcosmonauts as they work and live in space.

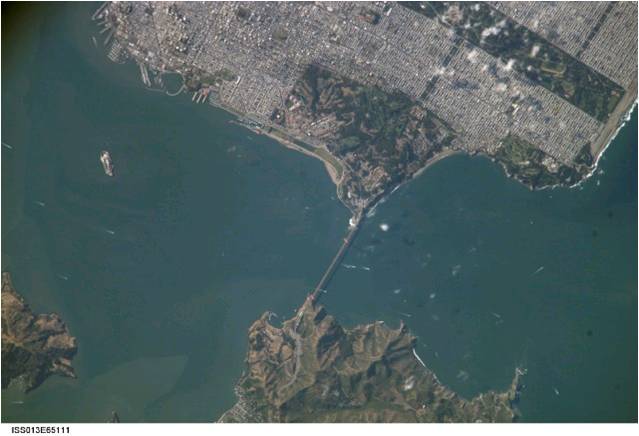

The scene during the ham radio communication included anauditorium filled with students abuzz with excitement as they waited for theactual contact to begin. The space station, on a trajectory towards SouthAmerica, was viewed on a giant screen that projected the world map and track ofthe station to help students visualize the orbiting laboratory’s location. Directcontact while the station was over Trinidad and Tobago was not possible, as thecrew would have been in their sleep period during direct flyover, so atelebridge connection was constructed. In other words, the call was scheduledto take place while the station was overhead of and able to obtain a directlink with another location—in this case, Argentina. Once established, theconnection was relayed to the Caribbean via an Argentinean ground station.

The event and contact were moderated by Steve McFarlene, amentor and radio operator based out of Canada. The Canadian team connected withthe Argentinean team over regular telephone lines in preparation for the groundstation to make the contact to the ham radio aboard the space station.

Twenty minutes before the contact, as the station enteredthe path that makes the contact possible, McFarlene gave an introduction andwelcomed the students of the region to the historic event of the first evercontact from space to the Caribbean. He asked the first student to do a test toensure a loud and clear communication. After the test, the local organizers ofevent had an opportunity to introduce themselves and the schools and studentsrepresented there. McFarlene then prompted the team from Argentina to introducethemselves. The growing excitement was palatable in the auditorium!

At precisely 11:13 EDT, McFarlene gave the go-ahead tostart the event. Organizers queued up the 12 students chosen to read theirquestions to the space station crew and then a voice came over the speakersaying “testing, testing.” It was the voice of Satoshi Furukawa, the JAXA crew memberaboard the space station—my heart skipped a beat. We had made contact!

Students asking Satoshi Furukawa their questions. Fromleft to right: Jonathan Gosyne, Presentation College Chaguanas; Adam Hanna,Queen’s Royal College; Oliver Maynard, TA Marryshow College, Grenada; andMichael Green, Deputy Director of Operations, TTARL.

(Credit: DesireeSampson/NIHERST)

The room was awed silence as the first student asked hisquestion: “Hi, I am Carlos. Howis the ISS powered and how does the station use its power source to maintainorbit? Over!” Satoshi responded and then the next student asked their question.Before an answer was communicated, something unexpected happened—the connectionwent dead! There was a gasp in the room and McFarlene announced that we had lost the connection. Thankfully,about 60 seconds later, we heard Satoshi’s voice again as contact was restored.

The rest of the eventwent flawlessly and all 12 students received answers to their well thought-outquestions. At 11:23 EDT, the connection dropped as the station continued on itspath out of the range for Argentinean communication. The room erupted in applauseas this historic contact successfully completed.

As the forumcontinued over the next few days, news of the event captivated the populace asit was broadcast across the region’s airwaves. During the course of the week, Ialso had an opportunity to meet with students to talk about their dreams of careersin engineering and science. Student after student told me how inspirationalthose moments were when we made contact with the station crew. A boy namedSharaz, who happened to be one of the 12 lucky students who spoke with thestation astronaut, expressed to me that being a part of the event was the bestmoment of his life; a moment he will never forget! Other students communicatedthat they knew anything was possible for their lives now, because of thisexperience.

It can be a challengehere in International Space Station Program Science Office to measure theeffectiveness of programs that we implement. As we work with educators to designactivities, our goal is to motivate the next generation of scientists, thinkers,innovators and explorers. What I found, based on my experience with theCaribbean ham radio contact, is that our work is not only meeting objectives, inspiringfor generations to come!

Camille Alleyne

(Credit: Jackie Hicks)

Camille Alleyne is an Assistant ProgramScientist for the International Space Station Program Science Office with NASA’sJohnson Space Center where she is responsible for leading the areas of communicationsand education. Prior to this, she served as the Deputy Manager for the OrionCrew and Service Module Test and Verification program. She holds a Bachelor of Science degree inMechanical Engineering from Howard University, a Master of Science degree inMechanical Engineering (Composite Materials) from Florida A&M Universityand a Master of Science degree in Aerospace Engineering (Hypersonics) fromUniversity of Maryland. She is currently working on her Doctorate in ScienceEducation at the University of Houston.