In many popular movies scientists are cold, analytical men and women who run almost exclusively on the left side of their brains. Often, scientists and engineers are considered loners and the successful ones do not make mistakes.

I believe that such perceptions are not only dead wrong, but also discouraging to those who are thinking about their futures. “Who wants to work alone? Who is good enough to enter careers where perfection is needed? Not sure – but certainly not me!”

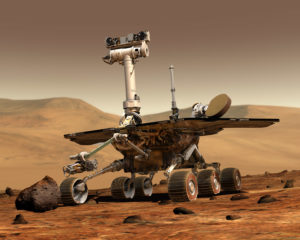

I spent this week, in part, at JPL bidding adieu to NASA’s Opportunity, which – together with Spirit – formed the Mars Exploration Rover mission. This mission started at the edge of disaster: JPL has two Mars mission failures in a row, putting its very existence at risk.

The Mars Exploration Mission was an attempt of a turn-around, a 3 year crash program targeted at re-establishing excellence. Lead by Pete Theisinger, a space legend and manager, and Steve Squyres, a youthful Cornell Prof and science lead, an exploration team was assembled.

It was a huge success when first Spirit and weeks later Opportunity responded from the surface of the Red Planet. The missions, initially designed to last 90 days each and good for 1 km of driving, exceeded their mark manyfold. Opportunity drove longer than a marathon and lasted over 55 times longer than designed. And these missions changed entirely how we think about Mars now.

By any measure, this exploration team is one of the very best and most successful. Yet, if you try to find the stereotypical engineers and scientists I described earlier, you will be disappointed.

Many remember the pure joy and elation at the beginning of the mission. The team members were deeply passionate and excellent during this mission. They decided to forego the proprietary phase of their schedule and directly released the data that came down from Mars – to the elation of millions worldwide. Joy, inspiration and love were words heard in pretty much any science meeting focused on this.

But, what struck me is how the end of the mission felt.

The team was prepared: Spirit was lost years ago, and Opportunity had been silent for 8 months due to a dust storm, even though the team sent over 1000 commands to wake it back up. It was my job to decide when it was over. We pulled the team into a room on Tuesday and told them that we would try one more time and – if not successful – I would declare the mission complete on Wednesday.

This session felt like a memorial to a loved family member. Tears were flowing freely as scientists and leaders shared their memories and told each other how much they loved being part of this team – with two robotic emissaries on Mars.

Men and women of all ages talked about their passion, their worries they they would lose contact with the team that became family to them. They reminded each other of challenges, near-death experiences their missions overcame – by them working together. They were vulnerable, often dissolved in tears, and visibly touched, but deeply proud.

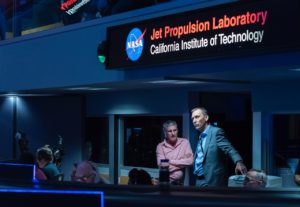

Many team members came to the command center in the evening. Squyres chose the last wake up song – Billie Holiday’s “I’ll be seeing you”. The team was there and talked about common experiences, about love – the raw emotion of individuals who put their heart and soul into something that gives purpose and a sense of community. The picture below shows Steve and I in the ops center as the final commands are sent out.

No, these are not left-brained analysts who work alone. I am sure there are introverts and extroverts, but they work together, passionately.

Great, history-making science of the type we do at NASA is a team sport, a deeply emotional affair. Exploration is about individuals with mistakes and deficiencies coming together and struggling, transcending their limitations to create something that is as close to perfection as it can be.

I wish we could explain that to children and to their parents.