In today’s A Lab Aloft, International Space Station Chief Scientist Julie Robinson, Ph.D., discusses the top research results from space station science in 2015.

Now that utilization of the orbiting laboratory is in full swing, more and more advances in science are coming out of research conducted aboard the International Space Station than ever before. With close to 500 investigations on-going, the space station continues to be not only a test bed for research that will help us travel further into space, but also continues to provide results that benefit humanity back on Earth. You probably know that this year saw the start of the historic One Year Mission and Twins Study, which will provide critical data and understanding for future missions to deep space. It also marked the first time lettuce has been grown and consumed in space, and we celebrated 15 years of continuous human presence aboard the only microgravity laboratory in the universe. What you may not know are some of the top results that came out in the past year, based on research on the International Space Station. These are my personal top picks.

Hope Crystallizes

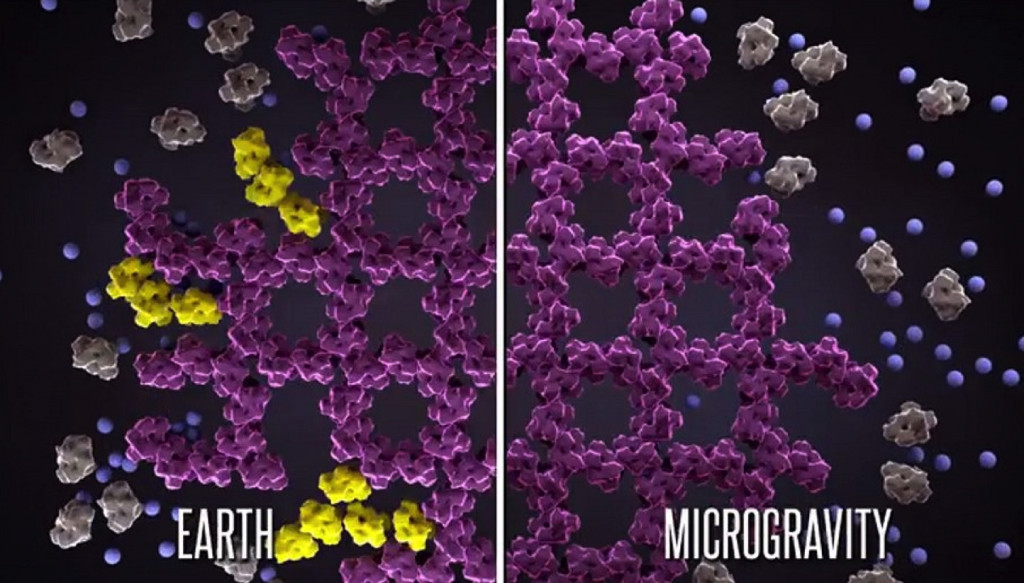

Clinical trials of a new drug for treating Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) called TAS-205 have begun sponsored by Taiho Pharmaceutical (see the entry in clinicaltrials.gov). This drug was developed using improved structures of key proteins that were crystallized on the ISS. The microgravity environment supported growth of larger, higher-quality crystals. This allowed scientists to design a drug to fit specifically into a location on the protein associated with DMD. Based on ground research in animals with a similar genetic disease, the research team estimates that the drug may be able to slow the progression of DMD, an incurable genetic disorder that affects the muscles primarily in young males, by half.

For me, starting clinical trials is a real milestone for this ISS research. There are so many things that can stop a science result from making it to a new drug, but once it makes it to clinical trials, data and not fundraising will have the greatest influence.

First genetic results investigate a link between folate and eye health in space

Damage to vision has become one of the top medical concerns of long-duration spaceflight, with increased pressure in the head due to fluid shifting in the body as a top suspect cause. A real puzzle has been why this only occurs in some astronauts, but not all. In 2015, scientists identified two polymorphisms (versions of genes that are slightly different in different people) present in astronauts who experienced vision impacts in space.. In the prestigious Journal of the of American Societies for Experimental Biology paper, researchers describe the polymorphisms are in genes that are part of a metabolic pathway called 1C that also uses B vitamins. In affected individuals, there could be a link between vitamin status and eye health

This was the first time that NASA has ever looked at genetic data from a group of astronauts. What really surprised me is that the One-Carbon Metabolism Pathway associated with folate and DNA synthesis could be correlated with what scientists have been viewing as a pressure disruption from fluid shifts in the brain. And the really surprising thing is that there are similarities between astronaut data and women who have infertility from polycystic ovarian syndrome. These kinds of surprises are the places where new advances come from, and I can’t wait to see the next piece of evidence in the puzzle.

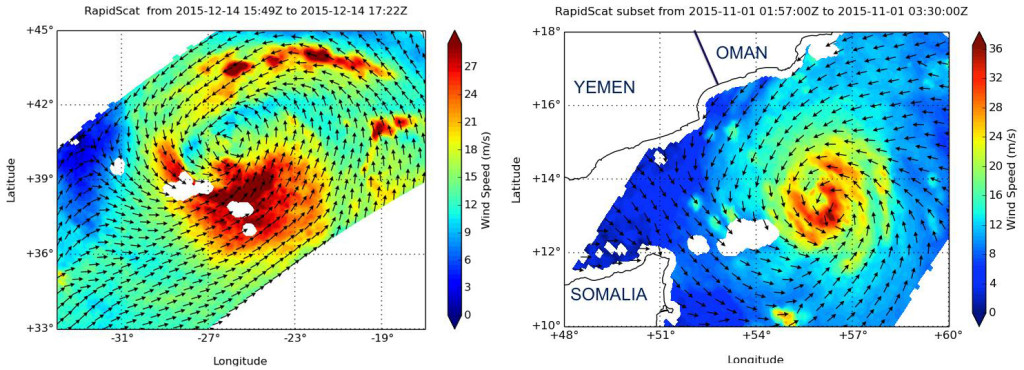

Better weather warnings help reduce risks

Though the ISS-RapidScat has only been aboard the space station for a little more than a year, its weather observations have already made a difference in reducing risks for humans back on Earth. In 2015, data from the RapidScat instrument on the station improved tracking of hurricane strength prior to and during landfall, and enabled better storm warnings to reduce risk to shipping and coastal populations. RapidScat is the first near-global scientific Earth-observing climate instrument specifically designed and developed to operate from the exterior of the space station. The instrument measures near-surface ocean wind speed and direction, and provides data that is used to support weather and marine forecasting, including tracking storms and hurricanes.

NOAA uses the RapidScat data in their hurricane forecasting. There may not be a NASA logo sitting alongside the NOAA logo. As a resident of Houston, I have a personal understanding of the risks of not preparing for a hurricane as well as the risks of evacuation. Good forecasts are critical to saving lives. I am really glad to know the ISS-Rapidscat instrument is doing its part to make those predictions more accurate.

Surprising results from the Constrained Vapor Bubble investigation

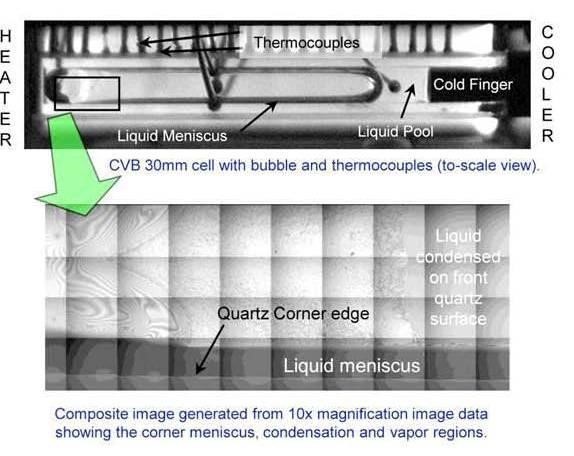

A heat pipe is a system for transferring heat away from a source using thermal transfer and phase change between liquid and gas. They are great options in space because they don’t have moving parts like pumps, and they are also used in electronic devices so they won’t have to have fans or pumps. Joel Plawsky of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: The Constrained Vapor Bubble experiment took a simplified heat pipe into space to measure its performance without the complexities of the bubbles rising due to gravity (buoyancy driven convection). Operation in the microgravity environment provided a number of surprises.One was rapid controlled boiling (they call this “explosive nucleation”!) in the shortest CVB module. Another was that the discovery normal capillary-driven flow of liquid from the cold to the hot end of heat pipe collided with a backward flow of liquid from the hot end toward the cold end due to Marangoni convection. The Marangoni flow also occurs on Earth but is very, very difficult to observe due to the action of gravity. I have to admit I learned a lot about heat pipes from reading this paper and then talking to some experts to better understand how they work. There will be more studies to come—but that collision is a source of inefficiency. This is an exciting and surprising result to me because once the physics are better understood, it can be applied to make smaller and more efficient heat pipes everywhere, including in this hot laptop I am using right now.

NASA’s International Space Station Chief Scientist Julie Robinson, Ph.D. (NASA)

Julie A. Robinson, Ph.D., is NASA’s International Space Station Chief Scientist, representing all space station research and scientific disciplines. Robinson provides recommendations regarding research on the space station to NASA Headquarters. Her background is interdisciplinary in the physical and biological sciences. Robinson’s professional experience includes research activities in a variety of fields, such as virology, analytical chemistry, genetics, statistics, field biology, and remote sensing. She has authored more than 50 scientific publications and earned a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry and a Bachelor of Science in Biology from Utah State University, as well as a Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology from the University of Nevada Reno.